Four years ago, 24-year-old New Zealand track cyclist and one-time Olympian Olivia Podmore died tragically, in the wake of professional and personal struggles. Today, 1News Sports Editor Abby Wilson looks back on her friendship with the frank, funny and effervescent “Liv”. A friendship that began in 2018 when Wilson first met with Podmore to talk about concerning rumours around the culture at Cycling New Zealand. A coroner’s inquest into Podmore’s suicide concluded in April. Its report is yet to be released.

Not many of my stories keep me up at night. That’s probably not surprising for a sports reporter, a line of work where there are winners and losers, but nobody dies.

That was before Olivia Rose Podmore. She was 24. When I got the phone call from a colleague on August 9, 2021, I sank to my knees on the floor of my bedroom. I was adamant there’d been a mistake. “No she can’t be. She’s in Queenstown. She messaged me over the weekend.”

But I was wrong, Olivia – Liv – was gone.

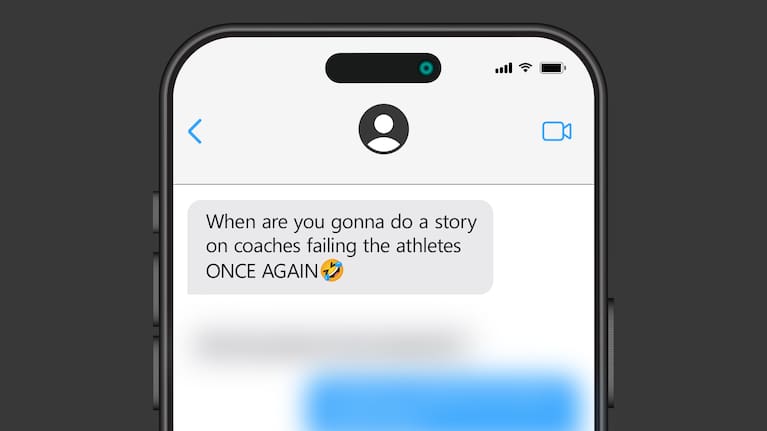

Just two days earlier I’d received a message from the Olympic cyclist.

“When are you gonna do a story on coaches failing the athletes ONCE AGAIN”

You see, while a journalist should never reveal their sources, I don’t think Liv would mind me telling you that she was one of mine. One of the bravest, strongest ones I’ve encountered.

It all started on May 30, 2018. Cycling New Zealand coach Anthony Peden had resigned and I was on my way to Cambridge, the home of the organisation’s high-performance programme, to do what I thought would be a straightforward story for the evening news. It turned out to be just the beginning.

Over the next few days I learned of and exposed allegations of inappropriate behaviour, bullying, breaches of confidentiality and a relationship between a rider and a coach, all within the Cycling New Zealand programme. The following week Sport New Zealand announced a full review.

Finding people to go on the record and talk about the issues was tricky, even harder was convincing anyone to talk on camera. But three days later I was back in Cambridge, my cameraman waiting in a car outside a house, while I sat inside, having a cup of tea in the kitchen with two women. One was someone very close to the programme but not a cyclist, the other was Liv, who I’d previously only met inside a velodrome.

Liv was 22 years old and surprisingly poised, when you consider I was a TV journalist filing stories about the organisation she worked for. The organisation that controlled her current life as well as her hopes, dreams and future Olympic aspirations. Many would have been cagey and nervous, but Liv was calm and thoughtful in her responses to my questions. Measured beyond her years. I was struck by how her she maintained a smile, even as she recounted disturbing revelations about life in the programme.

Two years earlier she’d unwittingly uncovered an inappropriate athlete-coach relationship at a pre-Olyympic training camp in Bordeaux, but rather than action being taken against those in the wrong, Liv felt she was the one being punished. And now, with the situation seemingly worse rather than better, she was desperate to find a fix, one that maybe I could help with.

Bullying ‘difficult to comprehend’

A coroner’s inquest into Olivia Podmore’s suicide began in November 2024 and concluded in Christchurch in April this year. Though the coroner’s findings are still pending, the exhaustive inquest helped fill in details of just how bad things had become inside the Cycling New Zealand Programme.

Stories of how Liv was treated were recounted by witnesses, like how she was told not to “f**king crash” by her coach as she prepared to make her Olympic debut in Rio in 2016 as a 19 year old. Text messages were read aloud from the coach in question, some referred to her body and her sex life; other messages from teammates were threats, telling her to keep her mouth shut, or else.

In court, Liv’s father’s lawyer Hamish Evans called the extent of the bullying “difficult to comprehend”. He added, “that she lasted as long as she did… was a testament to her courage”.

Liv was courageous. Looking back now I think that came from her focus on the change she wanted to see. This wasn’t about telling on people to get them in trouble, this was about a programme that was broken, a programme that Liv very much wanted a future in, a programme that she was prepared to stick her neck out to help improve.

I never did invite my cameraman in that day at the house in Cambridge. I was terrified of getting Liv in trouble and determined to keep her public involvement in the story to a minimum. Remember, if she wanted to ride her bike wearing the fern, being a part of Cycling New Zealand was her only option. I couldn’t ruin it for her.

But Liv was less cautious. In typical “don’t-give-a-shit” fashion she added me on Facebook, a public connection that surely didn’t go unnoticed by those involved with the programme. We traded messages from that point on, sometimes updates of our lives, other times fact-checking around stories and developments.

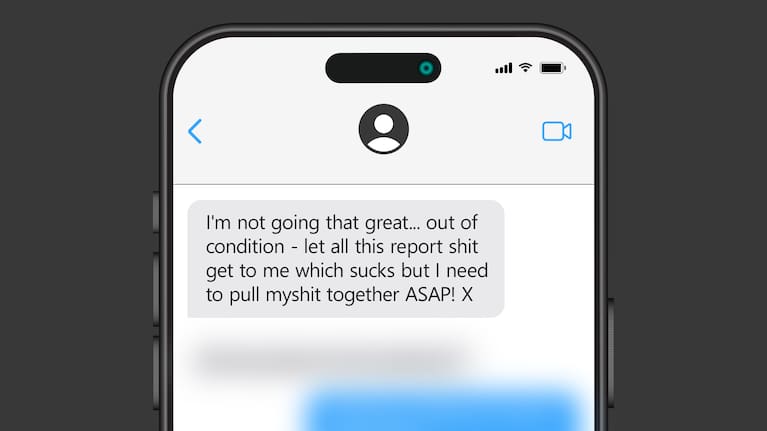

In late September 2018, she confided that she “wasn’t going that great” on the bike, which she felt was due to the stress of the report.

At this stage Liv had been interviewed by Michael Heron KC who was leading Sport New Zealand’s formal review into Cycling New Zealand. By all accounts she’d poured out her heart and soul in the interview. She trusted the process. However, with the report’s release date drawing closer, she was worried.

But, as I would come to see was a common theme with Liv, she didn’t let the worry linger, pulling herself into line with: “I need to pull my shit together ASAP!” Then another text: “Stay groovy”

Even reading that now makes me smile. I can imagine her goofy grin as she wrote it.

‘It’s all good, I got this’

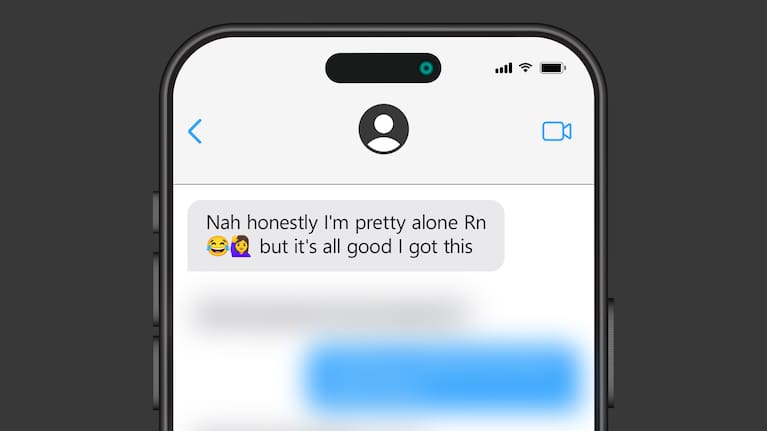

The truth was that the relationship between Liv and her teammate, the rider she’d exposed as having an inappropriate relationship with the coach, was bad. Liv was trying to train and compete with an athlete who she found was “refusing to talk, look at me or be in a room alone with me”.

“I’m done” she texted me. “Honestly I’m pretty alone Rn [right now] but it’s all good I got this”

That was a week out from the release of the Heron Report, a thorough investigation into the environment at Cycling New Zealand.

If things were bad for Liv at that point, they weren’t about to get any better. Her relationship with her fellow athlete was at breaking point, yet they were still expected to interact daily as they prepared for an international event.

But if Liv was feeling isolated and ostracised, it might have been invisible to some of those around her.

“I don’t even think the team realises how hostile it is” she texted. “Which is fair enough, it’s not their problem type thing!”

Liv was considering walking away. In hindsight many people probably wish she had. But her glass was half full. She could see a world where things would improve, she hoped the future was bright. She had an athlete’s drive and things she still wanted to achieve in her sport.

Incredibly, all this disruption was Liv’s backdrop for the Oceania Championships in Adelaide. Despite this, she showed up, she competed, she won a silver medal in the keirin. Two days later the Heron Report was released.

Watching the Tokyo Olympics from Cambridge

Fast forward nearly three years. Liv wasn’t where she thought she’d be. Instead of realising the culmination of years of hard work and competing at her second Olympics, in Tokyo, she was spending the winter in Cambridge, watching on TV while others blasted around the Izu Velodrome, living out her dream. During the qualification period Liv had helped to secure New Zealand a cycling quota spot for the Games but then she wasn’t personally selected for the team. It was a Cycling New Zealand decision she appealed, sure she deserved to be there, but her appeal was ultimately declined. The spot – her spot – instead given to an endurance rider.

To make things worse, the replacement rider didn’t perform well at the Olympics. Liv felt betrayed.

On that magical day in Tokyo, when our rowers won three medals in the space of an hour, we sent cameras to Cambridge to film Liv and other athletes cheering from a makeshift grandstand set up in her flat. Her hands were clapping, she was laughing and cheering but those of us who knew Liv could tell things weren’t right. Her contagious spark was missing. Off camera her emotions spilled over to our TVNZ reporter – she burst into tears. It was 10 days before her death.

A week later Liv was in Queenstown snowboarding – a getaway but seemingly not an escape. That was when she sent the text about “coaches failing athletes again”, and it was clear that, even on holiday, this is what was on her mind .

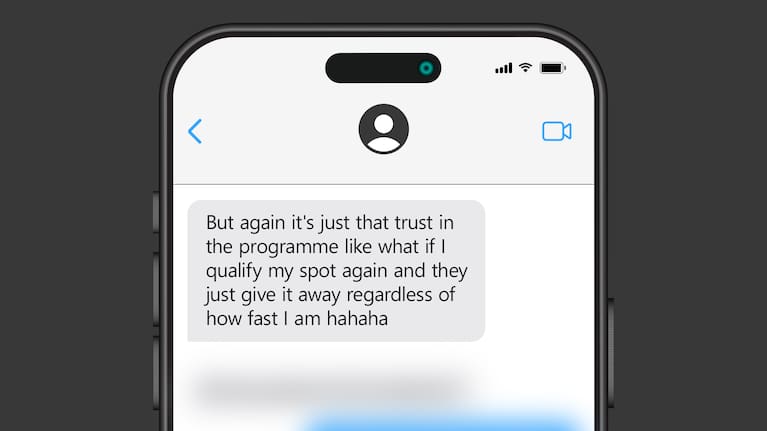

“it’s just that trust in the programme like what if I qualify my spot again and they just give it away regardless of how fast I am hahaha”

It wasn’t really funny. But that was Liv, sheath the knife in a joke. Hide the betrayal and the hurt.

The system said it had changed, Liv didn’t think so.

Forty-eight hours later Olympian #1333 posted to Instagram:

“Peace out”.