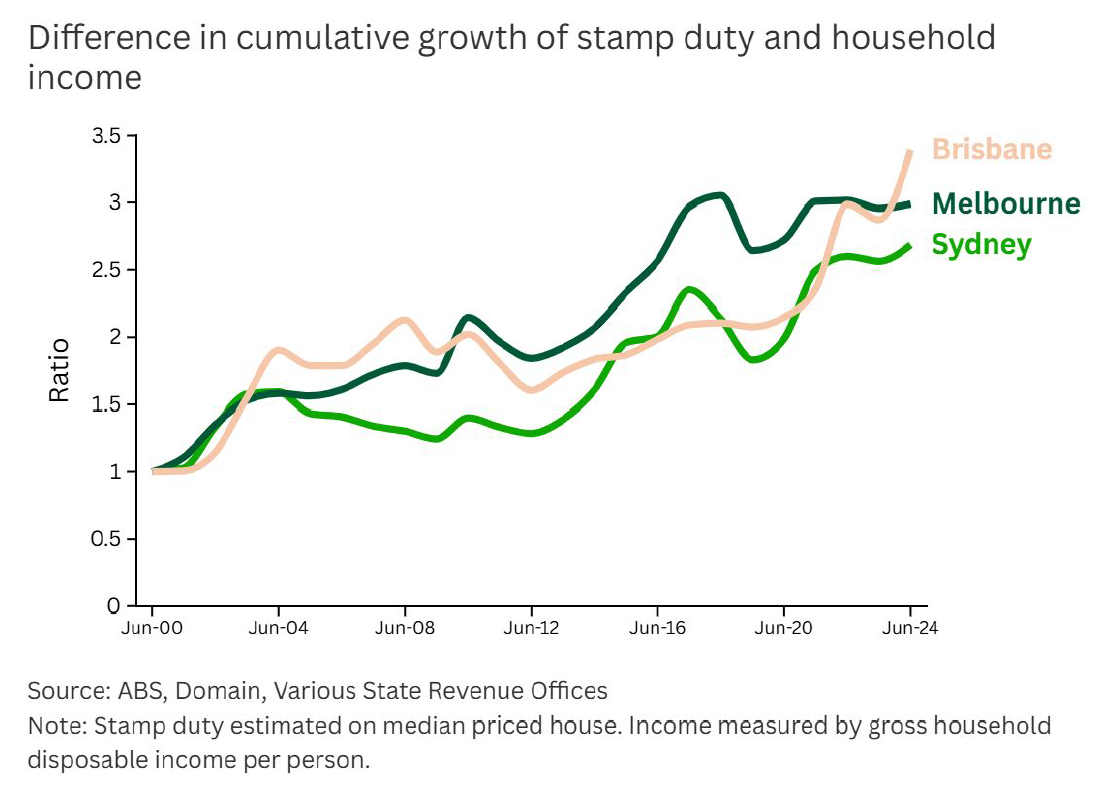

In Sydney, the stamp duty on a median-priced house has jumped from 45% of gross household disposable income per capita in 2000 to a staggering 120% in 2024. This shift has turned what was once a relatively manageable upfront expense into a significant barrier, forcing buyers to save for longer and pay more – on top of already steep deposits.

The analysis also underscores the far-reaching consequences of stamp duty, starting with the impact on individual buyers and rippling through to the broader economy and state finances. Powell said that stamp duty discourages people from moving for job opportunities or to homes that better suit their needs, and even deters about 25% of potential downsizers. It also limits the ability of workers to relocate to where skills are most needed, reducing the dynamism of labour markets and cities, she argued.

According to Powell, the economic cost is stark. “For every dollar it raises, around 70 cents of potential economic activity is lost,” she said. “By contrast, raising the same amount through a broad-based land tax costs the economy less than 10 cents.” She added that the volatility of stamp duty revenues also exposes state budgets to damaging swings, while the tax falls disproportionately on younger Australians and frequent movers.

Domain singles out the ACT as a model for reform, having begun a 20-year transition from stamp duty to a broad-based land tax in 2012. This approach, Powell pointed out, “avoided fiscal shocks, gave households time to adjust, and ensured all properties contributed to revenue.” However, efforts in other states, such as NSW’s short-lived opt-in model for first-home buyers, have faltered without bipartisan support.