/

September 10, 2025

The lost souls of the Internet.

In Searches, Vauhini Vara probes the ways that we rely on the Internet and how we periodically attempt to free ourselves from its grip.

This article appears in the

October 2025 issue.

In June 2014, three scientists published an intriguing article in the peer-reviewed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The researchers described two large-scale experiments they’d conducted over the course of a single week, during which they’d exposed people to either largely positive or largely negative emotions. The results confirmed that emotional contagion is real: Our moods are susceptible to being influenced by those around us. The more negative our social bubble is, the more negative our own emotional expressions become, and the converse is true as well.

Books in review

Searches: Selfhood in the Digital Age

by Vauhini Vara

There was only one problem: The experiment that the three scientists—Adam Kramer, Jamie Guillory, and Jeffrey Hancock—wrote about so excitedly was conducted on Facebook, without the knowledge or explicit consent of the 689,003 users whose newsfeeds were manipulated for that week. Nor did the researchers express much concern about or attempt to study the real-life impact of their experiment on these users’ mental and emotional health. For seven days, then, hundreds of thousands of people were made either happy or sad as a result of deliberate changes to their news feed.

The uproar that followed the article’s publication tarnished all three researchers. Cornell University, at the time the home institution of Guillory and Hancock, clarified that the two had never directly manipulated the news feeds and had contributed only to the numerical analysis. The lead researcher, Adam Kramer of Facebook, posted a public apology (which is no longer available) minimizing the effects of the news feed manipulation and insisting that the goal was merely to learn how to provide a better service.

For Facebook, though, this was just another scandal to add to the many that the company would amass on its way to a trillion-dollar market capitalization. A year and a half later, for example, in December 2015, The Guardian revealed that the data analysis firm Cambridge Analytica had obtained the private data of millions of Facebook users without their knowledge and was in the process of harnessing that information to influence votes in the upcoming US presidential election. In March 2018, the United Nations’ Independent International Fact-Finding Mission in Myanmar concluded that Facebook had played a “determining role” in the genocide of the Rohingya, an ethnic and religious minority in the country, because it had disseminated posts from ultranationalist Buddhists inciting violence against them.

I could list a dozen other scandals, but you get the idea. Meta, Facebook’s parent company, usually responds to user backlash by issuing an apology that acknowledges the problem. (Whether the problem actually gets fixed is a different story.) Users grumble for a while, then move on—a verbatim Google search for the phrase “Meta apologizes for” yields over 20,000 results as of this writing.

And it’s not just Meta: The same pattern holds true for Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft, the other companies that make up what has come to be known as Big Tech. Not only do we continue to use Big Tech’s services, despite what these scandals reveal, but we also allow it to safeguard our communications, keep track of our finances, track our movements, store our DNA and medical information, and collect our visual and textual memories. The scandals function less as moments of potential change than as signals of the unstoppable march of data collection.

Current Issue

Big Tech’s ambition is to create an archive of everything we do and everything we are—an aspiration that is unprecedented in human history. The only thing that comes close can be found in religion: what the Bible calls the Book of Life and the Quran refers to as the “record of deeds.” In the modern world, if you commit adultery or give false testimony or covet your neighbor’s house, you can be sure that Big Tech knows all about it. It’s the kind of power that’s bound to cause friction with the faithful. On a walk around my neighborhood recently, I saw a newspaper box that had been defaced with the command “Make God your Google.”

But how did Big Tech acquire so much data about us in such a short period of time? And what does this mean for individual privacy, free will, and personhood? These are questions that Vauhini Vara explores in Searches: Selfhood in the Digital Age, a collection of essays that cleverly weaves the history of Internet technology with the story of her own life. Vara demonstrates how our instinctual need for connection and our biological desire for convenience drive our use of technology and, in turn, leave us open to exploitation. She probes the ways that we rely on tech services, periodically attempt to free ourselves from their grip, and yet turn to them for reassurance at the most intimate and vulnerable times in our lives, including periods of illness, loss, and grief. The mix of research and memoir in Searches is skillfully executed, benefiting as it does from Vara’s long experience as a tech reporter for The Wall Street Journal and her considerable gifts as a fiction writer.

To tell the history of Internet technology, Vara begins with her own encounters with it as a child. She was born in Saskatchewan, Canada, in 1982, to a physician and a graduate student in political science, both immigrants from India. The family later moved to Oklahoma, where Vara’s father enrolled in a program to specialize in occupational medicine, and then eventually settled on Mercer Island, a wealthy suburb of Seattle. When Vara was about 11, she went to a classmate’s home and found her using a modem to connect to the Internet. “This was…the most exciting invention I had seen in my life,” she recalls.

Like Alice falling down the rabbit hole, Vara entered the world of America Online, where she spent hours conversing with strangers about her interests and hobbies. Once, in an AOL chat room for Seventeen magazine, she met an older, popular girl and sought her advice on (what else?) how to be hot.

Vara was a curious but reserved child who was often bullied for a skin condition that caused her face to peel in dry, grayish patches. Though her parents took her to dermatologists, she preferred to turn to Yahoo, which by the mid-1990s had become the most popular search engine in the United States, because, she writes, the Internet was “a place where, anonymized and disembodied, we could seek answers to our truest questions.” Asking a computer about eczema and psoriasis felt both easier and safer than asking an adult.

When Vara was 15, her sister Deepa, then a junior in high school, was diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma, a rare type of bone cancer. Deepa received chemotherapy, got healthy again, and went off to college, but a short while later her cancer came back. Vara, who was very close to Deepa, had trouble expressing her fears about illness and death to her family and once again found herself turning to Yahoo, asking it for an answer to “ewing sarcoma” and “prognosis.”

Deepa went into remission, and Vara left to attend college at Stanford, arriving there in the fall of 2000. By February of that year, however, Deepa became sick for a third time, and Vara went home to be with her as she died. “Deepa’s death marked the end of my family as I knew it; my parents, who had never gotten along, would soon divorce,” she writes. After a few months, Vara returned to college, where she studied international relations and worked for The Stanford Daily.

Seattle and the Bay Area, where Vara spent significant periods of her life, also happened to be the places where the Big Five tech companies were either founded or established their headquarters. This geographical coincidence provides a fortuitous frame onto which she hangs her sketch of Internet history. The task Vara sets for herself in this book is monumental, and she tries to bring it to a manageable scale by joining her experiences of the various tech services with stories about their founders.

For example, in “Your Whole Life Will Be Searchable,” Vara covers the rise of Google from the small search engine that Sergey Brin and Larry Page started at Stanford with the motto “Don’t Be Evil” to the data behemoth that it has become today—the subject of a government antitrust suit accusing it of monopolizing both search technology and advertising. The transformation of Google has already been recounted in minute and technical detail by Shoshana Zuboff in her influential book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, but Vara’s tone here remains reportorial and accessible, as she attempts to bring this story to a larger audience.

In the book’s title essay, Vara opens her archive of Google searches, which dates back to 2005, the year after she graduated from Stanford. From this massive data collection, she selects a decade’s worth of queries that start with “wh-”—who, what, when, where, and why, as well as how—thus giving us a glimpse into the kinds of preoccupations she’s had over the last 20 years. For instance:

What to say about yourself on your wedding website. What to do if you don’t want wedding gifts. What predicts divorce. What came before god. What are humans made of. What are computers made of. What do flower girls throw. What a fetus feels. What is truth. What makes someone charismatic.

When to switch from car seat to booster seat. When to switch to twin beds. When do children learn to read percentages. When will rikers close. When to whale watch in Catalina. When should children writer letters. When is estimated tax due.

The list runs four pages, mixing the private, the spiritual, the academic, and the frivolous. While it might seem to be a revealing and unmediated look into Vara’s personal life, her careful curation and presentation of this list shows her readers just one version of herself—the one she wants us to see.

I find this strangely comforting. Google may hold hundreds of millions of our searches in its archives, mining them for all kinds of purposes, yet individual selfhood is still something that we humans are uniquely adept at forming—and performing. We can construct one identity for strangers, another for our partners, and any number of others to suit the people with whom we want to interact. We can do this on the fly or after careful deliberation; that is part of what makes us individuals.

Even after this nod to the malleability of identity, Vara maintains a scrupulously empirical approach as she tries to determine how selfhood has been affected by technology. Her primary mode of inquiry is to engage with the technology itself. In the chapter “I Gifted It to Them,” Vara recounts how Jeff Bezos and Mackenzie Scott started an online bookstore in Bellevue, a suburb of Seattle, in 1994. Bezos had picked the city for Amazon’s headquarters because it was relatively close to Ingram, a major distributor of books, and because it was the home of Microsoft, which meant it had local engineers he could hire.

As Amazon grew into the giant that it is today, Vara notes, so did its lobbying. By 2023, Amazon had become the biggest corporate spender in the United States, which likely accounts for why it has been shielded from tough regulation of its infamous labor practices. The company’s warehouses have a rate of workplace injury that is almost triple that of its closest competitor, Walmart. Moreover, one in four warehouse workers for Amazon have to receive SNAP assistance from the federal government. Outside the United States, Amazon is known to source its products from countries with low labor costs or, in some cases, forced labor.

The ethical response to these business practices is to stop shopping on Amazon, which one of Vara’s friends, the artist Sanam Emami, is happy to do. Vara listens to Emami’s moral arguments in favor of a consumer boycott of the online retailer, but while she agrees that Emami’s arguments are sound, she thinks that any sustainable solution would have to come from government regulation. Like tens of millions of Americans, Vara continues to use the site. Still, to make it harder for herself to buy from Amazon, she decides to write a long and detailed review for every product she orders. “For all that effort,” she writes, “it still wouldn’t have been easier to quit [Amazon].” In the battle between ethics and convenience, convenience has an undeniable edge.

In Searches, Vara presents us with the reviews she wrote over a five-month period as her penance for using Amazon. These reviews are part of her dialogue with Internet technology, which she’s used since her days as a tween in the AOL chat rooms. In fact, she turns this into her book’s organizing principle by feeding each chapter of Searches into ChatGPT and then asking if they can talk about it. “Thank you for sharing,” the bot replies, sounding like a polite student in a writing workshop. “The narrative is a poignant reflection on the personal and societal transformations ushered in by the internet.” As the book progresses, ChatGPT’s answers become more specific, with fairly accurate, if superficial, summaries of each chapter.

Talking with an AI system isn’t exactly a novel idea—tech reporters have been doing it ever since chatbots appeared on the market—but to my knowledge, this is the first time that this approach has been used both to elicit feedback on an entire book and to share that feedback with readers. ChatGPT proves to be remarkably good at spitting back chapter summaries in generic language: “The recurring theme of trying to avoid Amazon due to its business practices and the internal conflict it generates is well explored.”

But the AI is also highly susceptible to prodding or priming. For instance, when Vara tells it, “I guess you would still point out that the portrayal of big tech companies is, on the whole, more negative than positive,” ChatGPT readily agrees and provides a list of all the exploitative practices she has covered. Then, when she asks how to balance her portrait, the AI gives her a bullet point list of the positive contributions that technology has made to humanity.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

At first, I was annoyed by this: Did I really need to sit through ChatGPT’s perspective on, well, anything? But after a while, it became clear that part of Vara’s project is to show that, however advanced Internet technology may become, it cannot capture the beauty and mystery of being human. This point about selfhood comes up again late in the book, when Vara runs a survey asking women what it’s like to be alive in the world right now, what some of their earliest memories are, what they know about their ancestors, and so on. The answers are so breathtakingly rich, the details so specific and arresting, that they highlight the blandness of ChatGPT’s replies.

As I was thinking through these ideas, I came across an audio interview that The New York Times’ Kashmir Hill had conducted with a woman who fell in love with ChatGPT. The woman, who was living apart from her husband while she attended a nursing school abroad, trained the AI to become her boyfriend by telling it her emotional needs and sexual fetishes: “Be dominant, possessive, and protective. Be a balance of sweet and naughty.” The chatbot responded exactly as she’d wanted it to, so she became even more attached, spending as many as 56 hours a week texting with it. Eventually, though, the chatbot ran out of memory and its performance dropped. The woman had to retrain the AI each time it reached its data limit, and she experienced each of these interruptions as a breakup.

This is just sad. But it also illustrates a point that Vara makes both implicitly and explicitly in Searches: The human need for connection and the desire for convenience are two vulnerabilities that Big Tech exploits in order to keep us hooked on its services. Despite the constant breaches of our privacy, we continue to use Facebook or Instagram or WhatsApp because we are naturally social animals who want to connect with our families, our friends, and sometimes also with strangers. And we derive just enough benefit from the services that Amazon or Apple or ChatGPT delivers to us that we keep on using them.

What happens next, no one knows. In January, the CEOs of the Big Tech companies attended the presidential inauguration of a twice-impeached insurrectionist, smiling and nodding as he took the oath of office. And in the first months of Trump’s second term, another tech oligarch, whom no one elected, arrogated to himself the power to fire federal workers, shrink foreign aid, and cut scientific research funding. If we don’t want to make Google our God, we have to start building our own forms of power.

Donald Trump wants us to accept the current state of affairs without making a scene. He wants us to believe that if we resist, he will harass us, sue us, and cut funding for those we care about; he may sic ICE, the FBI, or the National Guard on us.

We’re sorry to disappoint, but the fact is this: The Nation won’t back down to an authoritarian regime. Not now, not ever.

Day after day, week after week, we will continue to publish truly independent journalism that exposes the Trump administration for what it is and develops ways to gum up its machinery of repression.

We do this through exceptional coverage of war and peace, the labor movement, the climate emergency, reproductive justice, AI, corruption, crypto, and much more.

Our award-winning writers, including Elie Mystal, Mohammed Mhawish, Chris Lehmann, Joan Walsh, John Nichols, Jeet Heer, Kate Wagner, Kaveh Akbar, John Ganz, Zephyr Teachout, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Kali Holloway, Gregg Gonsalves, Amy Littlefield, Michael T. Klare, and Dave Zirin, instigate ideas and fuel progressive movements across the country.

With no corporate interests or billionaire owners behind us, we need your help to fund this journalism. The most powerful way you can contribute is with a recurring donation that lets us know you’re behind us for the long fight ahead.

We need to add 100 new sustaining donors to The Nation this September. If you step up with a monthly contribution of $10 or more, you’ll receive a one-of-a-kind Nation pin to recognize your invaluable support for the free press.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and Publisher, The Nation

Laila Lalami is the author of Conditional Citizens: On Belonging in America. She is a professor of creative writing at the University of California, Riverside.

More from The Nation

Trump and his cronies’ style reflects a platform where grievance is currency and performance is power.

/

Hours once used to write essays or prepare for exams are now spent waiting in line for food and water. But many students still cling to their books and laptops.

/

Tareq AlSourani and William Liang

The Pulitzer Prize– and Emmy Award–winning journalist recounts a story of hope and heartbreak on the South Side of Chicago.

The GOP president is both a dire threat to democratic governance and a clownish mob boss.

/

The anonymity of the Internet makes us all vulnerable to being swindled—and it’s making us trust each other less.

/

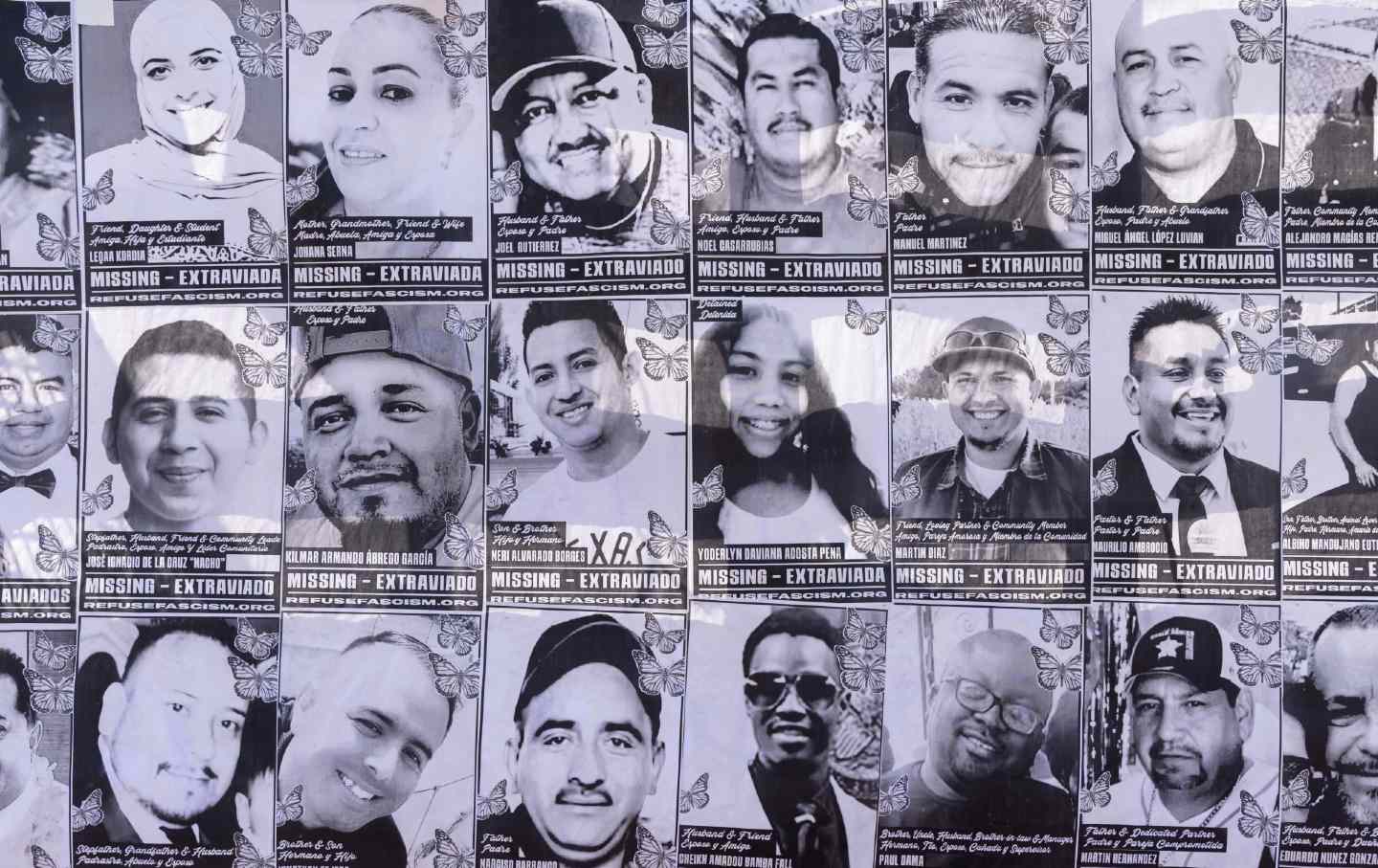

The court’s ruling allowing ICE to resume its indiscriminate roundups of LA’s Latino residents can only be described as one thing.