Farmers’ Costs Are Up

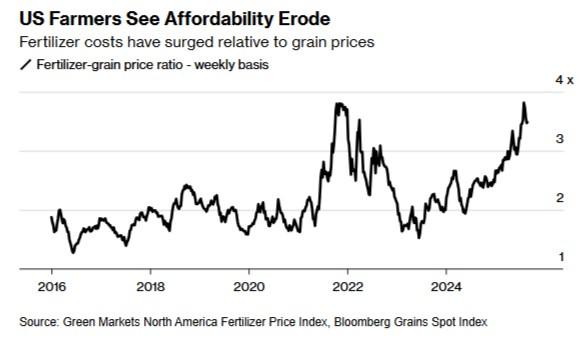

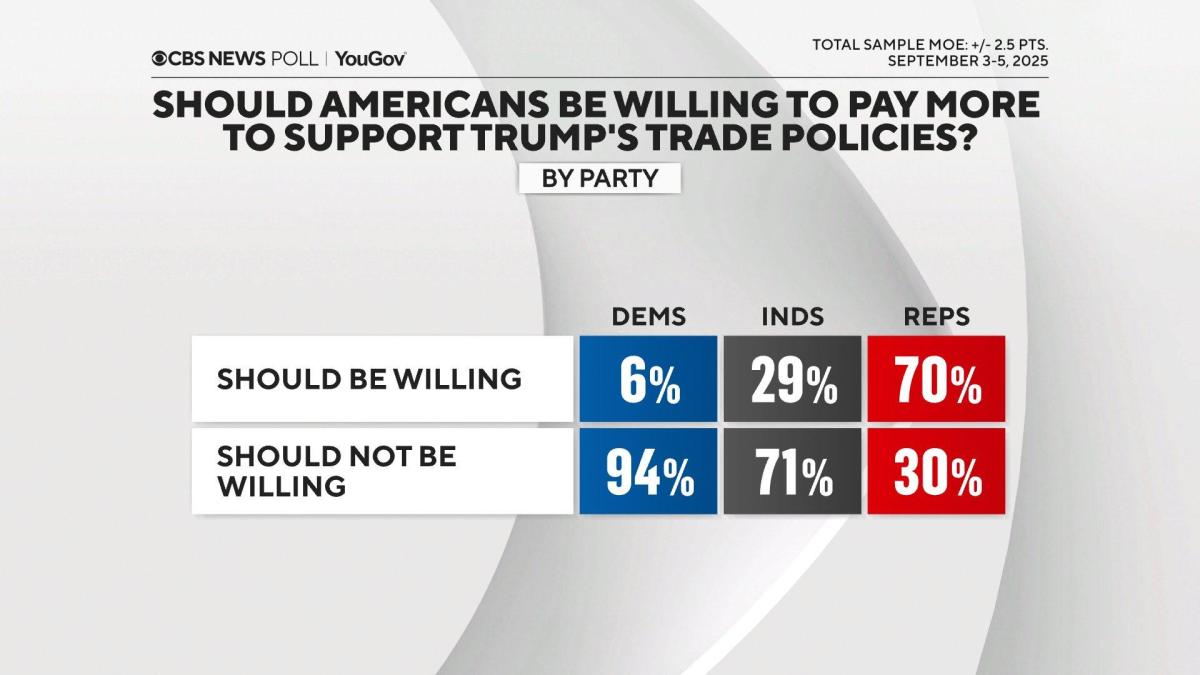

Input costs and trade policy are the most obvious places to start. As Bloomberg reported late last month, new U.S. tariffs and related uncertainty have caused domestic fertilizer prices to spike:

“Tariff uncertainty has certainly been a factor in driving fertilizer prices higher, even with exemptions carved out for most fertilizers,” Daniel Cole, a Bloomberg Intelligence analyst, said by email. While other issues — including China’s decision to curb some exports and recent production outages in the Middle East — have also fueled the rally, the fertilizer industry “has largely been in a state of confusion since the tariff rollout.”… Tariffs have constrained shipments of phosphate and potash to the US, and are expected to “remain subdued” because of tariffs, producer Mosaic Co. said earlier this month.

As you can see in the chart below, U.S. fertilizer prices are still below where they were in 2021-22, but they’ve consistently climbed since January to levels well above where they were before 2021:

As Bloomberg notes, trade policy isn’t the only thing going on here, but it surely deserves much of the blame. As Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa recently opined on Twitter, in fact, the “fastest relief for farmers” facing relatively high fertilizer costs would be “lowering duties on fertilizer imports.”

American farmers’ cost pressures also extend beyond fertilizer. Farm machinery and equipment, for example, have also been hit by tariffs in several ways. Most obviously, tariffs on imports of foreign-made products are leading to price hikes here:

“All of our competitors and us have certain products that are going to be more expensive,” said Eric Hansotia, CEO of tractor maker Agco, which has recently announced some price hikes in North America.

As the Wall Street Journal just documented, imported farm equipment (and other machinery) is also getting hit by complicated new rules for U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs:

The effective tariff facing exporters now varies depending on a product’s metal content. For a machine worth $1 million with a 20% steel content, the rate would be 50% of $200,000 and 15% of the rest, resulting in a $220,000 levy per machine—or a 22% tariff. The U.S. has said it would review the metals tariff list every four months, adding to the uncertainty.

And the tariffs’ complexity adds to the costs that imported farm machinery now faces:

[European producer] Krone says it must now document the steel and aluminum content of the 15,000 parts that make up its Big X forage harvester, for instance. Between 10% and 15% of the company’s farming-equipment sales go to North America. Even companies whose products aren’t subject to the steel tariffs can get ensnared. …

Take valves, a commodity device to regulate the flow of liquid in a machine. Valves aren’t on the expanded steel tariff list but are used in injection-molding machines. Since these machines are on the list, their manufacturers must now obtain from their suppliers information about the steel content of their valves—where it was bought, at what price, and where the metal was melted and poured.

The Journal goes on to note that companies ensnared by this mess aren’t planning to bring much manufacturing capacity into the United States due to “a dearth of skilled labor and high production costs.” This includes, the paper explains elsewhere, Agco—the third largest farm-equipment seller in the United States, with production here and abroad (mainly Europe). Because the company doesn’t sell enough here to justify onshoring more production, it will simply sell tractors in the U.S. market with the “necessary” price hikes—new tariff costs that will likely deter any U.S. expansion and weigh on American farmers.

The pain also extends to the United States’ own John Deere. As the Journal notes, for example, about 20 percent of the company’s German output is exported to the U.S., and it has no intention of onshoring that production and will instead simply eat or pass on the tariffs. The company also has a large U.S. manufacturing footprint (30,000 employees at 60 facilities nationwide), which is also being hit by tariffs—and higher prices for U.S. goods—on steel, aluminum, copper, engines, and other key inputs. No surprise, then, that Deere recently reported that it’s paying hundreds of millions of dollars in additional tariff-related costs—costs that will be borne by the firm’s workers (hence, recent U.S. layoffs), shareholders, and customers (i.e., American farmers).

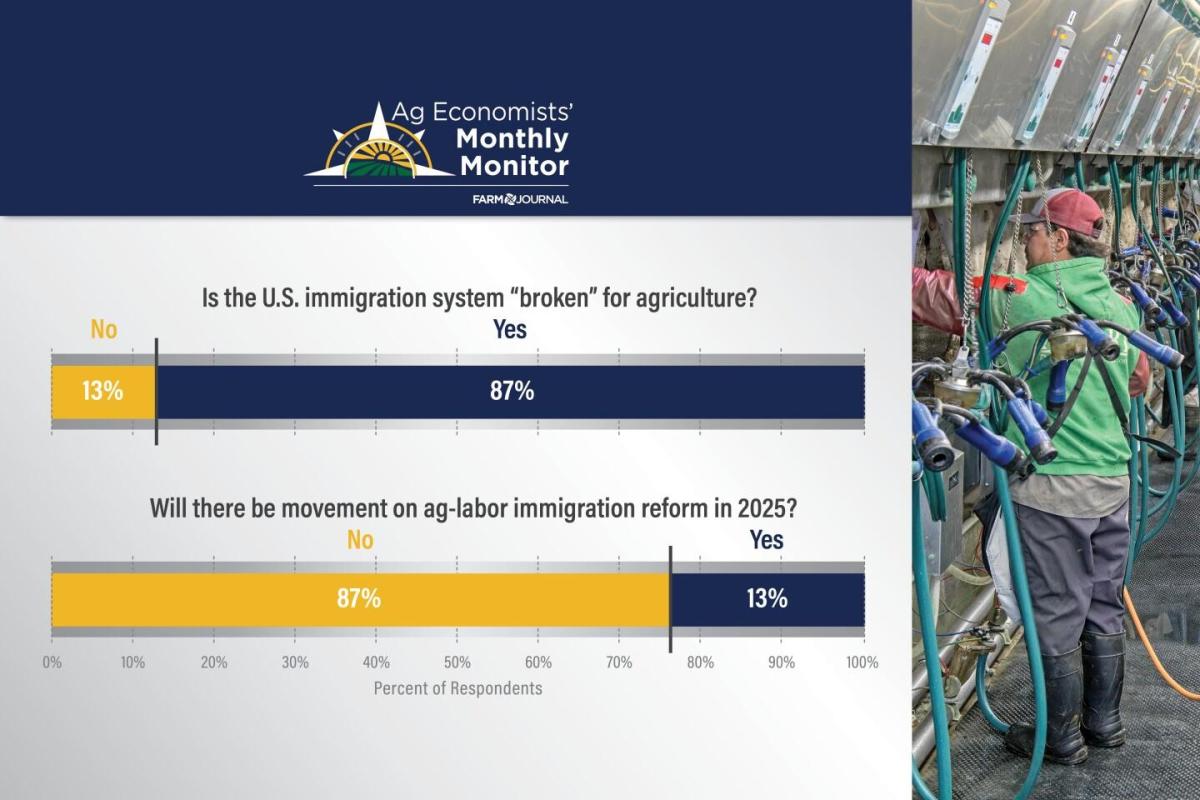

Finally, U.S. immigration policy is pressuring farmers’ labor costs. As CNN recently reported, for example, farmers across the country are struggling to find workers because widescale deportation efforts have ensnared many immigrant laborers and scared off many others—both illegal and legal. Given the large share of immigrants working in agriculture—along with native-born workers’ distaste for the work—the result of the administration’s focus on immigrant farm workers is higher labor costs for the remaining workers and/or simply less production. No wonder, then, that “in the latest Farm Journal Ag Economists’ Monthly Monitor, 87 percent of economists said the U.S. immigration system is broken for agriculture”—with little hope for reform any time soon.

And Their Prices Are Down

American farmers might be able to weather (pun!) these higher costs if they were able to charge even higher prices for the stuff they grow, but as of early August prices were down too: “A benchmark for corn, soybean and wheat prices has fallen to its lowest levels since the height of pandemic lockdowns amid ample supplies globally, cutting into farm revenues.” (Corn prices have rebounded a bit since then, but remain well below where they were in February.)

Government policy again deserves much of the blame, and trade is again the place to start. Trump’s tariffs and related antagonism have caused buyers abroad to turn away from U.S. agricultural products, meaning fewer sales abroad for export-dependent farmers and, given the glut of unsold crops, lower prices at home. As Bloomberg recently reported, the biggest problem here is undoubtedly China:

America’s farmers are expecting bumper crops this fall, but they’ve got little idea of where all the supplies will go. China, historically the biggest buyer of US soybeans, hasn’t inked a deal for a single cargo from this year’s harvest, which starts next month. Blowback from President Donald Trump’s trade war has served to further chill the administration’s already icy relationship with the Asian country.

Since then, Reuters reports, Chinese buyers finally did book some U.S. soybeans, but sales volumes remain billions of dollars short of where they were just last year.

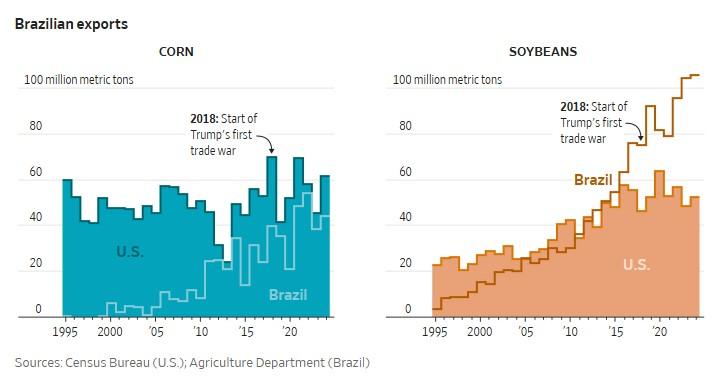

Readers of Capitolism will surely recall that China turned away from U.S. soy during Trump’s first term, but the trend has accelerated since Trump returned to office. Bloomberg adds elsewhere, in fact, that Chinese purchasers are building a historically large stockpile of non-U.S. beans—Chinese and mainly Brazilian imports—to be “better prepared” for a winter with few U.S. soybeans. The result would be devastating for American farmers who have plowed (pun!) into the crop in recent years.

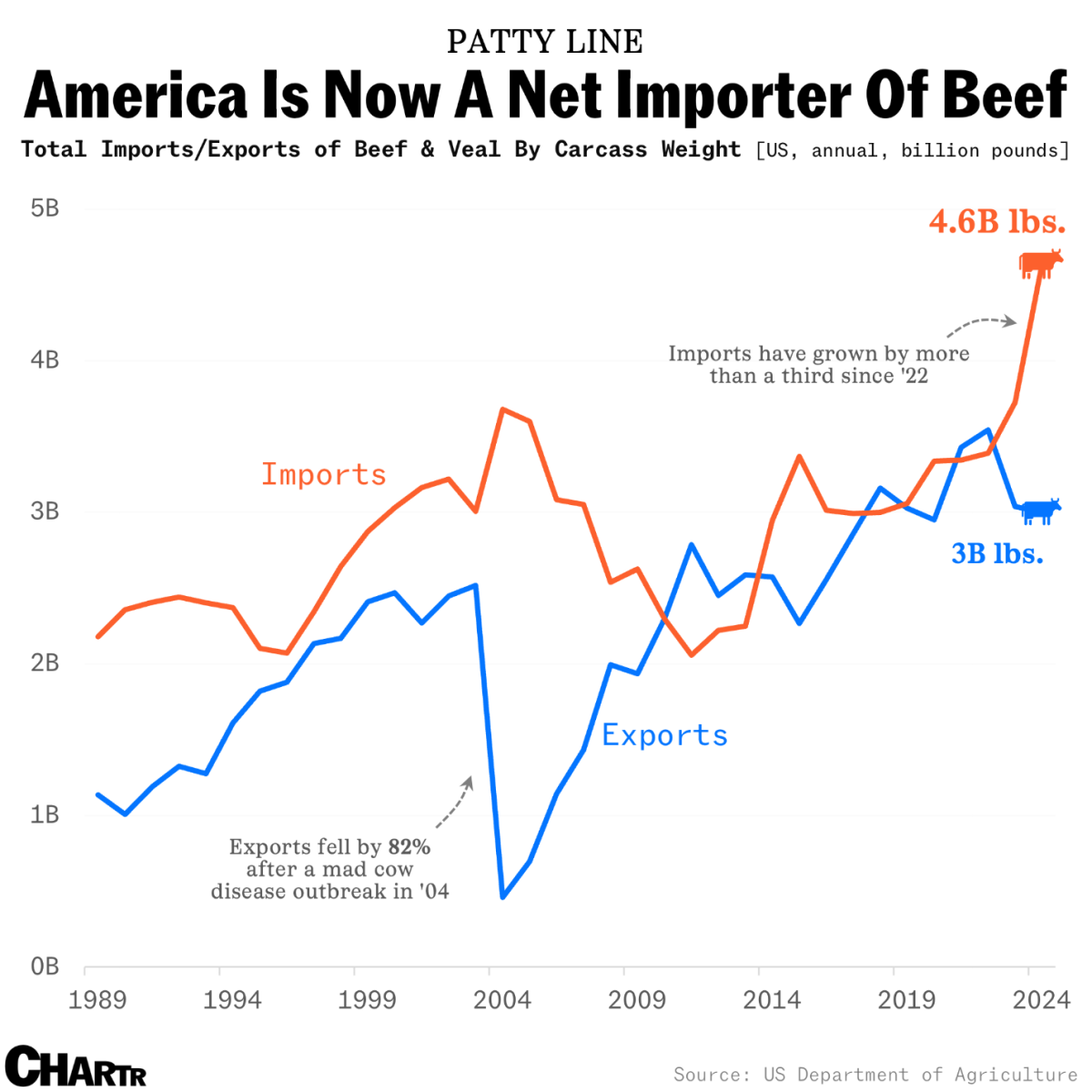

Farmers’ trade problems aren’t, however, just about soybean exports. News reports show, for example, that U.S. exporters of alfalfa, beef and pork, almonds, dairy, cotton, sorghum, and other products have all taken hits since Trump’s tariff mayhem began in February. Exports to China are typically the biggest losses in these cases, too, but other nations are also turning away from American agriculture. Overall, the USDA in May projected softening exports and a widening “agricultural trade deficit” due to tariffs and trade tensions. (The latest report showed exports remaining basically flat for 2025-26 but—in cringeworthy fashion—avoided controversy by simply removing the commentary section entirely.)

Another trade policy problem is that the U.S. has effectively given up on broad, comprehensive free trade agreements that typically boost U.S. farm exports. Commenting on USDA’s projections, for example, the American Farm Bureau explained that “foreign buyers are turning to lower-cost suppliers like Brazil and Argentina,” and that the United States thus needs “to pursue new trade agreements and strengthen existing ones to expand export opportunities.” The CEO of the National Corn Growers Association put it even more bluntly: “The United States hasn’t secured a new trade deal with a major partner in over a decade.”

As the Farm Bureau statement indicates, foreign competition in important markets abroad is indeed a big challenge for American farmers—-and Brazil looms large in this respect, with ever-escalating exports as U.S. sales abroad stagnate:

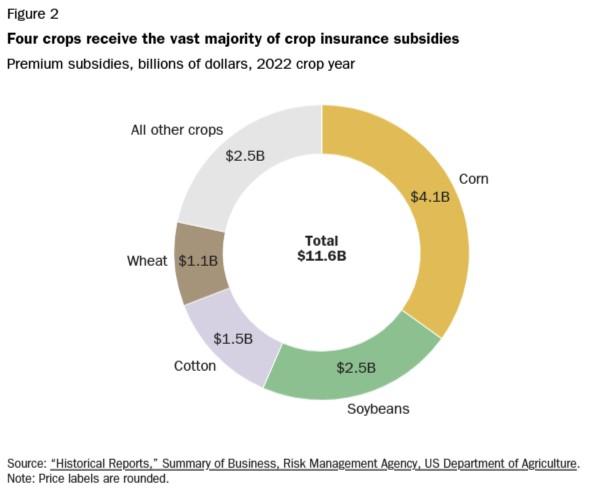

The other big problem is U.S. subsidies and renewable fuel mandates that encourage the overproduction of certain crops, especially corn and soy. As we’ve discussed repeatedly, U.S. farm payments have long encouraged farmers to grow certain products (corn, dairy, etc.) that get extra-special government treatment, thus resulting in periodic gluts when state-encouraged supply outstrips demand. As my Cato colleague Paul Best documented in 2024, government crop insurance is particularly bad in this regard, with one Iowa farmer estimating that the “vast majority” of all U.S. planting decisions depend on “how much money is guaranteed through subsidized crop insurance,” thus creating a highly centralized production system:

“Government would like farmers to grow certain commodities, the big players—corn, wheat, soybeans,” [Iowa farmer Gabe] Brown said. “By offering those incentives, the farmer’s going to go, ‘Well, I can make the most money planting corn, because I’m guaranteed this amount of money.’ Farmers know as long as they keep their expenses below that payment price, they’re going to make money, so it incentivizes farmers to plant those monocultures year after year.”

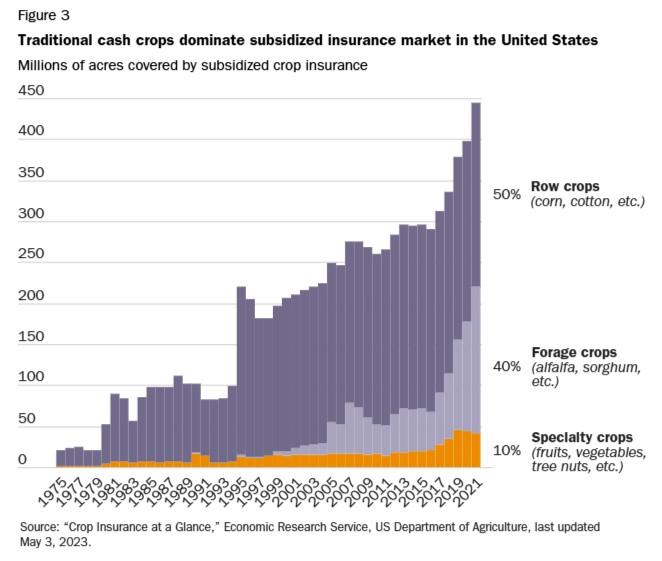

Combined with the fact that insurance for “specialty crops” (mainly fruits and vegetables) is limited and complicated, the system traps farmers into “growing the same few crops or livestock because they are the only options for which good insurance is available.” As a result, around 80 percent of all insurance premium subsidies flow to just corn, soybeans, wheat, and cotton:

And just 10 percent of all acreage covered by federally subsidized insurance goes to specialty crops:

Subsidized crop insurance also encourages farmers to keep using the same land and farming techniques and keep growing the same crops long after market conditions—losses, weather, etc.—would have told them to change things up. As Bloomberg documents, for example, “A farmer caught growing different crops between rows or terminating their cover crops too late … is at risk of having their insurance claims denied.” ProPublica adds that farmers in “some of the most flood- and drought-prone parts of the country” stay on land that is no longer productive because government payouts discourage leaving.

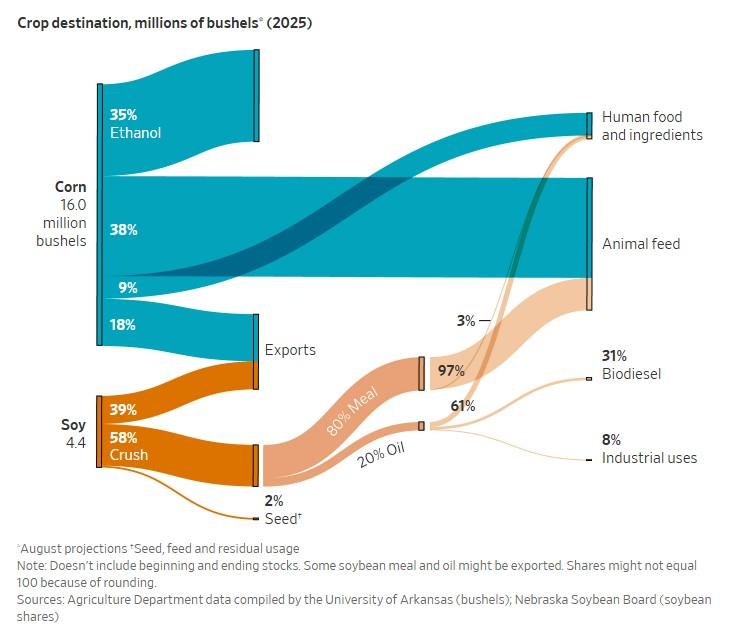

Renewable fuel policy distorts U.S. agricultural production even more. As the Journal just documented, in fact, today’s U.S. “farm economy relies heavily on government requirements for a certain amount of its crops to be blended into fuel: corn into ethanol and soybean oil into diesel.” And faced with declining export sales, American farmers now “worry that the government’s fuel mandates won’t keep pace with their expanding harvests.” Here’s the telling chart:

When, as the National Corn Growers Association’s CEO just admitted, policy has turned ethanol sales into the “lifeblood” of American corn growers, you know you have a problem.

More of the Same

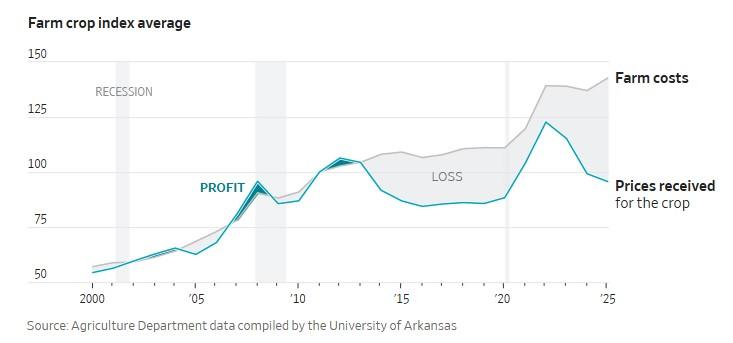

So, federal policy—subsidies, mandates, trade wars, etc.—pushes American farmers’ crop prices down, and federal policy—tariffs, immigration restrictions, etc.—pushes their production costs up. Combine those things with market factors (a big harvest, interest rates, etc.), and the result is an utterly foreseeable “crisis” of the government’s own making, with costs now far outstripping prices:

… and the much-watched fertilizer/price ratio surging to pandemic-era highs:

As U.S. farmers cut their spending, moreover, other companies in the agriculture ecosystem—including poor ol’ John Deere—are suffering too.

Unfortunately, these common problems are causing no one in Washington to reconsider U.S. trade and agricultural policy. Instead, decades of government support have farmers turning right back to the government for more of the same. One recent local news headline summarized the situation depressingly well: “Hundreds of struggling Arkansas farmers ask federal government to save them.”

Both Congress and the Trump administration, meanwhile, appear ready to oblige—beyond the billions they just spent. As my colleague Tad DeHaven and I chronicled in July, for example, the Trump administration is using federal biofuels policy to juice U.S. soybean demand and block competition from cleaner, cheaper used cooking oil from abroad. Big Corn is now lobbying Trump for an expanded ethanol mandate to achieve a similar windfall, and, the Journal reports, “Trump administration officials and lawmakers have been considering another bailout for farmers this year.” With Iowa a critical battleground for Senate control in 2026, it’s safe money that American farmers will get their wish—at taxpayers’ expense.

It would also be at the expense of the longer-term health of the broken U.S. ag economy. As DeHaven and I explained, the biofuels payoff was “the continuation of a predictable cycle: the government causes a problem that it thinks it must solve.” But instead of enacting sensible trade, immigration, and other reforms that lower farmers’ costs, open markets, and let world-beating U.S. agricultural productivity do its thing, “Politicians simply shift funds around to obscure their damaging policies, erecting a system of dependence and favoritism in the process.” And, of course, Tariff Man has no intention of stopping any time soon—even if the Supreme Court takes away one of his favorite toys.

Maybe Washington will be ready for a change when the next farm crisis arrives, but I won’t be holding my breath.

Chart(s) of the Week

Recession indicators are gaining steam

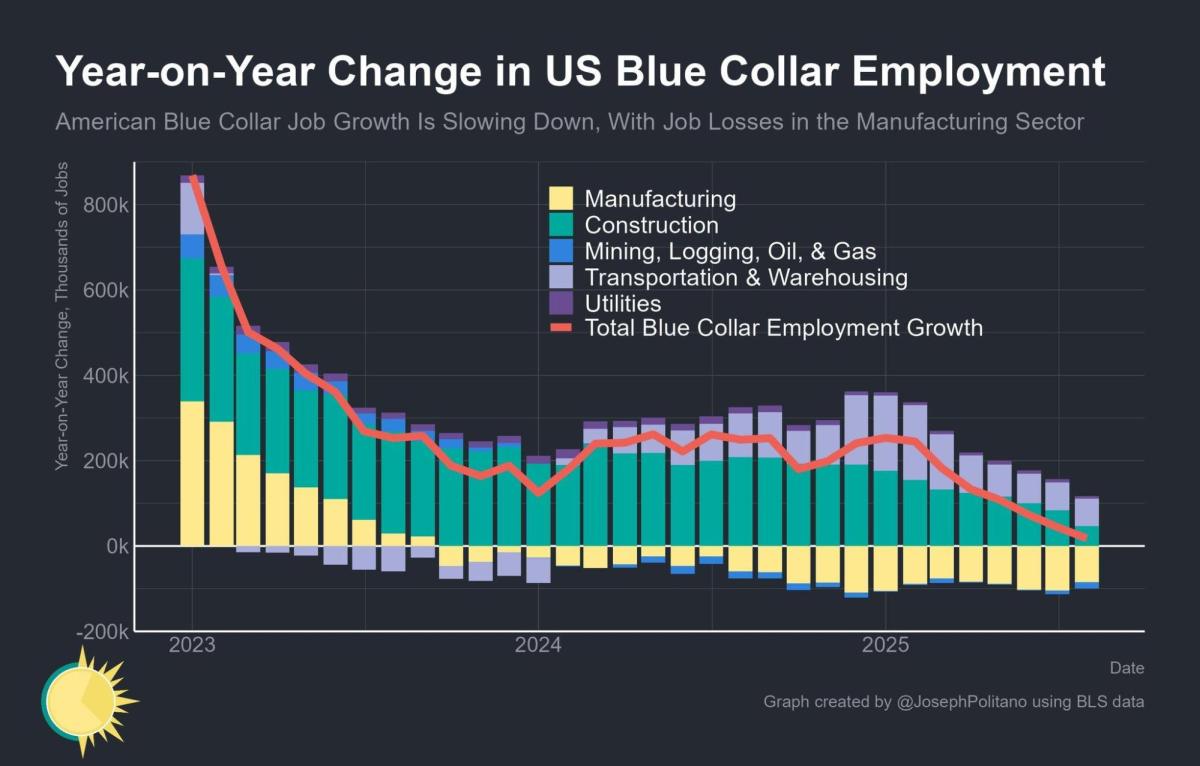

Blue collar jobs … not so great right now

The Links

I’m in The Atlantic talking about “Peronism on the Potomac”

Good primer on the economics of immigration

Actually, U.S. billionaires pay pretty high taxes

Cigarette taxes doing their thing

White House punts the economic boom to next year

Reduced immigration is now a big drag on U.S. growth

Almost all tariff revenue is from executive action

Tariffs are also a big drag on growth

India is still buying Russian oil

Automakers passing on tariffs without raising prices

This zombie U.S. Steel plant is a good example of the equity stake problem

U.S. migrant raid stirs Korean investor anxiety

Immigration enforcement causes Hispanic consumers to spend less

Tariffs raising U.S. health care prices

Tax-free tips is gonna be a gaming bonanza

Regulatory compliance is a silent tax

Costly U.S. tariff red tape (and customs enforcement)