For all this hyperlocal culinary devotion, however, Indian cookbooks appear to have awoken very late to the need to document all the regional insights we’ve known all along, and are now busy playing catchup. In the past quarter century, over 50 regional cuisine books on virtually all parts of India have been published, buoyed by a swelling social media interest which shows no signs of subsiding. Why did this need emerge so late? What sort of new national culinary culture is this new tranche of cookbooks trying to produce?

I was in my late teens and my parents had just immigrated to Toronto when I began to ask my mother for recipes. Amma would return from work much later than I, and I needed methods to stave off the desperate hunger of after-school, pre-dinner hours. This was in the mid-1990s. Email was still just a college campus communication tool; nobody really could have predicted the large role the internet would come to play in culinary knowledge-transmission. Amma wrote out in elaborate detail preparation methods for arachuvitta sambar (sambar with freshly ground spices), poricha kuzhambu (a lentil-coconut mixed vegetable preparation) and the like—but these were dishes that made no sense for my urgent after-school needs. I learned instead to make chhola masala from the instructions on spice packets I would find in the shops on Gerard Street, and hung about the kitchens of friends’ mothers, picking up other ideas—including a corn butta in coconut milk recipe from one Ismaili aunty in our tenement.

Over the years, especially on my return to India in the 2000s, my queries to my mother became less basic. I wanted to know now about pickling mahali kizhangu, or the uses of native greens and other local vegetables whose rare virtues Amma would periodically extol. But now her standard answer was: “YouTube-la paaru. Check on YouTube; it has everything.” (In the distance, my father would grumble: “She will look on YouTube even for an uppma recipe…”)

Neither mine nor my mother’s stories are that unusual. I count Amma among those for whom all the early tranches of Indian cookery books had been written: young women without maternal tutelage, who’d left mothers behind, who’d been thrust into new lives in new places, and asked somehow to creatively perform without necessary training. Pulled out of one set of practices and moorings, pushed into unfamiliar worlds. “Samaitthu Paar!” Meenakshi Ammal had exhorted once, in her iconic post-independence cookbook of the same title: “Cook and See”. Cook and see what? I often wondered, watching my mother navigate new culinary environments in all the places she lived, uneasy about my own fraying moorings. But I dared never speak my doubts out loud.

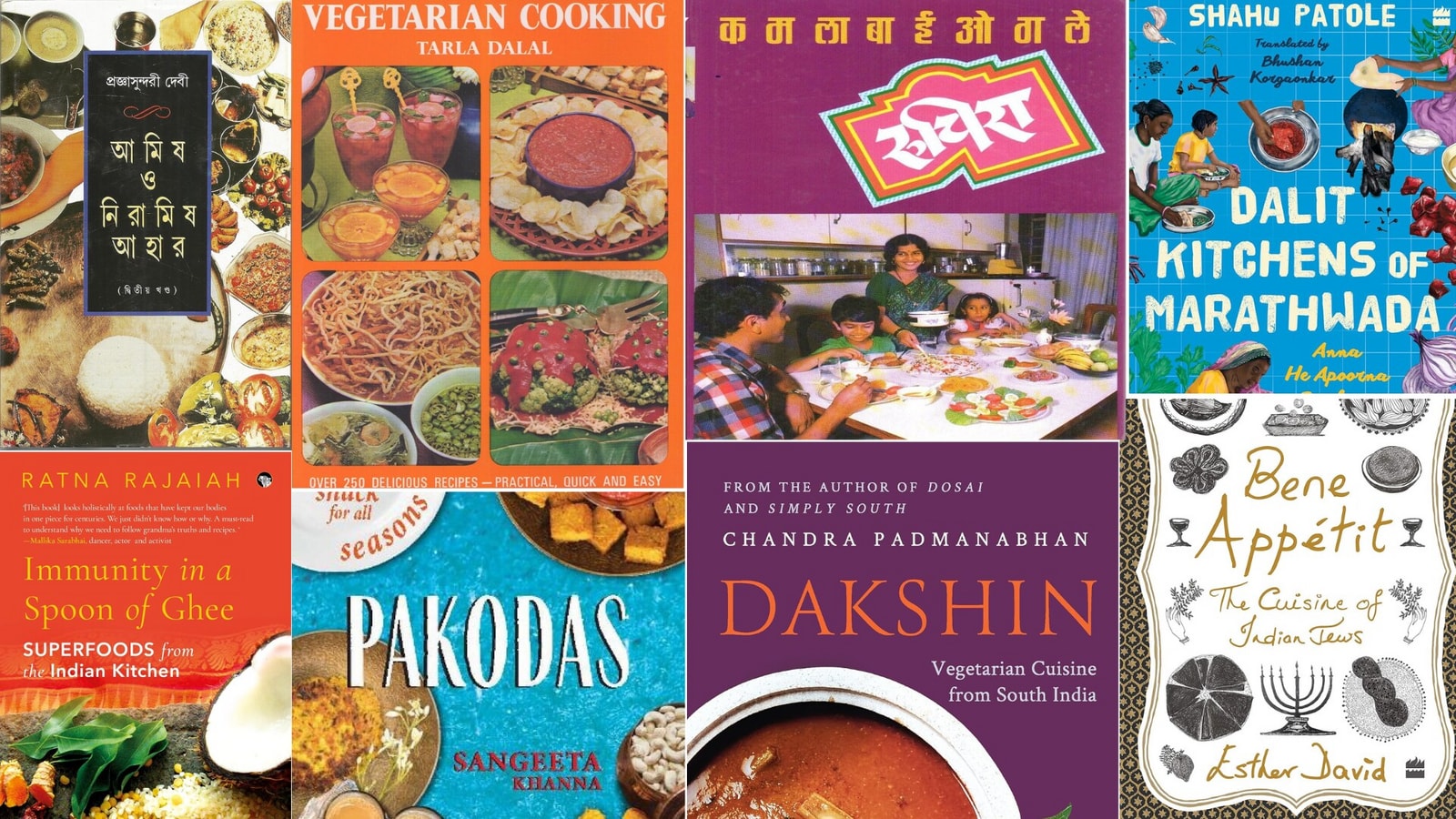

Cookbooks in India and perhaps elsewhere, too, have always been something of an answer to the culinary anxieties produced by sweeping, destabilising social changes. Prajñasundari Devi of the Tagore family wrote in 1900 in her book, Amish o Niramish Ahar/ Non-Vegetarian and Vegetarian Food, for instance, of wanting to save Bengali food from the disorderly “muddle of fish and milk-based dessert in our feasts … and confer on it order and discipline” of the sort once provided by scriptural tradition. But her two-volume set is by no means a pure traditionalist return. Alongside classic Bengali fare, multiple raw papaya and pointed gourd curries, neem-baigun (neem leaf-eggplant) fry and a taaler (toddy palm) kheer sits a Parisian chechki (dry, tempered stir-fry), tinned salmon cutlets, and preparations of cauliflower and cabbage, which were new vegetables at the time. Both her work and that of Bipradas Mukhopadhyay at the turn of the 19th century, says the scholar Utsa Ray in her book Culinary Culture in Colonial India, were “classic examples of the changing diet of the Bengalis” through decades of self-redefinition within the colonial encounter.

View Full Image

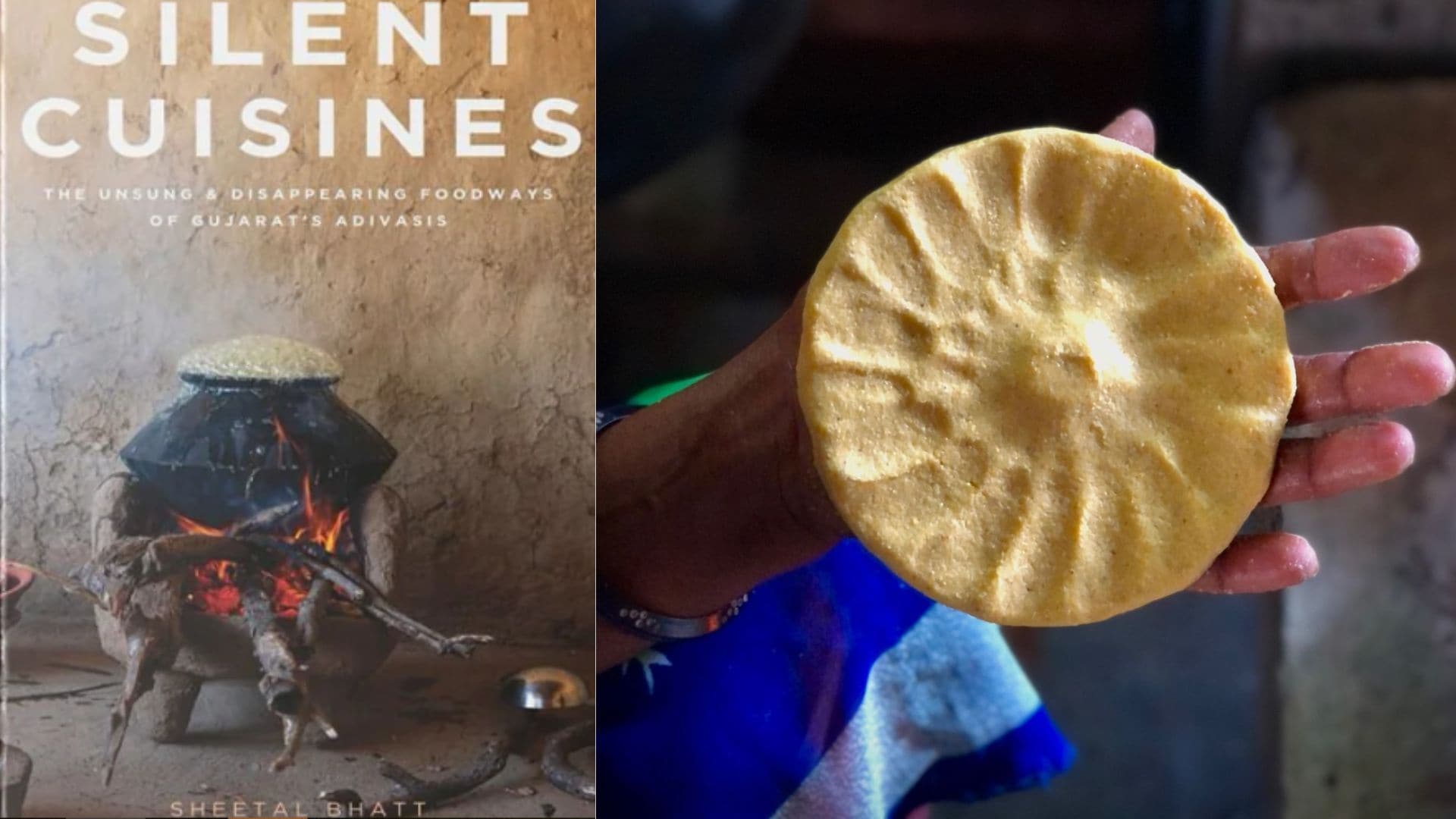

The book cover of ‘Silent Cuisines’ by Sheetal Bhatt; (right) each hand-sculpted ‘rotla’ wears the print of its maker (Sheetal Bhatt)

Just a half century later, the “midnight’s children” who were my mother, my aunts, all my aunties, some working professionals, many housewives, all coming of age in a rapidly modernising post-independence India were developing needs that would carry the changes further. This was not an elite class of urbanites but a professional and commercial bourgeoisie, unmoored from the agriculturally rooted lives of earlier generations, growing into new consumption styles. Arjun Appadurai wrote of them once, in his well-known 1988 essay on How to Make a National Cuisine, as becoming skilled cosmopolitans—moving seamlessly between “Swiss roll” jam-filled cakes and classic home food, everyday meals and show-stopping dinner-and-birthday-party spreads.

Such works in Indian languages were the less-feted precursors to Tarla Dalal’s blockbuster The Pleasures of Vegetarian Cooking (1974), which spoke to all of India in English in ways that even translations of Ogale’s work could not. Dalal demonstrated the grand versatility of being vegetarian. She also opened up possibilities of creative localisation by calling for ketchup rather than tomato paste in lasagna, or the use of ghee (or vanaspati, as was common then) in place of butter. Other compilations soon found other niches: Aroona Reejhsinghani—named “Culinary Goddess” by Femina—offered Tasty Dishes from Waste Items (1973), and Vimla Patil wrote for an emerging workforce The Working Woman’s Cook Book (1979). Such works reiterated the need for simplicity, speed, and economy in the face of changing home, kitchen, and career demands.

Each of these authors addressed themselves to peers and young women navigating new worlds, via cooking lessons and their written receipts, their efforts taking the place of maternal tutelage. A later edition of Ogale’s Ruchira would proclaim her “One mother to two lakh daughters-in-law”, owing to the book’s unexpectedly high sales. Still other works like Malti Dalal’s encyclopaedic 1975 Gujarati Chalo Rasodama invited, in its title, tone, and narrative flow, daughters to enter the kitchen and learn the ways food aided in the navigation of what Tagore had for Bengal called ‘Ghare Bhaire’: the home, the world. But now the world is your oyster, these cookbooks seemed to say in new maternal voices, so here’s how to navigate it.

The early writers codified food to make us the moderns we sought to become, but they also missed a chunk of who we already were. Looking back, the image of an eggless soufflé arriving at a grand dinner table with suitable pomp seems out of touch with the ways in which a great many Indians actually ate, even in those times. This is not to say this older generation of cookery books had no traditional recipes. Intent on simplifying and codifying, however, they subsumed the immense depth and diversity of Indian insights into generalised, stereotyped “Punjabi-Madrasi-English” subheads. They taught ways to cook, and communicated essential food wisdom; they preached on health, hygiene and even nutrition science. The 1962 Tea Time Eats by the Madras Diocesan Press, for instance, is openly didactic, introducing Anglicised terminologies for the preparation of what are evidently common Tamil snack items, and selling nutrition flash cards and even flannelgraphs as teaching aids alongside—as though concepts of nutrition were alien and needed teaching.

View Full Image

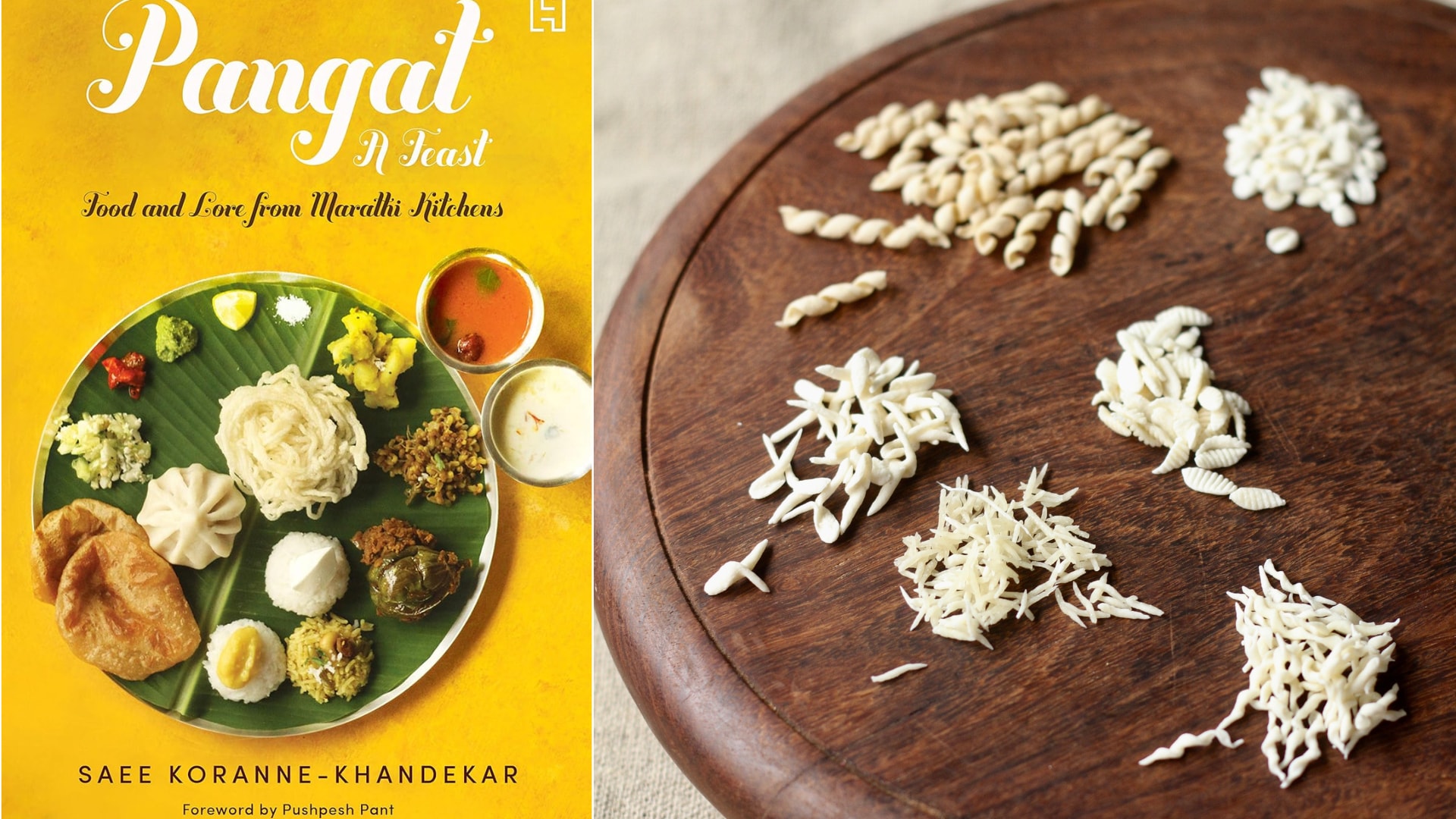

The book cover of ‘Pangat A Feast’ by Saee Koranne-Khandekar; (right) ‘vaalvat’ is a tradition of handmade, sun-dried edible crafts.

A clear sense of place and origin was also missing. The urbanised food of a particular class or community often stood in for the food of entire states or regions, discernible only to those who already knew. Regional, community-based, traditional methods, with all their many unique gustatory and medicinal insights about food, its ecologies, its procurement, its preparation, and its consumption—all these things were not just absent, they were in effect sidelined.

Housewives continued to publish vernacular chapbooks of home recipes and sold them through local kitty parties and bhajan gatherings, but limited circulation kept such works from gaining influence. Meanwhile, Tarla Dalal’s next Indian Vegetarian Cookbook (1984) cursorily recognised the regional differences between Bengal and Punjab, but mostly to say that the former has a diet so fish-based, its vegetarian specialities are few. We understood each other largely via a series of greater and lesser stereotypes: Bengalis eat fish plentifully, Gujaratis put sugar in everything, Malayalis fry everything in coconut oil, Andhra food is numbingly spicy. Any finer differentiations or local and seasonally attuned forms of eating remained woefully undocumented.

FROM INDIAN VILLAGE TO INTERNET

I’d like to say that the internet changed everything, but first what it did was make it possible for our mothers to platform their guidance for daughters in diaspora. “Ammas.com” did just that, reiterating a virtual maternal bloodline, still with a mix of recipes but with increasing regional distinction: panasakaya koora (green jackfruit curry) from Andhra Pradesh alongside the now-markedly Mughalai zaffrani gosht (lamb chops in saffron gravy), for just one example.

Far away from home, displaced from the village lives of our grandmothers, far apart from mothers, aunts, and other mother-figures, what we in this next generation of moderns needed was not more cosmopolitan schooling, but ancestral roots which were everywhere undermined and fraying. For me, these came via books like Chandra Padmanabhan’s Dakshin (1992), whose largely Tamil brahmin recipes allowed me to pull together bits I already knew into full-fledged meals. Amma’s Cookbook (2001) after the Amma’s website gave me some connective threads with the Andhra family into which I had married, but it was really after Y2K that early blogs like Indira Singari’s nandyala.org started to fill critical gaps. Hers were largely recipes from her hometown of Nandyala, and no longer the programmatic listings that earlier books had been. Blogging space and dramatically improved visuals, compared to the dull photography of earlier cookbooks, transformed recipes into intimate accounts of lives and longings. Blogs quickly became dreamscapes, methods by which to find “home” across insurmountable divides, via that specific taste of a rustic peanut chutney or a mirchi ka salan—even if it did now accommodate red bell peppers or jalapeños.

Focused regional or community recipe collections had not really existed before internet blogs and the books that emerged from them turned recipe writing upside down. Ummi Abdullah’s Mopplah chronicling in Malabar Muslim Cookery (1981) and perhaps a few others are notable exceptions. The internet age only enhanced this awareness of regional and cultural distinction—perhaps because there were now so many more who could convey the minutiae of their own culinary experiences. There was also a discernible shift in purpose. Recipes were no longer just cooking instructionals, but expressions of an aching urge to find, revalidate, and restore all that an earlier generation had left out of the story of food: lineage, traditions, local ingredients, family practices. Sheetal Bhatt said it all in her blog’s name: it was the “Route to Roots.”

Was it a generational sense of loss, the need to record all our mothers’ recipes before it’s too late? A way of growing ourselves out of those long generational shadows? Or a response once again to the yawning chasms of modern life that separate us more and more from greenery, villages, foraging areas, the traditional kitchens and agrarian customs that defined our grandmothers’ lives? Was it just that we missed home? Did we start to see our own foodways as one among many? Or were we just tired of having the food whose rich variety we knew so intimately reduced to idli-sambar, dhokla-thepla, dalma or other such standard regional signifiers?

Whatever the prompts, the space of culinary documentation has exploded both digitally and on printed paper, lending credence to my mother’s claim that these days you really can find everything on YouTube. But not just on YouTube. We now have dedicated cookbooks from well near all Indian regions, though the central and north-eastern states are less represented than others, and Rajasthan’s many cookery books tend to overly favour royal fare.

Many are family or community-specific cookbooks, standing in still somewhat imperfectly for a region’s cuisine. De Leij: Culinary Art of Kashmir (2011), for instance, is a record of Kashmiri Pandit cooking set within a broader celebration of Kashmir. It includes some Muslim dishes, and, in its online presentation, is set alongside distress over the community’s exile from the Valley. The Pondicherry Kitchen (2012), by contrast, makes no mention of the city’s many other culinary traditions—though Lourdes Tirouvanziam-Louis, the book’s author, did tell me in conversation that she had documented her (Tamil Catholic) community’s food, and that her own Chettiar friends did things differently.

Other works are similarly more-and-less self-conscious documentations of whole geographic areas (Annapurni, 2015; Paat Pani, 2018; Pangat, 2019; Pachakam 2022), sometimes broken down into sub-regions or community micro-cuisines. Still other works focus entirely on community micro-cuisines: Esther David’s Bene Appétit (2021) tells the story of the Bene Israel Jews alongside their recipes, while the self-published Yummy Sourashtra (2018) simply assembles the recipes of the Madurai Sourashtra community. This community proudly traces its lineage back to a guild named in the 437 CE “Mandsaur (Mandasor) Inscription of the Silk Weavers”—though the stories and legends of their migration and final resettlement under the Nayakas in Madurai are (sadly) not covered in the cookbook itself.

View Full Image

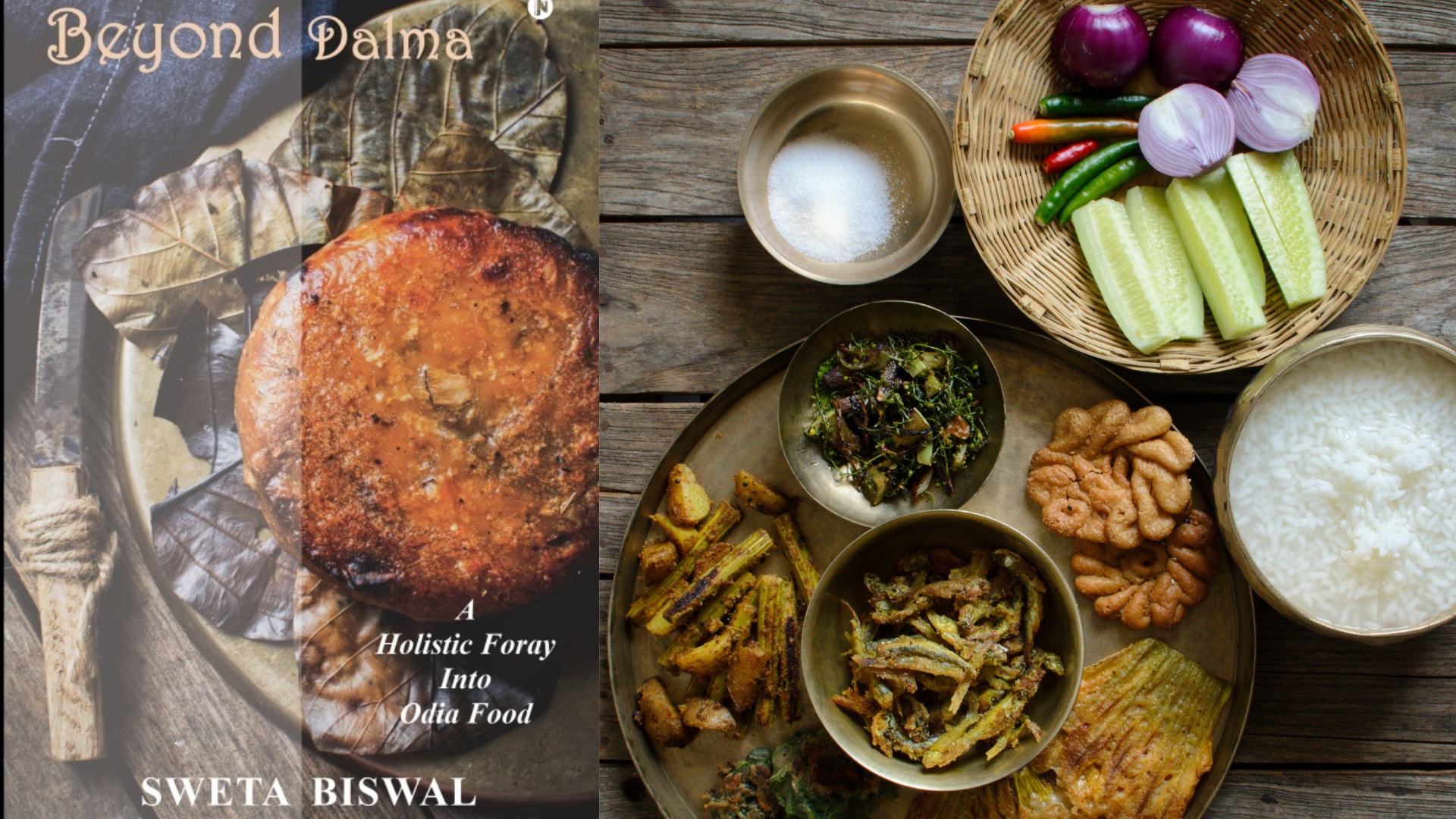

Book cover of ‘Beyond Dalma’ by Sweta Biswal; (right) a meal cooked during the month of May.

No doubt, these new cookbooks tell you the “who-and-where” of food in greater depth than ever before, but there’s a great deal more at stake, too. What all, really, did the process of becoming moderns cause us to forget? Sweta Biswal’s Beyond Dalma (2023) offers an answer; it is the only book I know that is organised as a seasonal recipe guide to Odia food. The meal, as constituted superficially by starters, a main course, condiments, desserts plus the supporting cast of masalas and spices, takes second place in Biswal’s work. Instead, the book is chaptered by the months of traditional Indian calendar, each associated with a season, and not just the availability of certain ingredients but equally the suitability of certain preparations for the body in this time. We begin with Baisakha (April-May), around when most Indian regions celebrate the new year. Agro-ecology is the underlying organising principle, vital to the Odia understanding of food. Within this reconstituted framework, unusual ingredients like arrowroot and skunkvine become important, and the simplest of rice gruels made with peanut milk from Bonaigarh can take centre-stage. Simplicity, speed, and efficiency are once again key—but as celebrations of traditional ways, not as concessions to modern lifestyles.

The kind of tacit pushback we see in Biswal’s Beyond Dalma to the conception of Indian food as too-involved, time-consuming, or nutritionally suspect because of a heavy reliance on rice (carbs) or ghee (fats) appears elsewhere, more loudly expressed. Sangeeta Khanna’s Pakoda (2019) recovers the nutritionally reviled but culturally beloved fritter by simply demonstrating its extraordinarily wide range as a snack food. A botanist and nutritionist herself, Khanna presents the pakoda as a place where the ingenuity, thrift, and zero-waste values of Indian cookery express themselves.

There are superfoods in every Indian kitchen, adds Ratna Rajaiah in her Immunity in a Spoon of Ghee (2023), encouraging us to eat as our grandmothers did and to find good health not in the chemist’s cupboard but in the most basic of Indian preparations like curd rice or sambar sadam. Hers is a reminder of the old, cherished Tamil Siddha precept: unave marundu, marunde unavu, food is medicine, medicine is food. Look at your own food anew via the lenses of the past, these works encourage; all you need is already there contained. Then even the famous Sourashtra street food, pankarapaan beiri, podi-dusted vadas made with a trio of medicinal greens (kalyana murungai, murungai, thoothuvalai) start to make sense as a “health food”. The point is not that they are deep-fried. The point is that we would never eat these rarer greens regularly unless they were made palatable in these ways.

Dipali Khandelwal of “The Kindness Meal,” a project dedicated to the preservation of sidelined and disappearing food cultures, told me once that the foods given to guests in humble Rajasthani homes are not the ones they consume. Paneer rules; native melons, foraged greens, or fermented porridges do not. Those “silences” of the ignored, the sidelined, the under-valued, under-represented foods and foodways that have no representation in mainstream cuisines, but which are treasure troves of traditional wisdom and attuned cultural understanding become the central focus of Sheetal Bhatt’s recently released Silent Cuisines (2025). Here the recipe for a sunn hemp fry is set alongside the much longer story of this ingredient, told in the voices of the Adivasi communities who have been the custodians of this knowledge and these methods.

If “eating is a political act,” as Wendell Berry said long ago, it is also a fundamentally restorative one, by which each bowl of maize flour raabdi (porridge) or khichri returns us to the ignored and rapidly disappearing agrarian landscapes in remote, “silent” corners of Gujarat. We learn of companion plants, customs that handed down from times when cultivated food was scarce. If there is a dinner party to be had here, it happens next to fields, in kitchens shaped by hand in mud, and under the stars. Bhatt’s work is the very picture of what the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins called “original affluence”—ecological abundance that was both enough and plenty, because it was held up by a vast knowledge of what to eat, and when, and how.

Bhatt takes pains to show the hands that made the dishes she records and photographs, in situ, and is fond of noting how each rotla made carries the signature finger-marks of its maker. Likewise, Sapna Ajwani’s account of a cuisine that emerged from a community’s flight from Sindh during Partition (Sindh, 2024) makes room for recipe credits alongside historical detail and suggestions for wild greens and other native ingredient uses. Such gestures are particularly meaningful in a space that has no real conventions for crediting or acknowledging recipe creators, and where idea-and-image theft is common. Showing images of hands, introducing “hosts,” naming names are some of the ways in which cookbook writers offer models for collective acknowledgement and shared authorship.

“Get a real plate,” an American friend once suggested when we ran out of glassware and I got myself a rimmed stainless-steel dish. I recall wincing—and then, years later, feeling relieved to see as many terracotta chattis, aluminium kadhais, and “eversilver” dishes as chic ceramic bowls gracing the visuals of Archana Pidathala’s Five Morsels of Love (2016), and leaves-as-plates in Sheetal Bhatt’s images.

Shahu Patole tackles other forms of embarrassment head-on in the Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada (2024), originally published in Marathi. A riposte to “sattvic” class-caste cleansed vegetarianisms that are entirely incognizant of Dalit realities, the book claims a rightful place amidst our much-vaunted diverse culinary traditions. We may not ourselves cook offal, but recipes insist that we engage the lifeways that have been compelled to. We may venerate and valourise pastoral traditions that give us milk, butter, ghee and curd, but here we face the brute realities of pastoral economies which are equally centred around beef. The democratisation of food made possible by social platforms has not always fostered equal representation, and has romanticised and glamorised everything. This book alerts us to the inherently dual nature of all our food systems by bringing Dalit history and realities on to our plates, too.

No doubt, the books published in the last quarter century vary considerably in look-feel, scope and quality—but this is not to undermine their value. Not living with our parents in large joint families any more, being further and further removed from all the older ecological and cultural sources of ourselves, these cookbooks no longer pretend that being modern is preferable or at odds with being rooted and local. Instead, they each are layered exhortations to the memory of being in place, even to what Appadurai in another context has called “ersatz nostalgia”: nostalgia for experiences we have not ourselves had. Or, as Deepa Chauhan of 2023 MasterChef India fame said to me once, they are “your first point of contact when you’re lost for knowing what to do” and needing to cook your way out. I remembered Meenakshi Ammal then, and understood suddenly what she had wanted us all to see.

Deepa S. Reddy is a cultural anthropologist and researcher with the University of Houston-Clear Lake. She blogs about food and culture on paticheri.com.

Author’s note: My sincere thanks to all those who responded to my call for regional titles, but most especially Sheetal Bhatt, collaborator and chronicler extraordinaire, without whom some of this article couldn’t have been written, Dipali Khandelwal, and Deepa Chauhan.