Today’s photos come from reader Ephraim Heller, who took them in Brazil. Ephraim’s text and captions are indented, and you can enlarge his photos by clicking on them.

A Spurious Tale

It was a typical birding day, squatting beside a water hyacinth-choked waste lagoon at a cattle ranch in Brazil’s Pantanal watching giant rodents and caimans slither in the muck and waiting for something to happen involving birds.

A capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), the largest living rodent, surfaces amongst the water hyacinth in a sewage lagoon:

I noticed southern lapwings and wattled jacanas squabbling along the shore. These are common birds but of interest to me because I have never been able to capture decent flight photos: they have evolved the ability to always fly directly away from the photographer. I slowly squat-walked along the banks and they allowed me to approach as they bickered and fought. I started snapping close-up photos with my big 540mm lens when I suddenly stopped dead in my tracks: that lapwing has nipples.

A southern lapwing (Vanellus chilensis) displaying its “nipples:”

I got an A in my last biology class (AP high school bio in 1980) so I immediately grasped that the stale scientific consensus about the differences between birds and mammals was wrong. I guardedly approached Fito, our guide. Fito is one of the top 5 birding guides in all of Latin America and I had already established my credibility when I hired him and explained that my wife is a birder, but I just want to photograph the colorful and pretty ones. I showed him my photo and, in a tone as nonchalant as I could muster, asked “What are those?”

“Wing spurs,” said Fito.

“Wing spurs,” I sagely repeated. I had no idea what he was talking about.

I went back to my station beside the sewage lagoon and began shooting again. Further photographic analysis reveals two important observations that could potentially cast doubt on my nipple theory: “wing spurs” indeed emanate from the lapwings’ wings and they are retractable:

I turned my attention to the wattled jacanas (Jacana jacana) as a bully mercilessly chased away another jacana every time it landed. They ignored me as I shot. My shutter speed of 1/2500 sec froze the action. I paused to check that my images looked all right when I make yet another discovery – wattled jacanas also have wing spurs:

I shuffle back to Fito.

“Fito, are lapwings and jacanas closely related?”

“No.”

I walk over to my wife and show her my photos.

“Remember what I told you about hoatzins?” she asks. We had seen lots of hoatzins the previous week in Brazil’s Amazon. I remember that years ago my wife had told me about these strange birds that are born with claws on their wings. Before they can fly, they evade predators by dropping from their perches on branches overhanging the water, swim away from the danger, and then use their claws to climb back up a tree. As they mature their wing claws disappear.

Adult hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin) – no visible claws on their wings:

“Isn’t this an interesting example of convergent evolution?” I say.

“Maybe it’s not convergent evolution. Maybe it’s an atavistic trait. From the dinos.”

While I hate it when my wife one-ups me on speculative nature theories, I have to admit that now I’m intrigued. Do wing spurs represent a cool example of convergent evolution or an even cooler trait left over from the dinos?

I do a quick internet search on wing spurs. Another bird we have just seen in Brazil also has wing spurs. Behold the southern screamer, presumably with its wing spurs retracted:

Now I was getting suspicious. My generation remembers the warning from James Bond’s archenemy Auric Goldfinger in the Ian Fleming novel and 1964 movie Goldfinger: “Once is happenstance. Twice is coincidence. The third time it’s enemy action.” Lapwings, jacanas, hoatzin, and now screamers. What would Auric say?

Herewith everything I’ve subsequently learned about wing spurs.

Wing spurs are structurally distinct from talons or claws. Spurs usually project from the carpometacarpus, are covered by a keratin sheath, and are not used for perching or seizing prey. Unlike digit claws, which develop from the terminal phalanges, spurs are fixed, weapon-like appendages.

Wing spurs are present in several bird orders but are relatively uncommon overall. Wing spurs seem to have evolved independently in several modern bird families. These include some species of screamers, steamer ducks, spur-winged geese, lapwings, jacanas, stone-curlews / thick-knees, and swamphens present in the new world, old world, and Australia. These families are only distantly related: lapwings, jacanas, and screamer clades all diverged at least 50 million years ago.

Across taxa, wing spurs are primarily used as weapons—employed in intraspecific combat, territorial defense, or predator deterrence.

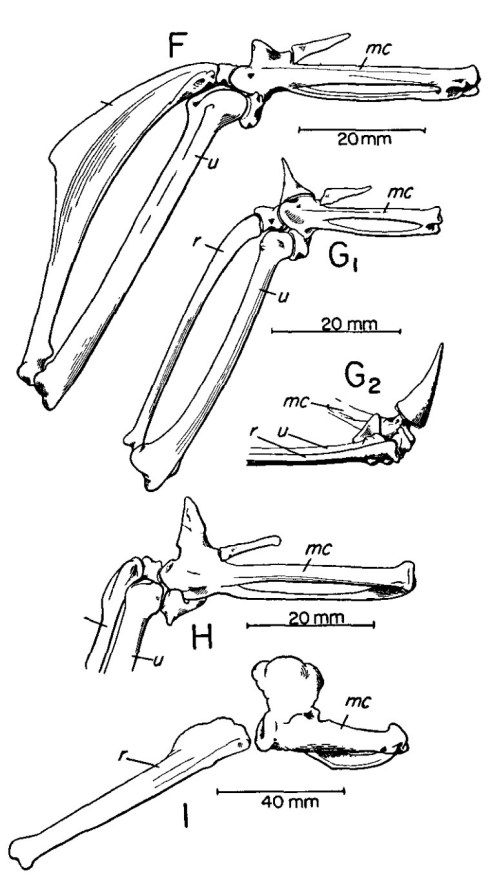

L. Rand published a detailed account of wing spurs in 1954 (available at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/wilson_bulletin/vol66/iss2/8). He observes that “spurs are projecting bony cores with an outer layer of horn, similar to the horns of cattle” and, surprisingly, that “the horny covering of the wing spur, in some species, undergoes molt.” He provides the following diagram of wing spurs in: (F) African jacana (Actophilornis africanus); (G1 and G2) northern jacana (Jacana spinosa); (H) southern lapwing (Vanellus chilensis); and (I) Rodrigues solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria).

In contrast to the wing spurs of modern birds, many basal avian dinosaurs, including Archaeopteryx and Anchiornis, had clawed fingers on their wings. These claws are homologous to the finger bones in modern birds, and in rare cases such as the hoatzin, vestigial claws are still present in juveniles. These are not carpal spurs, but true digit claws, aiding chicks in climbing until they fledge, when the claws are resorbed. The hoatzin lineage is highly divergent; molecular estimates suggest a split from other birds at least 64–70 million years ago, possibly earlier.

Most importantly, both my wife and I were correct: hoatzin claws may be an atavistic trait related to the dinosaurs, while the wing spurs of other birds represent convergent evolution. How cool is that!