Mental health treatment is expensive and hard to find, so it’s no surprise that people looking for empathy and care are turning to large language models like ChatGPT and Claude. Researchers are exploring and validating tailored artificial intelligence solutions to deliver evidence-based psychotherapies. Just recently, Slingshot AI, an a16z-backed company, launched “Ash,” marketing it as the first public AI-powered therapy service.

It makes sense that people find it easier to turn to the chatbot on their phones and web browsers than a human — if you woke up anxious in the middle of the night and needed to talk to someone, would you wake your partner, kids, or friends? Or would you turn to the 24/7 companion in your pocket?

However, there’s no system to help people identify the good mental health AI tools from the bad. When people use AI to gather information about their physical health, most of the time they still visit a doctor to get checked out, receive a diagnosis, and undergo treatment. That helps reduce the risk of harm.

But for mental health, AI can easily become both the information provider and the treatment. That’s a problem if the treatment is harmful. ChatGPT, Claude, and Character.AI were not developed to deliver mental health support, and they have likely contributed to people experiencing psychotic episodes and even suicidal ideation. These harms motivated Illinois’ recent law to limit the use of AI for psychotherapy.

Companies like Woebot Health have attempted to develop mental health chatbots that meet the requirements of government agencies like the Food and Drug Administration. But Woebot recently shut down its product because the regulation process slowed the company down to the point where it was no longer able to keep pace with the latest AI technologies, its founder said. Psychotherapeutic AI tools should be regulated, but we also know that people are already using nonregulated AI to treat their mental health needs. Simultaneously, companies like Slingshot AI and Woebot need a regulation process that allows them to develop safe and effective mental health AI technologies without becoming obsolete. How can people find the right mental health AI support that will help, not harm them? How can companies develop safe and effective mental health AI that’s not outpaced by consumer technologies?

Slingshot AI, the a16z-backed mental health startup, launches a therapy chatbot

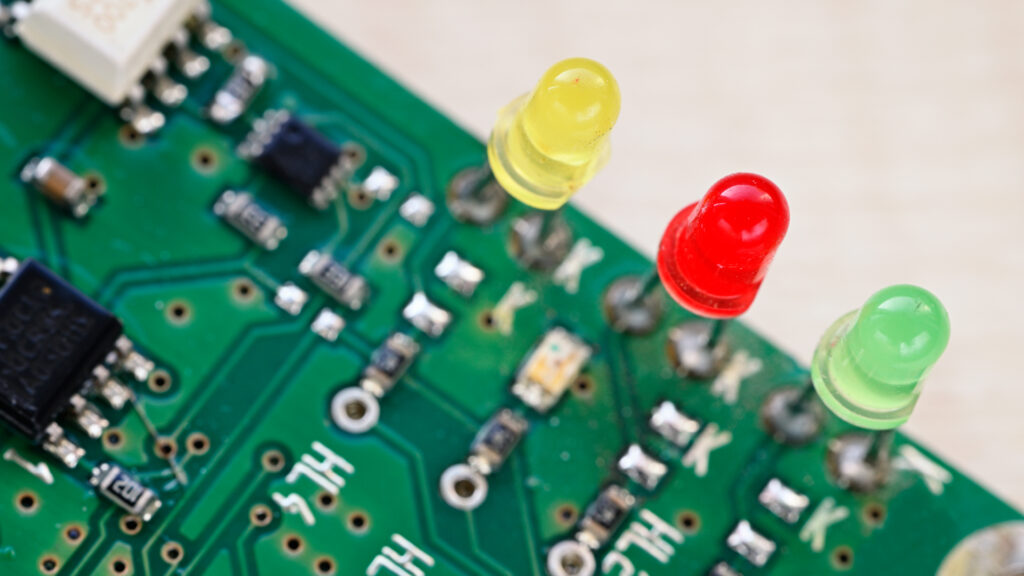

There is an immediate need for a new, agile process that helps everyday people find safe and trustworthy mental health AI support without stifling innovation. Imagine red, yellow, or green labels, or letter grades assigned to chatbots — similar to how we grade restaurants for food safety or buildings for energy efficiency. These labels could be applied to all AI chatbots, both those intended and not intended to give mental health support. An interdisciplinary AI “red teaming” coalition — including researchers, mental health practitioners, industry experts, policymakers, and those with lived experience — could grade chatbots against standardized, transparent criteria, and publish data to support labels given to specific products.

These labels would also provide feedback to industry on the mental health harms their products cause, with pathways for improvement. Labels would combine multiple criteria, including identified evidence demonstrating that the AI tools deliver effective mental health support in specific, real-world populations; data protection for users, including compliance with data privacy regulations; and risk mitigation, with validated algorithms and human oversight to identify and intervene on crises and inappropriate AI responses.

The labels we are proposing can build upon existing work. Organizations looking to certify or regulate clinical AI, like the FDA or the Coalition for Health AI, have developed guidelines to evaluate clinical AI technologies. However, the labeling process we propose needs to be more agile than FDA regulations — which slowed down Woebot to the point where the technology was outdated. To be agile, we propose a two-pronged coalition. First, a small, centralized organization could generate, publish, and annually reevaluate open source labeling criteria with community input. Second, external evaluators — composed of industry experts, researchers, individuals with lived experience, local community groups, and clinicians — could “audit” AI tools against the developed criteria each time the technology is updated, analogous to security auditing, scientific peer-review, or open-source code review.

AI’s dangerous mental-health blind spot

In addition, labels need a broader remit than the health care AI or software as a medical device products that organizations like the FDA or CHAI focus on. They must cover both clinical AI and the consumer AI that people repurpose for mental health support. The focus of these labels will also be more specific than other healthcare AI regulation: to assess whether chatbots follow evidence-based mental health treatment practices, and protect consumers from harm. While trade organizations like the American Psychological Association have developed guidelines to help mental health clinicians use AI, we call for labels that support mental health AI consumers, including patients engaged in clinical care and the general population. These labels can also combine ideas from emerging AI legislation in the E.U., California, and Illinois, but offer a more adaptable and globally responsive framework than specific regional efforts.

Governments have unfortunately shown that they are not nimble enough to be the arbiter of what is considered safe and effective mental health AI support. People have mental health needs and are turning to AI tools that are not fit for purpose. As we saw with Woebot, companies developing mental health chatbots through traditional regulatory channels are losing out to consumer AI that have avoided regulation. We want people to be able to get mental health support when they need it and incorporate the best AI tools, but we also want this support to be helpful, not harmful. It is time to think about new ways to help create a future for mental health AI that benefits everyone.

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org. For TTY users: Use your preferred relay service or dial 711 then 988.

Tanzeem Choudhury, Ph.D. is the Roger and Joelle Burnell professor in integrated health and technology and the director of the health tech program at Cornell Tech, and co-founder of two mental health AI startups. Dan Adler, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral associate at Cornell Tech and an incoming assistant professor in computer science and engineering at the University of Michigan.