In the early 1990s, Australia, along with other wealthier countries, promised to give “new and additional” funding to help developing countries address issues associated with climate change. This is what we now call “climate finance”.

Money is no substitute for wealthier countries reducing their emissions, but it does have the potential to help developing countries. However, whether climate finance will assist or not depends on many things: including whether donors actually stick to their promises and give new and additional money. In Australia’s case, at first glance, it seems like it might be. Australian climate finance is, according to official figures, rising.

In our new Development Policy Centre discussion paper, we study one component of Australian climate finance – bilateral aid given to help countries adapt to the effects of climate change – and interrogate the data. We focused on bilateral adaptation aid because it is the single largest component of Australian climate finance at present. Also, unlike some forms of funding such as private climate finance, aid is comparatively transparent. OECD data is available on a project-by-project basis and details whether donors consider particular projects to be: “not climate related”; “climate principal” (fully focused on climate issues); or “climate significant”, which means projects where climate considerations have shaped the design and operation of the project in important ways. Helpfully, OECD data are also what donors tallying up when they make their claims about how much bilateral climate aid they are giving.

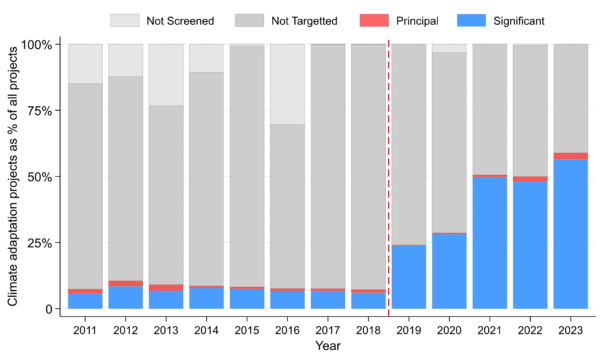

When we dug into the OECD data for Australia we found that, commensurate with overall trends in Australian climate finance, reported climate adaptation aid has been going up. So far so good, although — unsurprisingly given that overall Australian aid isn’t going up — we also found that that the nominal increase was the result of an increasing share of Australian aid projects that were claimed to be adaptation related. In particular, as the chart below shows, the nominal rise was a product of a rapidly increasing share of projects being claimed to be adaptation significant. A rise that kicked off abruptly in 2019.

Figure 1: The percentage of Australian aid projects claimed to have a climate adaptation focus

Source: Assessing Australia’s allocation of climate adaptation aid discussion paper.

And this is where the problem lies. Climate aid reporting to the OECD isn’t audited or policed. As a result, donors have a lot of leeway to interpret whether projects are climate related or not. In the case of “climate principal” projects, unless you’re going to be utterly brazen about it, the leeway is less: either a project is all about addressing climate-related issues or it is not. However, there’s just enough wiggle room in the “significant” category to allow donors to claim, should they so wish, that a project is climate relevant even when linkages are very tenuous. This is more than a theoretical problem: international studies have found creative climate accounting practices amongst other aid donors.

In Australia’s case, we found evidence of the same problem. We also found evidence that the problem has contributed to the rapid nominal rise in Australian climate aid.

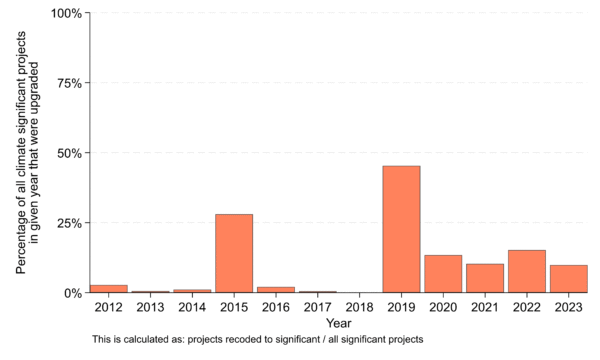

As the chart below shows, we also found a worrying number of projects that had once been said to be unrelated to climate change suddenly became, for some reason or another, viewed to be climate significant in 2019.

Figure 2: Percentage of climate significant projects in any given year that were upgraded

Source: Assessing Australia’s allocation of climate adaptation aid discussion paper.

There are potentially reasonable grounds for reclassifying projects. In particular, “mainstreaming”, which means designing, or in this case redesigning, projects so that they take climate concerns into account in a meaningful way. This is not the same as giving new and additional climate aid, but it can be good aid practice. And, as we note in the paper, DFAT appears to be taking the task of mainstreaming seriously. However, real mainstreaming takes time. And it is very hard to see how so many projects could have been redesigned between 2018 and 2019 to incorporate climate change sufficiently to warrant being classified as adaptation significant. What’s more, when we sampled projects, we found examples — such as a transport project in Papua New Guinea, and a private sector investment project in Fiji — where the recoding seemed questionable, particularly as nothing obvious about the projects appeared to have changed.

To make matters worse, when we ran regressions to see where projects were most likely to be adaptation related, we unearthed something unexpected and concerning.

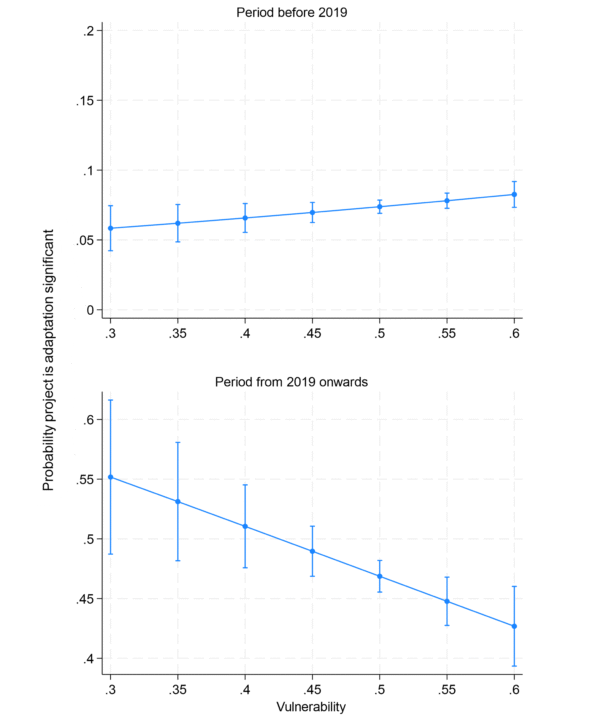

Throughout the period covered by our data, aid projects were always more likely to be climate adaptation principal when undertaken in countries that were more vulnerable to climate change. Prior to 2019 the same was true for adaptation significant projects. This is great: focus on climate adaption when giving aid to countries where it is needed most.

However, in the period from 2019 on, the pattern reversed for adaptation significant spending: projects in countries particularly vulnerable to climate change became less likely to be adaptation significant than projects in places that weren’t as vulnerable. You can see this in the chart below, which plots the probability that a project will be adaptation significant on the y-axis and the climate vulnerability of the country they are in on the x-axis. (These are margins plots based on multinomial logistic regressions with a wide range of control variables included.)

Figure 3: Country vulnerability and the probability a project will be adaptation significant

Source: Assessing Australia’s allocation of climate adaptation aid discussion paper.

This is a problem: in its haste to increase its nominal climate spend Australia is — on paper at least — focusing more attention on climate adaptation in places where it is needed less. Some of this change, particularly that stemming from recoding in 2019, probably had little effect in practice. However, subsequent trends likely did reflect real changes. DFAT, as we have pointed out, appears to be taking mainstreaming seriously. This is good, but potentially problematic in two ways: first, projects that have other laudable central objectives such as improving health should not be reconfigured simply to meet climate finance promises. Second, the effort required to change projects where adaptation does genuinely need to be incorporated, ought to be focused foremost in places where the impacts of climate change will be worst. Our findings suggest the opposite has occurred.

There’s a much better alternative to all of this: Australia could simply keep the promises it has made, increase its aid budget, and give genuinely new and additional aid to help developing countries adapt in the midst of the current climate emergency.