Art by John Gerrard Keulemans.

Art by John Gerrard Keulemans.

When English sailors landed on the treeless shores of the Falkland Islands in 1690, they didn’t expect to be greeted by a wolf. Yet there it was: bushy-tailed, golden-eyed, and utterly unafraid. It padded right up to the crew of Captain John Strong, sniffed their boots, and snatched their food with the confidence of a camp dog. It wasn’t fierce, nor was it wild in the way they expected wild animals to be. And this would bring its demise, like it did the Dodo bird.

The creature they met was the warrah — Dusicyon australis — a canid found nowhere else except this island. Also called the Falkland wolf, the warrah looked like a ghost fox wandering out of a fairy tale. Two centuries later, it would vanish entirely. Shot, poisoned, and betrayed by the very trait that had helped it survive in splendid isolation: its friendliness.

The ghost wolf of the Falklands meets Darwin

Before Europeans ever set foot on the Falklands off the coast of Argentina, the warrah owned the place. It was the only native land mammal on the archipelago, a solitary predator trotting the rocky coasts and tussac grasslands.

It wasn’t big, somewhere between a golden retriever and a corgi. When French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville saw it in the 1760s, he couldn’t quite make up his mind: wolf or fox? He settled on loup-renard — “wolf-fox.” Almost no one really gave this animal much thought until Charles Darwin came along.

In 1833, during the voyage of the HMS Beagle, Charles Darwin found himself face-to-snout with the animal. He recognized it immediately as an oddity. How had a land predator ended up on an island hundreds of kilometers from the mainland, and why was it so tame?

“The only quadruped native to the island, is a large wolf-like fox, which is common to both East and West Falkland. Have no doubt it is a peculiar species, and confined to this archipelago; because many sealers, Gauchos, and Indians, who have visited these islands, all maintain that no such animal is found in any part of South America,” Darwin wrote

The first question was more difficult to answer, but the second one was approachable.

The Falklands are a bird-rich ecosystem. No one threatened the warrah. Humans called it Dusicyon almost mockingly, as in Greek, it literally translates to “foolish dog”. But the warrah wasn’t foolish; it was adapted to centuries of life on the island.

Sailors were amused at how easy it was to kill the warrah. The animal would simply come and scour around humans, showing no fear. People would simply walk up to it and stab it, or bait and kill it

“The Gauchos, also, have frequently killed them in the evening, by holding out a piece of meat in one hand, and in the other a knife ready to stick them,” Darwin wrote.

Darwin then proclaimed the warrah would soon go extinct.

“Within a very few years after these islands shall have become regularly settled, in all probability this fox will be classed with the dodo, as an animal which has perished from the face of the earth.”

The first known canid to go extinct

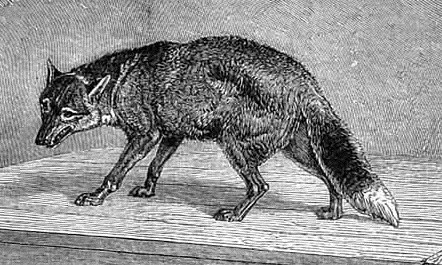

A lone warrah reached London. This illustration is from a 1873 Illustrated London News.

A lone warrah reached London. This illustration is from a 1873 Illustrated London News.

For the most part, the warrah was little more than a curiosity. But as settlers poured in — many of them Scottish farmers — the warrah became a problem. It was blamed for killing sheep, although the truth may be murkier. In panic, sheep often ran into bogs and drowned. But perception matters. The warrah was labeled a menace. Bounties were placed on its head.

Fur traders joined in. In 1839, the American Fur Company sent ships specifically to harvest warrah pelts.

The killing was easy. The warrah didn’t run. Hundreds or thousands of years of evolution couldn’t be undone so quickly. It was hunted to extinction with ease. By 1865, it had vanished from East Falkland. A last breeding pair was shipped to the London Zoo, but it was an insufficient attempt. Only one survived the journey. It died without reproducing in London, far away from its home off the South American coast and any biological relatives.

In 1876, the last known warrah was shot on West Falkland. Just 43 years after Darwin predicted its extinction, it was gone.

Only about a dozen Falkland wolf specimens survive in museum collections today. One of them was shot by Darwin himself. Its fur lies flat under glass. Its glass eyes, unseeing.

For billions of years, evolution had its own way of doing things. Then, humans came and unraveled that.

The Falkland wolf was sometimes hunted for its fur.

The Falkland wolf was sometimes hunted for its fur.

Island species evolve in isolation, often shedding the instincts that once protected them and developing useful habits. When outsiders arrive (whether it’s humans, livestock, or invasive species ), they’re defenseless. The warrah went extinct in no time, as did the dodo, the Great Auk, the Pinta Island Tortoise, and the Stephens Island Wren, which was decimated by a single cat.

These animals (and many more) have become colonial expansions or sad footnotes in the notebooks of naturalists like Darwin.

Researchers can’t bring the warrah back. But they can at least understand its story. In 2009, a genetic analysis of museum specimens showed that the warrah’s closest living relative wasn’t another fox or jackal, but the maned wolf, a long-legged canid of South American grasslands. In 2013, another study zoomed in on a different species: Dusicyon avus, an extinct mainland canid that lived in Patagonia until just a few hundred years ago. When researchers compared the warrah’s DNA to this vanished cousin, everything clicked. The warrah wasn’t a distant offshoot from millions of years ago — it had split from D. avus just 16,000 years ago, right at the peak of the last ice age.

During the Last Glacial Maximum, sea levels had dropped by over 100 meters. The strait between Patagonia and the Falklands narrowed to just 20 or 30 kilometers — and likely froze over. The warrah, or its ancestor, may have simply walked across. Or it may have swam or undertaken a grueling journey.

In 2021, a team of archaeologists working on New Island in the western Falklands unearthed startling clues: sudden spikes in charcoal, middens of penguin bones, and a stone projectile point — all dating to between 1275 and 1420 AD. This was centuries before Europeans set foot on the islands.

In other words, people had been here before.

These weren’t settlers, but they came, likely in boats, and they hunted. That suggested an alternate theory that the warrah reached the Falklands alongside humans. They may have been pets or hunting companions, which would explain why they were so friendly to humans.

The warrah’s tameness, long assumed to be the product of island evolution, could have older roots. Maybe it wasn’t tame because it had never seen a predator — but because it had always known humans.

We don’t fully understand how warrahs began in the Falklands, but we know how they ended.

The feeble bark of the warrah, silenced forever in 1876, is a deep echo of the Anthropocene. It’s a reminder of what is lost when human expansion proceeds without understanding or compassion. And it is a somber reminder of the irretrievable price of ecological ignorance.