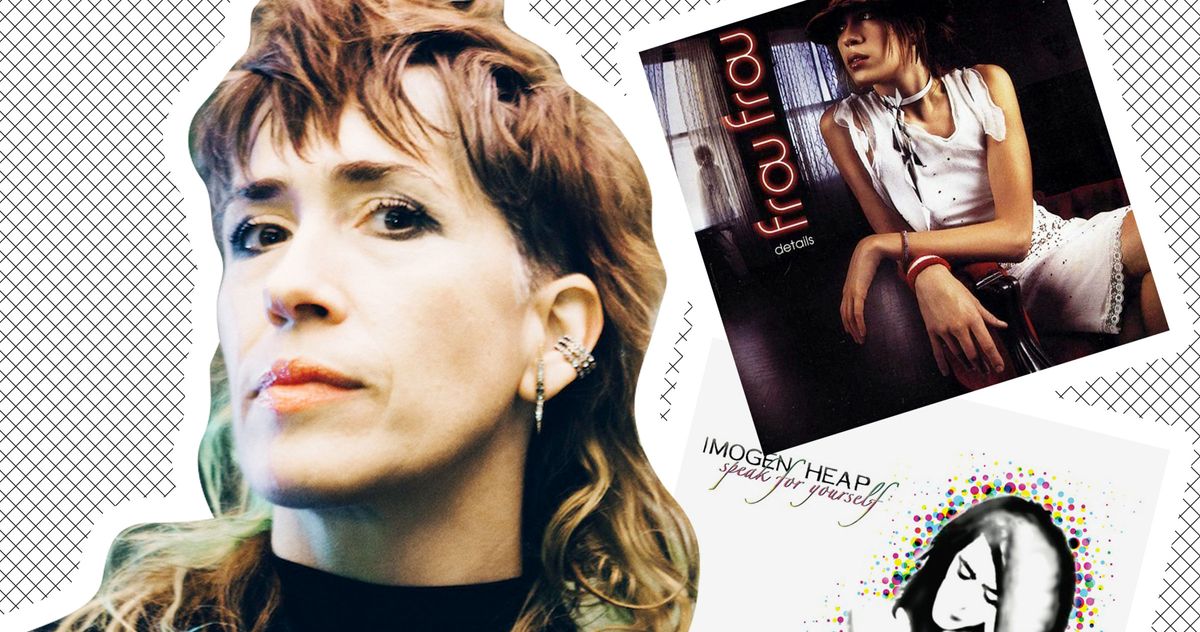

Photo-Illustration: by The Cut; Photos: Fiona Garden, Retailers

When Imogen Heap set out to make her second album, Speak for Yourself, she was 27 and in over 10,000 pounds of credit-card debt. A classically trained prodigy who taught herself music production as a teen, she’d signed her first solo record deal at 18. A few years later, she joined forces with Björk producer Guy Sigsworth to form Frou-Frou, a dreamy electronic-pop duo that achieved moderate cultural prominence after their single “Let Go” appeared on the Garden State soundtrack. But their label dropped them after disappointing sales. Heap was left with no paycheck or institutional support. So she remortgaged her U.K. flat to fund the creation of Speak for Yourself, which she wrote, arranged, and recorded on her own. A rich tapestry of club beats, pop melodies, and production twinkles, the record is about the ecstatic possibilities of love and what can happen when you open yourself to the unknown.

Twenty years since its initial release, it is arguably more popular than ever. Heap has become one of the most quietly influential artists of the 21st century, an early “download diva” — as the Guardian called her at the time — resilient to the sea change from MP3s to streaming and short-form video. Her Speak for Yourself songs have soundtracked teen soap-opera episodes, SNL spoofs, and viral TikTok trends. Several generations of pop artists, from Taylor Swift and Ariana Grande to PinkPantheress, have cited Heap as a formative inspiration. Chatting with me from her home in Hackney, Heap says the reception of her work has been unexpected. “Back then, I didn’t know if anyone besides the people on the message boards would like anything I did,” she tells me. “It feels like the universe is constantly going, ‘Here you go.’”

Right now, Heap lives with her 10-year-old daughter, Scout; Scout’s father, her ex; and a Ukrainian videographer named Daria who fled Kyiv at the start of the war. Writing and recording music doesn’t interest her so much anymore; she says she’s turned down some high-profile requests for collaboration. “I’m just out of sorts with perfecting something that will later go into the noise,” Heap tells me. She is more interested in harnessing technology to facilitate creative expression through inventions like Mi.Mu gloves, which can generate music live (see her NPR Tiny Desk performance for a demonstration); an AI assistant named Mogen; and a I.P. and rights management program called Auracles that she hopes will give artists greater control over their work, including allowing them to opt out of AI training models. (A small army of assistants help Heap with these projects.) “In light of all the madness, I just want people to be identifying human work. How can we know that that’s a human author, and where can we see the threads, and where can we see the provenance?” she asks.

In October, Heap will release the 20th-anniversary edition of Speak for Yourself. Here, she reflects on its legacy, her current interests, and what she sees in the future.

When you listen to Speak for Yourself now, 20 years later, what stands out to you?

It’s just a feeling of me: how I was, what the world was like. I was trying to prove myself to such a degree that hardly anyone came in the studio for a whole year. I rented this studio in Bermondsey in an old carpet factory that used to be Dizzee Rascal’s. There was a hole in the window that finally cracked when I shut the window once. It was hard to stay motivated.

The biggest win was that I discovered my fans. I had a webmaster at the time, James Clarke, and he was like, “Look, I’ve got this website up about you, and there’s lots of fans chatting in there. Why don’t you tell them what you’re up to in the studio?” That’s how I got through the year. I would send them little snippets of ideas that I just couldn’t decide on, they would suggest things back, and I’d finish stuff knowing they’d always be there in the morning.

I liked my massive petticoats and huge stilettos and feather mohawks back then. But you know, as you get older, you don’t have time to spend half an hour on your mohawk every day. My style now is just dark, like cyberpunk. And I’m wearing jumpsuits because they’re easy and look cool.

What does your daughter, Scout, think of Speak for Yourself?

We haven’t sat down and listened to it all the way through. She did come on tour with me when she was 4 and 5, but she doesn’t remember it. It’s strange, like everyone is experiencing this person who made CDs back in the day. But the reality is mummy is creating weird tech projects with a bunch of people in the home.

One of the reasons Speak for Yourself resonates so much, I’d say, is that it has this giddiness and optimism toward love that seems almost unavailable now. What is your current attitude toward romance?

Twenty years ago, they didn’t have apps, so I did fall hopelessly in love with strangers and stare at people in coffee shops. But now I’m on the apps. In fact, my last video was partly funded by Feeld. Mostly, I’m window shopping — just looking and chatting and just interested in people’s kinks. Around five years ago, I had been largely kind of asexual. I discovered I had something called Hashimoto’s. When I changed my diet, my sex drive came back. It was crazy. That’s where some songs like “What Have You Done to Me?” and then “Noise” and “Aftercare” are from.

I’ve largely had boyfriends. But more recently, I’m just finding myself going to Pilates and looking at girls and going, I wonder what you’re like. That had never happened to me before, which has always been annoying because that’s half the planet that I’ve been ignoring. I’ve had some interesting dates, one with a trans woman and a trans man that were very enjoyable. And just like, made my brain go in all kinds of places that it’s never done before, and I myself am quite masculine. Men do comment on this and feel intimidated by it, but I can’t help it. I’m quite excited now. I’m no longer hetero. I call myself pansexual.

Welcome to the community!

I’m very much a relationship anarchist. Over the last five years, I just discovered all these things I didn’t know was a thing. I knew a few people that were poly, but it was just something that I thought was like over there, and weird, or not something that I could possibly get away with.

Yeah, how does that energy then filter back into the work?

I’ve just become more bold, and I don’t have expectations in the way that I had them. If you welcome every moment in the moment and meet it at face value, then everything just becomes so much more fun. Even with all the people that work on my team, if you don’t want to work nine to five, you don’t have to. Let’s think about how we could divide up this money differently.

You have a more active vision of the future and technology’s relationship to society than the average person. I’m curious to know whether there are thinkers who have helped shape your worldview.

They’ve just been people I have conversations with in the real world. In the music industry you’re so busy talking about yourself — and then you kind of go, Oh, wait, there’s scientists, environmentalists, all these other people. Time and time again, when you have a sense of something that’s missing, if you’re really open to letting things come your way, things will happen. That could be, “Oh, would you like to come to NASA Goddard Space Center?” And then two months later, “Do you want to come to MIT Media Lab and meet some people?” I’m ADHD, and I think that helps because you’re constantly starting things and then not stopping them.

I’m quite excited — one of my best friends, Rachel Millward, is running for deputy leader of the Green Party. Before she did that, I just thought of the Green Party as a bunch of eco-warriors. But Rachel’s super smart, and seeing her run for that makes me think that I could be the minister of culture, and maybe I could sort this and this out. I’ve been trying for the last ten years to redesign the art and IP space, because it doesn’t work. I just wish I were able to help more.

How has your assessment of both the possibilities and risks of AI evolved over time? You were one of the early musicians experimenting with it. Now we’re seeing these big tech corporations integrate AI into everything, and there’s been some conversation about AI’s impact on the water supply and pollution.

We’re in this soup right now, and there’s extreme wealth and huge egos that are just terrorizing us and our planet and our people. Everything is changing. But I have this emerging sense that if we are afraid, the only way to counteract that fear is to just get on with building the thing that you’re afraid of.

There are already huge amounts of AI-generated music being uploaded to DSPs. Once we’ve exhausted that, and we’re all bored of the same homogenous rubbish, then there is going to be an emergence of independent direct-to-fan technologies like AI agents.

I imagine I’m cooking in the kitchen, Scout has come back from school, maybe I’ve got some glasses on, and I’m making a piece of music because maybe there’s an AR overlay of things that makes me be able to play live drums or whatever. But then at the same time, maybe my friend Chris, in Brixton, can chuck some drums in. Then the fans can be like, “Oh, Imogen Heap is live. She’s on my app or on something else. Let’s go tune in.”

What is your relationship to social media and fandom these days? It seems like you’re mostly interfacing directly with fans through livestreams and things like that, and then maybe some outside chatter filters into your world.

I have been struggling. I loved it when it was my message board. But as you know, Twitter went mad, and there’s just so many more people now. For the last six years, I’ve been building the AI assistant Mogen. I’ve been chatting to my fans in this chair, hundreds of hours of conversation with feedback into Mogen, and which we will be launching in a couple of months on my app. I just hope that we can build things in time and that we don’t miss a generation of great music because artists are overwhelmed and can’t shout above the noise.

You mentioned it in one of your livestreams, but I was wondering what happened when you apparently liked a tweet about transgender people.

Apparently my Twitter account liked something that somebody else said in another tweet, and I can’t actually remember what exactly it said, but it was something about me liking something that said, “A man is a man and a woman is a woman, and there’s no there’s no two ways about it.” I didn’t like it, because I would never fucking like anything that said that. I feel deeply safe with the trans community, because they have questioned themselves. They have gone through so much trauma, and they’ve gone through so many things that most cisgender people have never done. Somebody caught this thing, took a screengrab of it, and then wrote their own story about it.

I just don’t fucking have time for people who do this bitchy stuff. It’s not because they made it sound like I wasn’t owning up to something. But I was like, No, I just don’t play that game.

Of the younger next-gen musicians who’ve cited you as an inspiration, who do you like to listen to?

I went to see Olivia Rodrigo the other day because Scout is massively into her, and I had the best time. She’s super good, for starters, she’s hilarious. She swore nonstop, but that’s okay. But I largely listen to music that isn’t lyrical. I like going out and listening to really dark techno, like standing by the bass bins and feeling the rush of air. I love Lorn. I’ve always liked Clarke — British electronica. One of my favorite people to see ever is this woman called Irene Amnes. She plays with modular equipment, and she is just a genius.

Any recommendations you’d like to leave us with?

I would go and see Hamlet Hail to the Thief at the Royal Shakespeare in Stratford-upon-Avon. It’s Hamlet Radiohead. I haven’t read it yet, but I’m pretty sure the book Raising AI should be read. If you’re worried about AI, you have a parenting role. And generally, I want to say the more disempowered we feel with our governments, the more scary and hopeless things feel — we feel like our communities are online largely, and that is hard space to deal with mental health. But I think it’s just really important to put your phone down, take a walk, and open up opportunities for the everyday in your real, physical life.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Stay in touch.

Get the Cut newsletter delivered daily

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice

Related