A majority of the justices on the Supreme Court of Nevada ruled on Monday that the NFL cannot compel former Las Vegas Raiders head coach Jon Gruden to arbitrate his claims accusing NFL commissioner Roger Goodell or someone on the commissioner’s behalf of tortiously interfering with his Raiders contract.

The decision affirms a 2022 ruling by Clark County (Nev.) District Court Judge Nancy Allf to deny the NFL’s motion to dismiss the case to an arbitration overseen by Goodell.

The decision also increases the odds the NFL will seek a financial settlement with Goodell before pretrial discovery could lead to invasive requests to the league and its officials for emails, texts and testimony.

At the same time, pretrial discovery could be problematic for Gruden, too. He would need to share emails, texts and other materials related to his current and previous viewpoints, as well as prior statements, concerning race, sexual orientation and other potentially controversial topics. A settlement might make sense for both sides.

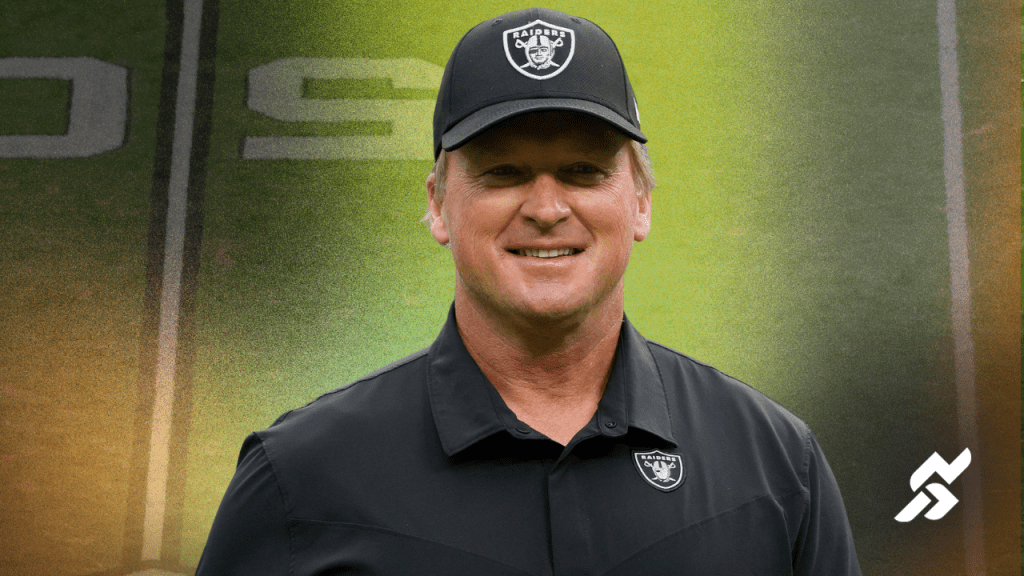

Gruden v. Goodell & NFL has roots in the ex-coach’s departure from the league four years ago.

In 2021, Gruden resigned from the Raiders in disgrace following stories from The New York Times and Wall Street Journal about emails he wrote when he was an ESPN employee in 2011. Gruden’s emails were sent to then-Washington Commanders president Bruce Allen and contained racist, misogynistic, transphobic and homophobic statements. By resigning, Gruden forfeited about $60 million on his Raiders contract. He also lost endorsement deals and saw his reputation as a Super Bowl winning coach damaged, perhaps irreversibly.

Even though Gruden wrote the offensive emails, he contends the NFL—and Goodell—broke the law. His lawsuit contains claims for tortious interference with his employment contract, negligence and civil conspiracy. The emails might have been obtained by the league in its investigation of then-Washington owner Dan Snyder, though that has not been proven.

The NFL and Goodell flatly deny Gruden’s allegations and—most importantly in Monday’s ruling—maintain that a court shouldn’t review the case. Through his Raiders employment contract, Gruden contractually accepted an arbitration process outlined in the league constitution.

Allf wasn’t persuaded to toss Gruden’s case to arbitration despite his contractual affirmation. She was receptive to Gruden’s point that he wasn’t provided a copy of the league’s constitution, and thus (arguably) he never consented to its terms. Allf also found Gruden’s contention that since he was no longer a coach of an NFL team, he can’t be bound by an arbitration provision that contemplates NFL authority, to be a salient factor in the legal analysis. In addition, she thought the arbitration provision was unenforceable on account of it being, in her view, unconscionable.

Last year, Justices Elissa Cadish and Kristina Pickering rejected that line of thinking and agreed with the NFL that Gruden’s case must be dismissed to arbitration. They emphasized that Gruden contractually assented to a statement saying he acknowledged having “read the NFL Constitution and By-Laws and applicable NFL rules and regulations, and understands their meaning.” Cadish and Pickering also reasoned that “arbitration clauses are presumed to survive contract termination” when the dispute is about facts and occurrences that took place during employment.

Gruden then successfully petitioned the Supreme Court of Nevada to accept an en banc reconsideration, meaning a review by seven justices.

Monday’s majority opinion was authored by five justices: Chief Justice Douglas Herndon and Justices Ron D. Parraguirre, Linda Marie Bell, Lidia S. Stiglich and Patricia Lee.

The majority reasoned that Gruden, as a former employee, “is not bound by the arbitration clause in the NFL constitution.” The majority worried that if the constitution were to bind former employees, Goodell “could essentially pick and choose which disputes to arbitrate.”

The five justices also concurred with Allf that the arbitration clause in the league constitution was unconscionable. They reasoned the clause is a contract of adhesion, meaning one in a take-it-or-leave-it form.

While the majority acknowledged that Gruden “could have” negotiated his employment contract, they wrote “the same does not apply to the NFL constitution.” To that point, the five justices underscored that Gruden couldn’t negotiate a change to the league constitution, which is a legal document governing the relationship between the league and teams. He also couldn’t demand it not be incorporated into his employment contract.

The majority’s unconscionability analysis also took aim at Goodell’s role in finding the arbitration clause “substantively unconscionable.” The five justices stressed that the clause problematically authorizes “Goodell, as Commissioner, to arbitrate disputes about his own conduct—exactly what is at issue here.” The majority asserted the “ability of the stronger party”—such as the NFL compared to Gruden—”to select a biased arbitrator is unconscionable.”

The second way in which the arbitration clause is substantively unconscionable in the eyes of the majority is that the NFL can amend it “at any time, and without notice.” This is because the NFL (and owners) control the league constitution. In other words, Gruden could agree to arbitration language that could later be altered without his input or consent and still bind him.

In a dissent by Justices Pickering and Cadish—who previously ruled for the NFL—the duo reasoned the majority overlooks a basic fact: Jon Gruden, an educated adult, explicitly agreed to the employment contract and all its terms, and he also “expressly acknowledged that he had read the NFL Constitution, understood its terms, and agreed to its incorporation by reference into the contract.”

The two dissenting justices also pointed out case precedent indicating that judges should favor the compelling of arbitration. In addition, Pickering and Cadish stressed that while the majority decided the arbitration clause can’t apply to former employees, the clause itself doesn’t make such a distinction. The two justices suggest the five majority justices read language into the contract that wasn’t actually in the contract.

Pickering and Cadish also disputed the majority’s finding of unconscionability. They underscored that even if Gruden thought Goodell—who Pickering and Cadish thought probably wouldn’t serve as arbitrator—was biased, Gruden could petition a court for review of the award on grounds of arbitrator bias.

The NFL declined a request for comment.

To be clear, Gruden hasn’t won the case. He still must prove his factual allegations and establish that his legal theory works. But Monday’s ruling gives him more leverage, especially in settlement talks.

The ruling also comes as Minnesota Vikings defensive coordinator Brian Flores continues a lawsuit in the Southern District of New York (SDNY) against the NFL and several teams for racial discrimination and retaliation. Much of his case has been dismissed to arbitration. A ruling by the Supreme Court of Nevada is not binding on the SDNY or the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, which has jurisdiction over the SDNY and which famously ruled that Tom Brady’s Deflategate case could be decided by an arbitration process overseen by Goodell. Nonetheless, expect Flores’ attorneys to reference Gruden’s appellate victory in future filings.