August 2025

August 2025

When Iliana Lilienthal asked—well, told—David Butler she wanted a select batch of his pastels for Lilienthal Gallery’s Deconstructing Landscapes exhibition, he was caught off guard. She’d spotted them in his South Knoxville home during a party he and husband Ted Smith were hosting. David hadn’t created them with the outside world in mind.

Each one depicts the Great Smoky Mountains, a subject that never really sits still. The flutter of leaves, the shifting play of light and shadow, the eternal mini-drama of a mountain creek … David attempts the impossible task of pinning down the fleeting energy of it all.

Iliana has impeccable taste and a mind like a jeweler’s cut when it comes to curation. David agreed to share his works, but he’s quick to admit he feels like an imposter. It’s the first time he has appeared in a major exhibition. He was one of just three regional artists included (we profiled Gary Heatherly last month), alongside others from Oregon to Israel.

A little imposter syndrome is understandable. David has been surrounded, literally, by some of the best art in the world his entire career. Now, 20 months into retirement from his post as longtime executive director of the Knoxville Museum of Art, he’s still settling into what comes next.

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

Home

David and Ted’s 1969 rancher, all brick and glass with a tiffany-blue front door, is couched in river rock and shade gardens. Inside, every surface holds a piece of art.

“Almost everything we have in the house is by an artist who is a friend of ours or at least someone we know,” David says. “When people give me art, I always think of that person. And I always remember who gave me plants.”

Walking room to room, he narrates the origin stories: a wedding gift, a painting of their Wichita home, a reminder of an old friend. There’s a plein air piece by Robert Felker of KMA at sunrise or sunset, it’s hard to tell which, Victorian houses across the street reflected on its windows. A retirement gift from the Guild, Butler smiles: “I think the sun’s kind of me leaving the museum. It makes me happy.”

His own art and Ted’s photography mix into the display. Downstairs, his studio opens with floor-to-ceiling windows onto the greenery of high summer. “The light coming through here is so beautiful at different times of the day,” he says. A magnolia tree they planted just a decade ago now towers behind the house, framed by oakleaf hydrangeas and accented by coleus’ swizzling of magenta and lime.

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

Making Space

These days, David mostly works in pastels, with a side exploration of watercolor after a workshop with Jered Sprecher at Arrowmont last year. “Not much to show for it, I’m afraid,” he laughs. “Watercolor is hard, and I don’t like to do things I’m not good at. But there are occasional flickers of maybe I could do this.”

Routine, he admits, is harder. “When you have lots of time, you never feel that sense of urgency. Before, if I had a long weekend, I’d lock myself down here and get stuff done. Now it’s much more, well, we’ll get there. I could create a schedule, but I also kind of rebel against that.”

Even though he spent decades in museums, creating art feels entirely different. “Although I was around art all the time, you’re using a different side of your brain. When I sit down and really get working, the world just disappears—time passes, I don’t get hungry. But it takes a while to get into that space.”

Much of his work is tied to memory: happy places he can revisit through art. “You remember how you felt in that spot, and there’s a lot of that encoded if you do it well.”

David Butler with Gay Lyons on a trip to Paris last spring

David Butler with Gay Lyons on a trip to Paris last spring

David on his way … somewhere!

David on his way … somewhere!

Travel & Time

The sensory experience of travel feeds that same part of his brain. David and Ted marked his retirement with a trip to New Zealand and Australia. Genoa comes this fall, the Aegean this winter, and a river cruise in Egypt next year. They try, he says, to be mindful of visiting places where tourism is welcomed. “Everything is so crowded, and some places don’t want more people. Like, where can we be helpful? Where do they want us? And that’s fewer and fewer places.”

Ironically, David rarely spends more than 45 minutes at other city’s art museums, no matter how large. “I’m a bad museum-goer,” he says. “All I can see is how the labels are made, what the lighting is like. Plus, you can only soak up so much.”

The Smokies are an annual pilgrimage. The mountains are a muse in his work: layers of blue ridges and water flowing glasslike over rocks. He collects rocks and minerals, too, each one with a story. He points to a stone given to him after the passing of his friend John Thomas last summer.

On a shelf nearby sits a classic still-life of a fruit bowl that he painted at age six. “So 65 years ago, and we’ve somehow hung onto it,” he says. “It wasn’t Rembrandt, but I could draw fairly competently for a 6-year-old.”

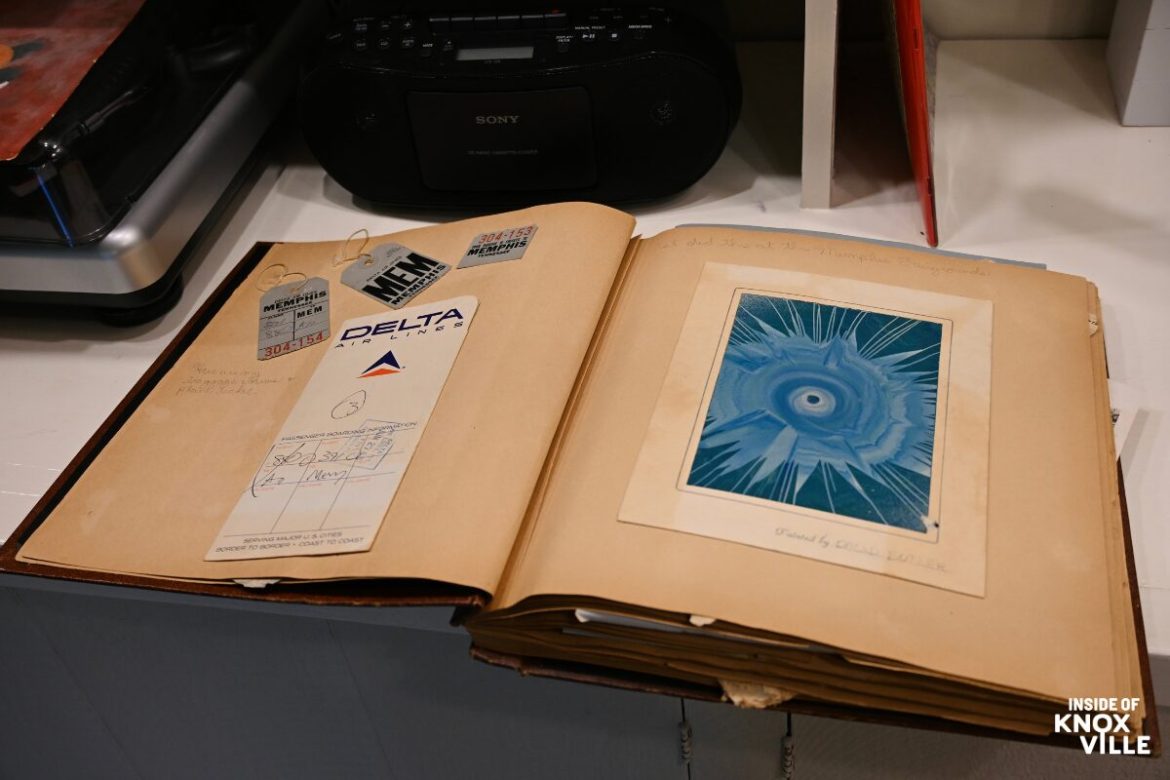

Beneath it lies a scrapbook unearthed from his mother’s house. Scrawled on the first page in child’s pencil handwriting: The Great ’68 Trip. It documents his first plane ride, from Florida to Memphis. “You would have thought I was going around the world,” he says. “But when you’ve never gone anywhere, anywhere is exciting. I got kind of weak, looking at it.”

At 18, he spent a year abroad in Italy. “And I remember thinking, ‘Oh my God, I discovered all of this.’ There’s no one more full of themselves than a teenager. But I can still remember that feeling.”

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

Memory

It’s funny sometimes to realize we’ve always been who we are. Looking around his studio—at finished and half-finished canvases, books, artifacts and at least one Leaning Tower of Pisa parmesan cheese dispenser—David shrugs: “You get to a certain age and realize, oh gosh, there’s probably not going to be a museum dedicated to me.”

Maybe not. But all of us build our own museums through the objects we keep close, the people we love, the places we return to in memory.

David told me Venice, a city he once adored, is now too crowded to revisit. But in his memory it still exists as he experienced it, preserved in the same way he memorializes mountain creeks and the bowl of fruit he sat in front of at age 6, through the medium of art.

In one of my favorite books, Invisible Cities, author Italo Calvino imagines Marco Polo describing Venice through dozens of dreamlike versions of itself. At one point Polo admits: “Memory’s images, once they are fixed in words, are erased. Perhaps I am afraid of losing Venice all at once if I speak of it, or perhaps, speaking of other cities, I have already lost it, little by little.”

Italo reminds us that memory is slippery. The moment you try to translate an experience into words—or into art—you’ve already changed it. The original image fades, and what remains is a kind of imperfect facsimile. Still, that replica matters. It’s the thing that keeps the memory alive. “Memory is redundant,” Italo says, “it repeats signs so that the city can begin to exist.”

David Butler, Deconstructing Landscapes, Lilienthal Gallery, 23 Emory Place, Knoxville, July 2025

David Butler, Deconstructing Landscapes, Lilienthal Gallery, 23 Emory Place, Knoxville, July 2025

“Deconstructing Landscapes” is on view at Lilienthal Gallery (23 Emory Place) through mid-October. Hours are Wed-Sun 12-5 p.m. Learn more at the website here; you can also follow Lilienthal on Facebook and Instagram.