The El Rocco, a cellar on William Street in Sydney’s Kings Cross, started hiring jazz musicians because the TV they’d installed to get the punters in shut off at 10pm, and the young clientele drawn there by this novelty didn’t want to go home that early.

As jazz historian Bruce Johnson wrote, the El Rocco, which opened in 1955, wasn’t so much a venue as an entire era of Australian jazz unto itself. “The most daring thing you could do in the late 1950s,” writer-critic-broadcaster Clive James once said, “was to listen to Errol Buddle at the El Rocco”. Jazz bible DownBeat magazine called it one of the great jazz clubs of the world.

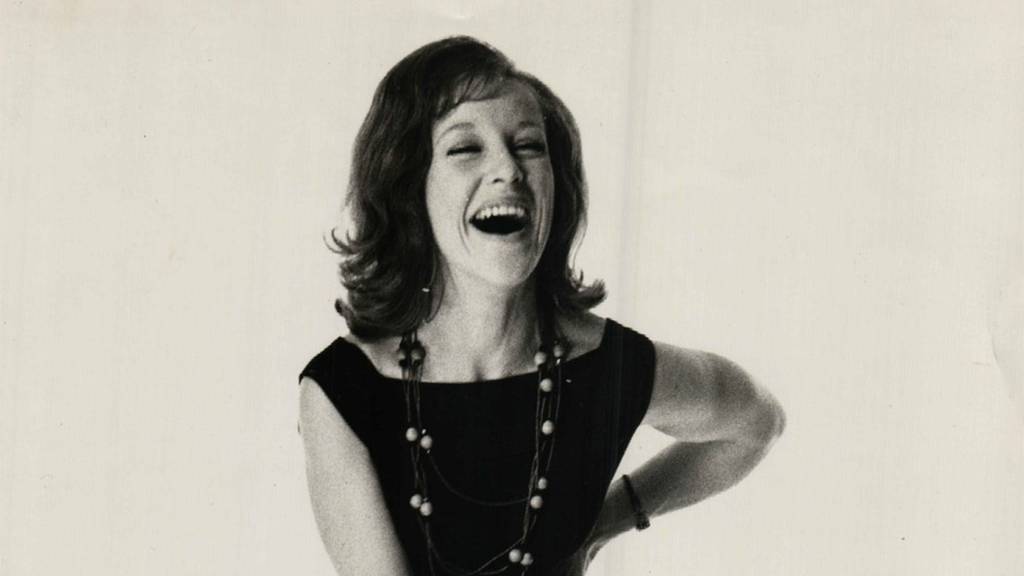

Judy Bailey, who died on August 8 at the age of 89, was one of the star performers at this club, and lived long enough to appear in a 7.30 item, speaking graciously and modestly about the hip hop artist’s sampling her 1970s work.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1209787

As a pianist, she had an effortless, flowing touch. Many jazz writers have noted that, like Thelonious Monk, piano is best appreciated unaccompanied by other instruments, although Bailey was a formidable band leader, as evidenced both on her early albums like My Favourite Things and the sprawling mid-70s jazz funk of Colours — the album which later pricked up the ears of various international hip hop producers. Indeed, I’m amazed it’s only “Colour of My Dreams” which keeps getting chopped up — the whole album is lousy with soulful vocal stabs and thick, heavy bass riffs.

Bailey started playing piano at the age of 10 and discovered jazz at 14, while “listening on a Bakelite radio to what I later learned was a test broadcast for a New Zealand station”.

Independent. Irreverent. In your inbox

Get the headlines they don’t want you to read. Sign up to Crikey’s free newsletters for fearless reporting, sharp analysis, and a touch of chaos

By continuing, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

“The tune was Lionel Hampton’s ‘East of the Sun’, which I’d heard in straight song form, and it was being played by the George Shearing Quintet,” she said in the early 90s. “I didn’t know that this was called jazz. It grabbed me. It was the fascination of trying to figure out how it worked. I’m still fascinated.”

There’s a faintly numinous quality to this story; the brain re-wired in an instant, new futures mapped out in synapses freshly ablaze. It was, among other things, the start of her interest in that crucial liberating innovation of jazz: improvisation.

“I instinctively knew that it was being invented as it happened, and I also instinctively knew that it was allowing these people to express their creativity.”

In a lecture on the subject in 1996 — by which stage she was also an educator of several decades — she theorised “that our earliest forebears, having discovered the use of their own particular, personal instrument, i.e. the voice, were then inspired and compelled to emulate the sounds they heard around them — the natural sounds of wind and water, birds and trees, animals and stones — an incredible variety of aural experience which could not be ignored and begged to be given expression in the soul of humanities — and so we witness the birth of improvisation, as an integral part of communication.”

When Bailey arrived in Australia at the age of 20, she was only supposed to be stopping by in Australia — six months here as a bridge between her Auckland home and the London scene. She ended up staying for the rest of her life.

She is one of a tangle of figures in this inexplicably half-forgotten world. Bailey played with bassoonist Errol Buddle, who had formed the Australian Jazz Quartet in the US and backed luminaries like Billie Holiday, Dave Brubeck and Helen Merrill. The band put out an eponymous LP of jazz standards in 1955, the cover four kangaroos against a burnt orange background. Bailey also shared the stage with Don Burrows, the first Australian jazz artist to earn a gold record, and John Sangster, who produced a sprawling series of albums dedicated to The Lord of the Rings from the mid-70s on.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1210274

Bailey, Burrows, Sangster and the great saxophonist Bernie McGann are captured on Columbia’s 1967 compilation, Jazz Australia. It should be commonplace — I should be sick of seeing it in record stores. But it’s out of print and has never been reissued.

Bailey, of course, did more than fine — she got steady work with television orchestras when that was a thing, taught as part of the first national jazz course at the Sydney Conservatorium from its inception in 1973, and recorded steadily — she was even on Play School.

But her passing is particularly melancholy because she was one of the last links to that world we had left — a world where brilliant musicians could earn a living in television orchestras and then spend their nights experimenting and developing for little pay at a place like the El Rocco, surrounded by artists and writers. A world where jazz was considered inherently seditious enough to attract police attention, even in a decidedly straight, booze-free joint like the El Rocco. Bailey long outlived that world, and most of the people she shared it with; everyone else featured on Jazz Australia, regular collaborators like Lyn Christie and John Pochee, as well as the other pioneering women of the El Rocco, Marie Francis and Molly Parkinson.

At the risk of repeating myself, eras like the El Rocco have been swept to the margins of Australia’s cultural memory, barely seeming to register in our idea of what’s creatively possible on this continent. On the other hand, there are people* who have kept it alive. I hope reissued LPs of Bailey’s ’60s work (original copies of which reportedly fetch four figures in Japan) are on their way, but you can find snatches of this world, so vividly of its era, online.

It’s all gone, but it’s all still there, and reflecting on Bailey’s life and work, particularly at the El Rocco, is an invitation to think about where similar creative centres might currently be, their new possibilities unfurling like ribbons of melody.

*A huge debt is owed to the website of Eric Myers, who has assiduously archived decades of great Australian jazz writing.