I often hear a clear message in conversations or in political discussion: “Nuclear – that’s the solution: cheap, secure, and reliable.” For some market participants, the construction of new nuclear power plants seems to be the silver bullet for ensuring both security of supply and low electricity prices. But it really isn’t quite as simple as that.

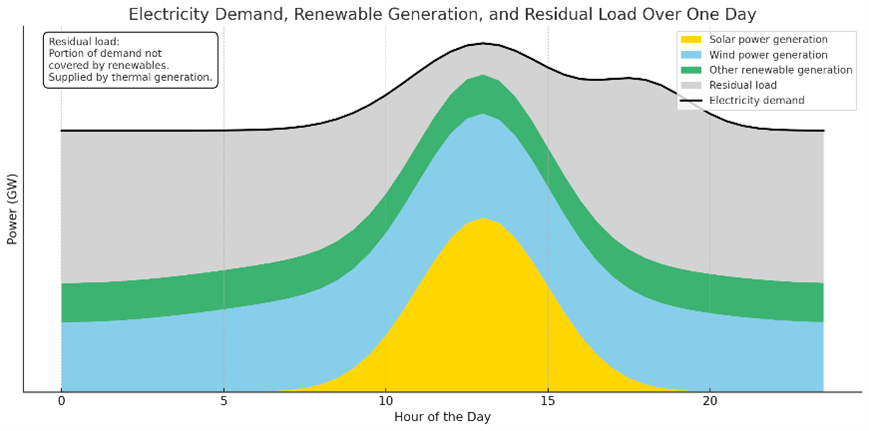

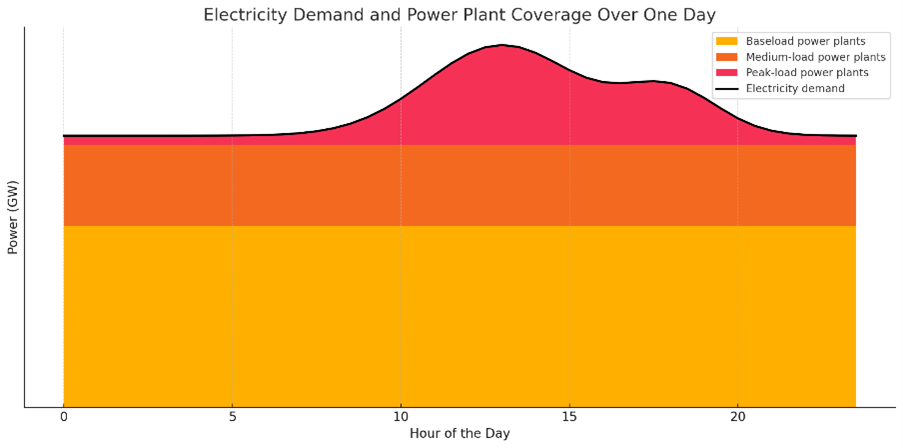

Let me explain. It’s not just a change from baseload, midload, and peakload plant operation. It’s a major shift to a system where renewable power sources lead the way, and thermal plants fill in the gaps.

What is less understood is this is not just a policy debate but a clash of system logic. This makes nuclear power and renewables fundamentally incompatible as sources of energy in a modern grid.

My colleague Clement Bouilloux discussed France’s green power paradox in his recent column. I noticed how clearly Germany and France are now diverging in their power system strategies.

From baseload to residual load

Traditionally, European supply followed a hierarchy. Baseload power, like nuclear and lignite, ran all the time.

Gas and oil are used during times of higher demand. This was a centralised, predictable architecture. But the dramatic rise in wind and solar has upended this approach.

Today’s reality shows a supply-driven market. The large amounts of energy from solar and wind turbines now meets more demand. The leftover load remains after renewables complete their part.

The following charts illustrate the difference between these two system approaches.

Image: Montel Analytics

Image: Montel Analytics

Image: Montel Analytics

Image: Montel Analytics

Germany: volatility as a principle

Germany has fully committed to this transformation. It closed its final nuclear power plant in 2023 and coal is to follow by 2038 (ideally 2030). Renewables already cover more than half of the country’s generation this year, with June hitting 73%.

The focus is now on combining renewable electricity generation with flexible solutions, which include battery energy storage, heat pumps, electric vehicles and electrolysis. This helps manage the changing residual load.

It also means accepting and even designing for, greater price swings. Economic signals shape the market by creating new types of flexibility. This leads to more ups and downs during the year, like high prices in winter and low prices in summer, while intraday fluctuations are increasingly volatile.

The German energy system now depends less on baseload power. It focuses more on controllability, which means flexible responses from both energy generation and demand. Large, inflexible, high-fixed-cost plants – especially nuclear reactors – no longer have a place. In volatile markets, the systemic and economic contradictions of nuclear energy emerge.

France: baseload in a renewable age

France has gone the other way, sticking to its nuclear-heavy identity. President Emmanuel Macron has declared a nuclear renaissance, sanctioning both new- builds and extended life for existing reactors. Many see the technology as a protection against price changes, imports and fossil fuel use.

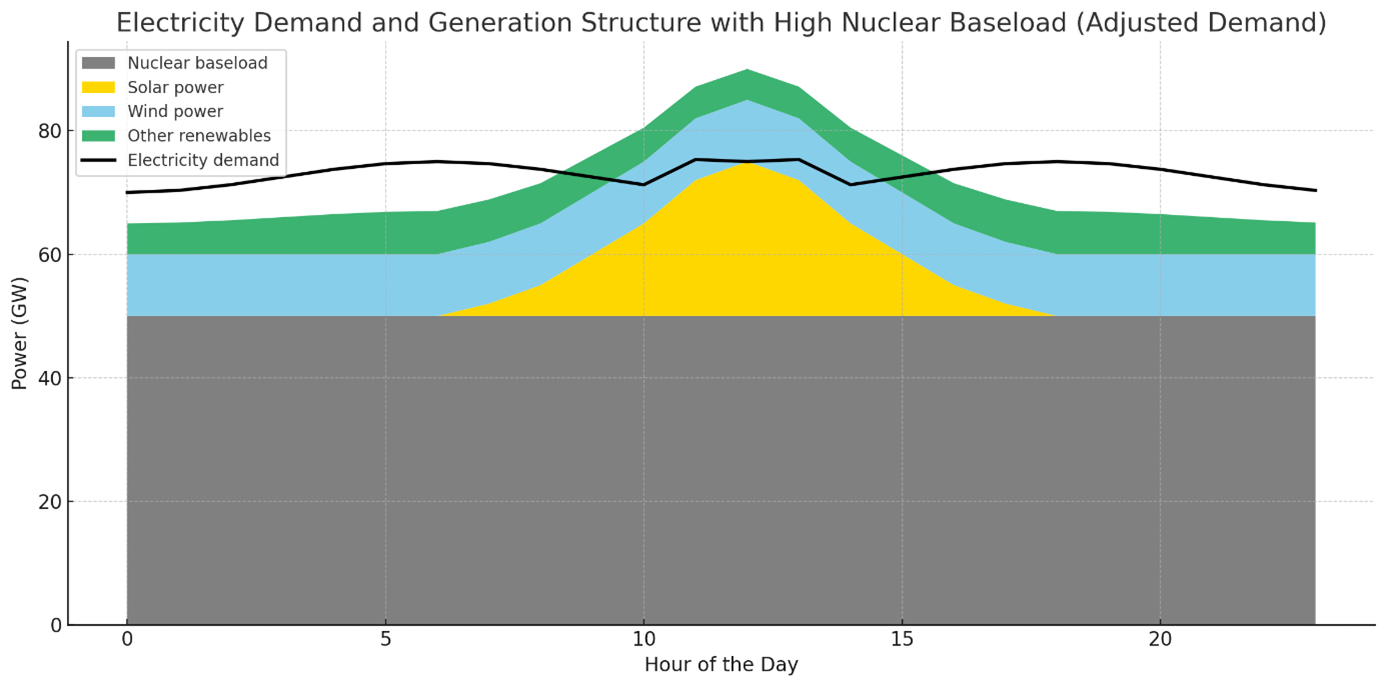

The EU is pushing for more renewable energy, however. In response, France is increasing its use of wind and solar power but this could cause more tension in the system.

These effects include:

Structural surpluses during sunny (and increasingly windy) periods, especially in summer.

Export pressure, often at negative prices, to neighbouring countries.

Flattened, sometimes low, power prices – eroding the value of both nuclear and renewables.

Underutilisation of nuclear assets, which rely on high full-load hours to amortise their fixed costs.

This chart is an example of the incompatibility of baseload power plants and renewable generation:

Image: Montel Analytics

Image: Montel Analytics

Systemic incompatibility

This isn’t just policy divergence, it’s a contradiction in system design. Baseload plants require continuous, high-load operation to be economical, particularly capital-heavy assets like nuclear. Technical flexibility is possible but costly and has hard limits.

Producers generate more renewable energy during the day from solar sources and at night from wind. This often forces baseload units to reduce their output or turn off and presents a challenge for nuclear plants, which are designed for steady production.

The old “load staircase” – baseload, midload, peakload – no longer fits a renewables-heavy, supply-driven market. Trying to maintain it risks a structural misalignment with reality.

No place for baseload thinking

Pursuing both new nuclear baseload and volatile renewables is not a coherent strategy – it is a conflict. The results: overcapacity, price collapses during renewables peaks, rising electric grid costs and inefficient investment on both sides.

Germany, with all its complexity, has chosen the path of flexible generation and demand-side readiness. However, France risks a future where neither its nuclear backbone nor its renewables push can deliver sustainable economics.

The lesson is therefore clear – in the new supply-driven paradigm, system logic matters more than tradition.

Please note columns will be published fortnightly during July and August.