Memory, like a carefree child in a cottage filled with things, is prone to misplace, hide and invent stuff. For instance in memory, in Arundhati Roy’s debut fiction, the mother had the “unmixable mix” of the infinite tenderness of motherhood and the reckless rage of a suicide bomber. But in real, in her memoir that was globally launched on September 2, there was not a trace of tenderness. There was only the suicide bomber.

In The God Of Small Things (GOST) world, in memory, when her child vomits and his skin grew hot and shiny, the mother loved him more than usual. But in real, in ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me’, when the daughter showed her the hot shiny chickenpox blisters on her stomach, the mother smacked her hard on the cheek for lifting her dress to expose the blisters.

Another memory is of the mother giving the example of Brutus backstabbing Julius Caesar and telling her children that no one could be trusted. And as an extreme example, certain in her heart that her darling son could never be that, she said that even he could possibly grow up to be a Male Chauvinist Pig.

The real mother is no guardian angel, she has the remorseless heart of a policeman who slaps false cases at will on anyone he dislikes. She told the boy on his face that he was not good enough to even be an MCP. “You’re ugly and stupid. If I were you, I’d kill myself.”

Memory lights up a closed railway crossing somewhere in the interiors of Kottayam and inside a sky-blue Plymouth caught in the queue, the mother’s brother, a Rhodes scholar, is heard saying that the children are “millstones” around his neck. Actually, it was she who said it. “You are a millstone around my neck. I should have dumped you in an orphanage the day you were born.”

Memory even gave the mother a lover, Velutha the Untouchable. Fact is, it was the daughter who loved the dark-skinned Velutha but she was too little to take him as her own. “Had I been sixteen years old instead of six, who knows, if I got lucky, he might well have been mine. He was the kindest, most handsome man I had ever seen,” daughter Roy writes in her memoir.

The mother who raged like a storm was charmed by the memory. When asked whether the affair was true, she would ask “Aren’t I not sexy?”

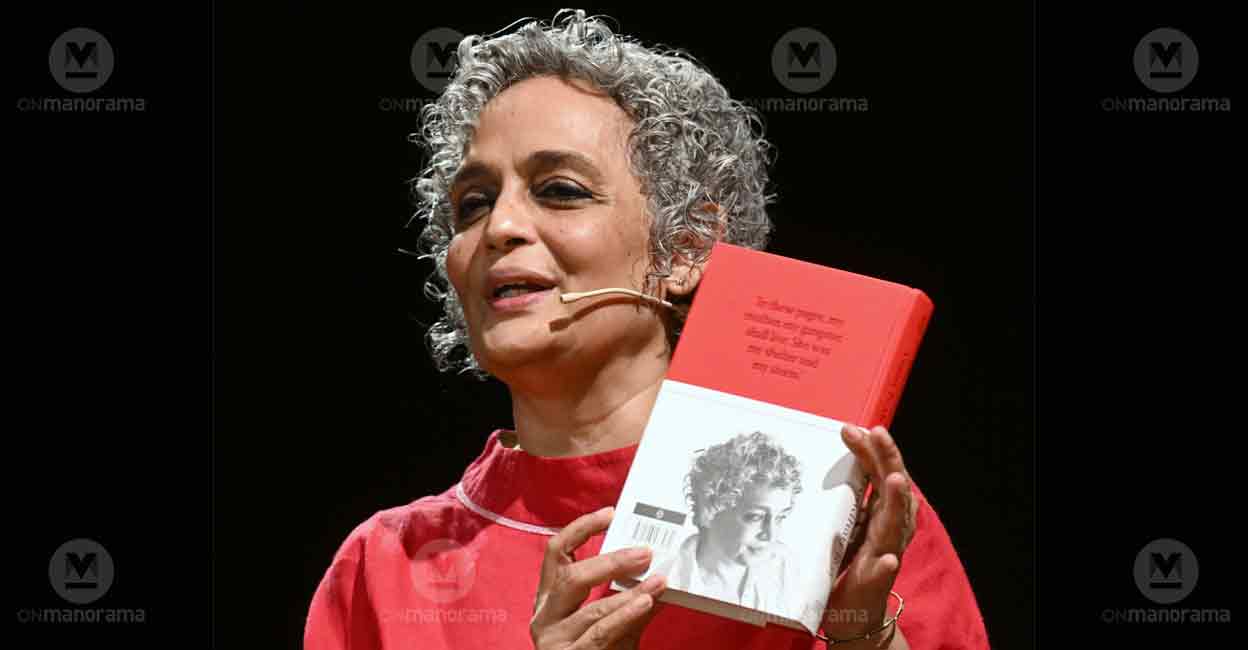

“She believed she was Ammu (the mother in GOST) but she was not,” Arundhati Roy said at the first global public launch of ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me’ at St Teresa’s College, Kochi, on September 2. In a pleasant coincidence, the college hall where the launch took place was called Mother Mary Hall.

Her Mother Mary was so many things at once: genius, eccentric, cruel, bully, radically kind, businesswoman, wild and unpredictable. The daughter had seen her “make space for the whole of herself”, but how was she to write her? “She was like an airport without a runway,” Arundhati said at the launch. How was she to land?

Before she managed, there was yet another line that the daughter crafted so that the memory of the living mother did not drip hot blood. On a blank off-white page at the start of GOST is an haiku-like verse: “For Mary Roy who grew me up/Who taught me to say ‘excuse me’ before interrupting her in Public/Who loved me enough to let me go.

The last line sounded like the ultimate motherly sacrifice. Truth is, the mother did not let her go. The daughter just left. “The tension between us was growing. I single-mindedly wanted to be in a place where I could earn,” daughter Roy said at Mother Mary’s global launch.

“Who loved me enough to let me go” was make-believe. “We settled on a lie. A good one. I crafted it,” Roy says in the book. “She quoted it often, as though it were God’s truth. My brother jokes that it’s the only piece of real fiction in the book,” says Roy.

Arundhati Roy with her brother Lalith Kumar Christopher Roy. Photo: Manorama

Arundhati Roy with her brother Lalith Kumar Christopher Roy. Photo: Manorama

Arundhati Roy with her brother Lalith Kumar Christopher Roy, Prannoy Roy and Radhika Roy. Photo: Manorama

Arundhati Roy talks about her new book ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me’. Photo: Manorama

The brother, Lalith Kumar Christopher Roy (LKC), to whom along with their mother GOST and Mother Mary are dedicated, was at the global launch in Kochi. At the start of Mother Mary Comes to Me Arundhati says: “For LKC/Together we made it to the shore.” The line gives the impression that the siblings, hurled about by the mother-storm, were still lying face down, half dead, not yet up.

When LKC took the stage on September 2, he put their survival in triumphant terms. “She excelled. I succeeded.” LKC is now a seafood exporter who Arundhati says “drives a BMW”. He has his sister’s wispy grey hair but not her vagrant-hearted look. He seemed more like a retiree who regularly goes to school to pick his grandchild.

But the grandpa was the rockstar at the launch. LKC, with an electric guitar strung around his neck, took the mike and sang the 1970s Beatles number ‘Let it Be’ that began ‘When I find myself in times of trouble, Mother Mary comes to me/Speaking words of wisdom, let it be…’

It was a song about Paul McCartney’s soothing-comforting Mother Mary and when LKC delivered the lines, with the intense strain of an ageing rockstar, the Beatles song sounded as a passionate counterpoint to his spurning-crushing Mother Mary who Never Let Anyone Be.

“She had cast a spell on my sister Soo (his pet name for her). Imagine a Booker Prize winner and a world-renowned writer getting rebuked till the end. Soo will retaliate with a joke. I didn’t have the patience to tolerate such behaviour,” LKC said. Mrs Roy was both storm and shelter for the daughter. For the son, she was just the storm.

LKC had a carefree smile that the eternally dismissive Mrs Roy would call ‘inane’. Perhaps his father Micky Roy’s. It was her husband’s giggle that exasperated Mrs Roy the most. Arundhati writes about the irresponsible father: “He told harmless lie, for the hell of it. Because he enjoyed lying. It wasn’t hard for her to catch him out, and when she did, he’d just giggle. She made us look up the word ‘inane’ in the dictionary because it described his giggle perfectly.” By being himself on stage, LKC celebrated the giggle.

There was yet another habit of Micky’s that exasperated her. “Sometimes he blew spit-bubbles. For hours on end.”

On spit-bubbles, memory and reality intersected. The mother in memory also hated the children blowing spit-bubbles as it reminded her of their father.

GOST was hardest on the father. He did not just booze, giggle and blew spit-bubbles. He asked his wife to sleep with a white man so that he could keep his job. Daddy-pimp was the invention of a daughter who had developed fangs for her absentee father.

Mother Mary resurrects Micky from the pit of indignity that his vindictive daughter’s fiction had dug up for him. He is still addicted to booze, still a failure, the Nothing Man, filthy and still a hopeless giggler. But he had an impish twinkle that fascinated the grown-up daughter.

“Ta-ta then. Bye-O. Don’t be good,” was his parting shot to his children the day he met them after 22 years and emptied them of the pittance in their wallets. Once he was handsome but now he was a “frail hunchback on toothpick legs”. “We sat on the hotel bed with its ash-smeared sheets, my brother and I, a pair of chumps. Utterly charmed, and relieved of all our money,” Arundhati writes in Mother Mary.

Much later, in a curious turn of fate, both the father and mother enter life support, simultaneously. The Nothing Man in Kolkata and the Contemptuous Queen in Kerala. Arundhati had to leave her father to care for her mother. “I said goodbye to him and left for Kerala. I knew I would never see that beloved rogue again,” Arundhati writes.

Before she could enter Mrs Roy’s room at a Kottayam hospital, Micky died.