Australia’s offshore oil and gas industry has tonnes of steel, piles of fibreglass and massive quantities of contaminated polymerised plastic to deal with during the next 25 years, as its decommissioning work ramps up.

Soon, it may become a strange bedfellow for owners of renewable energy projects – if only to provide guidance on how not to handle retiring assets.

Offshore oil and gas decommissioning only ramped up after 2019, when the owner of the decrepit floating Northern Endeavour oil vessel in the Timor Sea became insolvent and the clean up became the federal government’s problem.

What followed were legislative changes to belatedly put responsibility back on the industry, a company levy to pay for the costs of decommissioning the Northern Endeavour, and a change in how the regulator National Offshore Petroleum Safety Authority (NOPSEMA) oversees retiring assets.

Now, it might provide a blueprint for how the wind, solar and battery industry also approach their challenges on dealing with the tricky-to-recycle materials, such as turbines blades.

“Essentially the impact (of Northern Endeavour) of that was to stimulate a lot of activity in the decommissioning space. The work was always going to happen but it took away some of the flexibility in timelines for the operators,” says Francis Norman, CEO of the Centre of Decommissioning Australia (CODA).

“Australia now is one of the busiest jurisdictions for decommissioning activity. And like the whole of the rest of the world, we are learning as we go.”

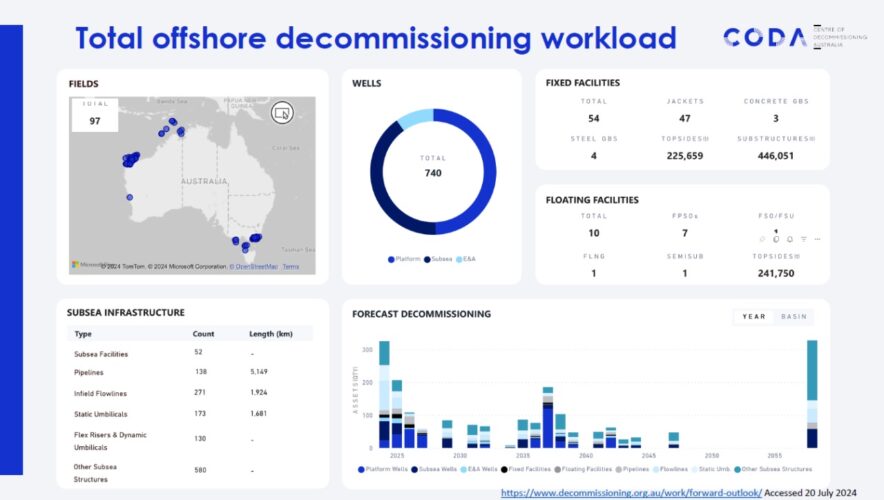

Norman says there are 740 offshore oil or gas wells that must be removed and the land around them rehabilitated between 2024 and 2050. CODA estimates that will cost $US40.5 billion ($A62 billion) over the next 50 years.

Image: Centre for Decommissioning Australia

In the renewables sector it’s the wind turbine blades that are the most prominent and most challenging to dispose of due to their sheer size, and their composite materials, and they are the hot decommissioning topic.

Wind decommissioning is being weaponised by astroturfing groups during planning processes, forcing first movers to refute weird claims such as turbine blades being buried in sand dunes (they will not).

Decommissioning in the oil and gas sector faces similar concerns to those being raised by groups that want to see renewables do better than the fossil fuel industry, says Rean Gilbert, a decommissioning expert with UK engineering firm Kent.

These cover recycling, material recovery, protections against insolvency and abandonment, and site restoration, which offshore is mandated by NOPSEMA and onshore is handled through landowner agreements.

The first “commercial” scale wind project to be decommissioned in Australia is Pacific Blue’s 18.2 megawatt (MW) Codrington; it had to deal with the sand dunes allegation earlier this year.

It must decide on how to bring down the towers, what to do with the fibreglass-and-polymer blades, and recycling the remaining infrastructure which includes concrete bases, cables and substations.

While Pacific Blue is starting from scratch in terms of setting up a playbook for wind farm decommissioning, the apparatus to handle the work is either already there or emerging, according to consultants working on the project.

Australia has the facilities and demand to recycle about 95 per cent of a turbine, said Everoze partner David Millar in May.

“There are [demolition contractors] looking to set up in Australia. They see the industry’s going to grow in decommissioning, and they want to be here to help run these projects and do it properly, so they’re ready and waiting,” he said during a conference in Melbourne.

“[And there are] contractors, saying we’d be interested to do an EPC contract on decommissioning, so actually take responsibility for the whole project including recycling.”

With five years of work already underway, a complementary offshore oil and gas decommissioning industry also holds potential for the wind industry, Norman says.

There is already an extensive industry establishing itself in Australia for recycling and handling materials used in the oil and gas industry.

This represents the non-landfill facilities available for recycling or otherwise handling decommissioned offshore oil and gas materials. Image: Centre for Decommissioning Australia

Furthermore, ports such as Bunbury in Western Australia (WA) could double as an offshore wind construction hub and a location for the biggest vessels required to transport heavy materials, such as pipes covered in marine life, from sea to shore.

Don’t be like oil and gas in the 70s

Calls for government and industry to set up a decommissioning framework for onshore renewable energy projects are getting louder.

A report by Re-Alliance this year found 1 gigawatt (GW) of solar, wind and battery assets will reach the end of their life within the next decade.

Being forced into a Northern Endeavour-like situation where the government must take control of a clean up, and charge the industry for it, is one good lesson for the renewables sector to heed.

“There’s a lot of similarities that we can learn from oil and gas that we can learn, the first one will be those end of life obligations, designing for decommissioning,” Gilbert told Renew Economy.

“When Australia originally put in the oil and gas assets 30 or 40 years ago, decommissioning wasn’t high on the list of priorities… We’re 1755360490 dealing with a lot of challenges where pipelines weren’t designed to be removed, so when they were put in 40 years ago in a trenched area and covered with 2 metres of rocks and sediment.

“Now we’re looking at it and thinking how do we remove it with the best environmental outcome.”

NOPSEMA’s targets are that all equipment will be entirely removed within five years of the start of decommissioning, with some negotiation allowed around pipelines.

Can they be trusted?

This week Greenpeace led a coalition of environmental groups and unions in a renewed call for the oil and gas industry to fund a single decommissioning hub in WA.

It’s not an idea that would be helpful for decommissioning onshore wind as projects which are spread across the country, nor would it be useful for the oil and gas industry which currently uses four ports in WA to handle a range of equipment and ships, says Norman.

“It’s a concept that has been floated for several years now,” he says.

But the coalition’s position doesn’t necessarily stem from a desire to see efficiencies, but from distrust that the industry will carry out required decommissioning, despite the threat of financial penalties from NOPSEMA.

While Pacific Blue is committing to handling the decommissioning of Codrington in a way that sets a high bar for industry best practice, it’s the oil and gas industry that is partly responsible for why Australians are worried in the first place.

Already major oil and gas companies Woodside and Santos are racking up decommissioning failures which led to a lawsuit, lodged this month by the Wilderness Society, against the latter over whether it will actually pay for the mandated decommissioning of a sub-sea pipeline.

NOPSEMA sent Woodside back to do clean-up work again after a series of preventable workplace safety incidents on the Stybarrow and Griffin fields in Western Australia, and the Minerva field in Victoria.

And Santos wells in the Legendre Field have been leaking gas into the ocean for a decade which it claims are “not technically feasible” to plug, and gas is also sleeping from 13 locations on the seabed near Santos facilities around Varanus Islands off the Pilbara coast, Boiling Cold reported in July.

Onshore, there are instances of oil wells on private land that have just been left and their foreign owner has disappeared overseas, leaving a landowner to deal with the mess, Gilbert says.

“Onshore oil and gas often attracts smaller companies. They’re not your Shells, Woodsides of the world that have a big presence, they’re tiny little companies you’ve never heard of but they get permission to drill a well on someone’s land. Then they go insolvent and you’ve got an orphan well,” Gilbert says.

“Orphaned wells are a big concern right now.”

Show me the money

The Wilderness Society’s lawsuit also comes from scepticism that Santos will come up with the cash to do the work on the Reindeer-1 field infrastructure, a fear that is top-of-mind for many landowners considering whether to host a solar or wind project.

Offshore oil and gas companies only have to budget for a worst case spill disaster, rather than what all of the infrastructure will cost to take down.

“Decommissioning one field could cost $1 billion. So maybe we shouldn’t be looking at spill response but the cost of decommissioning the entire field,” Gilbert says.

Having enough funding for decommissioning is a standard the emerging offshore wind industry is being held to from the beginning.

But for onshore renewables, mistrust in companies to do the right thing at the end of a project’s life is one of the pressing social licence issues the industry must address.

Farmer and tax lawyer Claire Booth neatly outlined the punchier attitude to non-farming industries leasing rural land, that partly emerged from the anti-coal seam gas movement Lock The Gate.

“Landowners should ensure that the [renewable energy development] company takes full responsibility for all operational risks … breaching of zoning or planning laws, and land rehabilitation at the end of the lease,” Booth said at the National Renewables in Agriculture Conference and Expo in Bendigo in July.

“And I don’t trust any f***er. If you are saying to me that you are going to be rehabilitating my farm in 20 years, where is the money? Who holds it, and how do I know that it’s not been put in a term deposit and wasted away?”

Rachel Williamson is a science and business journalist, who focuses on climate change-related health and environmental issues.