My dad is there with me when I click the link, and commit to the class. He creeps up behind me when I unlatch the large U-shaped hook that opens and closes the gate to the court. He cheers me on as I hit a tennis ball for the first time in over 25 years.

He’s not there, not really. But in my mind he is. His head of thick dark hair, wearing his tennis whites, watching my every move.

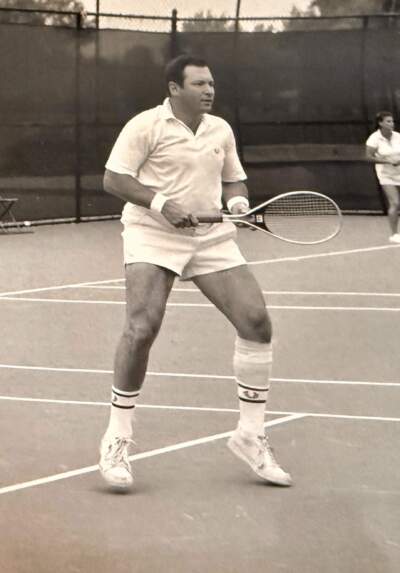

The author’s father, Lee Gunst, on the tennis court. (Courtesy Kathy Gunst)

The author’s father, Lee Gunst, on the tennis court. (Courtesy Kathy Gunst)

Stan, my instructor, introduces himself. Slightly sweaty and thick in the middle, he looks better suited to selling pot at a local dispensary than being a tennis pro. He takes one look at my racquet and asks how long it’s been since I played.

The racquet, which I think of as “modern,” is the last one my father gave me. It’s lighter than the wooden ones I grew up playing with, issuing a nice, satisfying ping when you hit it just right.

Stan explains that my racket won’t work and hands me a new, lighter-than-air racquet. Suddenly I realize it has been a long time. The game has changed and so have I.

My class has eight students, ranging from low-30s to me. At 68. I’m the oldest in the group. After 15 minutes of lining up to hit balls — first backhand, then forehand, a few lobs, playing at the net — the game starts coming back to me.

Some of the women in my class wear expensive-looking tennis dresses and fancy visors. The air of elitism is always what I hated about tennis; too clubby, too much of a cliché. But I am delighted to find that these women are so friendly — within 10 minutes of meeting, we share stories about child rearing, coping with the death of a parent. I feel at home.

My new “friends” cheer me on. I hit one so hard, so perfectly that I can hear my father — who has been gone for over two decades — screaming from the sidelines, “That’s it Katrina, hit it just like that.”

Stan says “Wow! Can you do that again?” I try, but the next one is a bust.

“How long did you say it’s been?” And then he says what everyone I’ve ever played tennis with in my adult life says: “You could have been really good.” As if it’s over and I missed my potential.

But I learned it’s not too late.

As a child, I spent weekends watching my mother and father play singles and then doubles. My father, one of the elite players at his club in suburban New York, could be found on the courts every day of the week. He would beg me to join him, offering to teach me to serve, to work on building more strength in my backhand.

Around the age of 10, I played with Dad in the late afternoons just before dinnertime, when he was finished with his real matches with his club friends. “Let’s have a private lesson” he would say with a wink. I remember loving the one-on-one time with him, just us two on the court, hitting the white Wilson ball back and forth. I took lessons at a summer day camp, but within a year or so, I lost any real interest in playing the game.

As a teen, I found it easy to find things to reject. Tennis, unfortunately, landed on my list of things I wanted no part of, along with the suburbs, playing card games and ladies’ lunches at the club.

Yet here I am, 50 years later, wondering why I couldn’t have found something less healthy to rebel against.

The author, as as a teenager, with her mother, Nancy, dressed in her tennis whites and her father, Lee. (Courtesy Kathy Gunst)

The author, as as a teenager, with her mother, Nancy, dressed in her tennis whites and her father, Lee. (Courtesy Kathy Gunst)

After we lost my father to cancer in 2001, I started obsessively watching tennis on television. Wimbledon, the French Open, the U.S. Open. I sat on my couch and rooted for Serena and Venus. I listened to John McEnroe commentate, hissing at his sexist comments. Watching my father’s beloved sport made me feel like he was there with me; it helped me grieve him just a little less.

And then last winter, after feeling sluggish, I thought “What if I got off the couch and stopped watching, signed up for a lesson and actually tried to play again?”

That’s how I found myself working on my backhand and serve at 68.

After that first lesson, and in spite of myself, I buy a short black tennis skort online. It arrives and I pair it with a sleeveless gray tank top, white socks and new blindingly white tennis sneakers. I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror as I leave the house, tennis racket and balls in hand. It’s my mother screaming “I’ll be at the club playing with the girls. Be home by 3!” And I think, isn’t this what I always wanted to avoid?

But I’m in Los Angeles, where I’m spending the winter to be close to my daughters and my granddaughter. And I’m headed to a public court taking group lessons that cost about $20. I tell myself to shut up, because this is me, this is now, this is doing tennis my own way. The truth is, I am getting so much joy out of it.

A new hobby as I near 70 is reason enough to feel pride. But returning to a childhood sport — something that defined your family, but something you rejected (and thought you were done with) — is worth celebrating. My lower back and wrists tell me it’s a bit late to begin again, but I don’t care. I leave every lesson beaming like a kid who had the best day at camp.

Here’s what I remember. It’s lesson #4. I’m in the groove. Slamming balls, like my old self. Stan says, “Time for doubles. When you win three shots you go to the other side of the court, the winning side.” My partner and I hit three winners. Easily. We shuffle off to the winning side. We win one, two, three, four more. I’m hitting like someone I don’t recognize. All the years seem to fly backwards and I’m there in some kind of timeless prime-time playing tennis. Not like the grandmother I am.

The shot comes close to the net and I remember thinking, you got this. I go into fourth gear and run. I can see the yellow orb, low but steady, and I need only two or three more steps, racket back and it’s mine and …

I’m on the ground. Face down. Get up, I tell myself, but I can’t move. I hear my fellow students gather around. I hear someone say “Oh s—!” I want to get up, laugh it off. Old lady down.

But something hurts; something hurts bad. I roll onto my back and lift my hand in the air. It’s throbbing. Three of my fingers are headed in the wrong direction. My middle finger points off to the left, like a directional heading down a dead end. My ring finger looks like it’s pointing in the opposite direction, my pinky is buckled in the middle, and my knee is screaming. My ribs ache.

An x-ray of the author’s right hand, showing two broken finger and a dislocated finger, after she fell on the tennis court. (Courtesy Kathy Gunst)

An x-ray of the author’s right hand, showing two broken finger and a dislocated finger, after she fell on the tennis court. (Courtesy Kathy Gunst)

A fellow student, a woman I’ve known for less than an hour, says “I’ll take you to urgent care.” But Stan has already called an ambulance. I need to call my husband. Somehow my phone appears and someone puts my face up to the screen.

Before I know it, an ambulance arrives. Two men are asking me questions. Do I take any blood thinners? Medications? How’s my level of pain? I’m on the ground, lost in a swirl of pain (and yes, embarrassment). And then, out of nowhere, my husband, John, appears. “Oh sweetie, I’m here,” he says. He almost never calls me sweetie. I hear one of the young women say “He’s amazing! I think I’m in love with him.”

And then I’m inside the ambulance and they’re giving me something. Morphine? There is a dark grey wool blanket coming up over my head and covering my body and the pain is somewhere, still there, and yet not.

At the ER, they tell me I need surgery, right away. Two fingers broken in several spots. The third finger is dislocated. I also have a broken rib. The ER doctor puts my fingers in a temporary cast (surgery will be days later). I wake to pain and a big fat cast that makes me look like I’m trying out for the role of Captain Hook.

It’s been six months since I had the surgery. My pinky is still bent in the middle, but thanks to months of PT, I have regained strength and dexterity in my right hand.

The author, in the black hat, and her tennis instructor Nick and friend, Allison. (Courtesy Kathy Gunst)

The author, in the black hat, and her tennis instructor Nick and friend, Allison. (Courtesy Kathy Gunst)

Earlier this summer a friend called and asked if I wanted to play tennis. I was told it was “safe” to play after five months, but I hesitate. What if I fall again? What if I lost all my new-found ability? What if? What if?

We meet at the public courts near my friend’s home. I quickly explain that I’m not willing to run for any crazy balls. I tell her I need to get back into it slowly. But within 10 minutes, I feel the exhilaration, the thrill. My right hand seems to be relatively happy to be back at it. No protest, cramping, or crippling fingers. I relax into the game.

When I hit the ball just right, and it makes that “thwack” sound in the middle of my racket, I feel a tingling through my body — call it endorphins — like nothing in the world matters except smashing this ball over the net. It’s like a perfect dance move or hitting the note in a song just right. I remind myself that I am learning something new, something I don’t find naturally easy at an advanced age, and that makes me love the game even more.

My friend calls out, “Hey, do you know you’ve got a big smile on your face right now?” I am not aware, but I’m also not surprised.

My dad is there, again watching over me, and he smiles. “You got this, Katrina.”

Follow Cog on Facebook and Instagram. And sign up for our newsletter, sent on Sundays. We share stories that remind you we’re all part of something bigger.