SAN FRANCISCO — The possibilities abounded when Patrick Bailey stepped to the plate with the bases loaded in the 10th inning Friday night.

The San Francisco Giants could’ve won the game in countless ways. The smallest speck of offense, such as a sacrifice fly or a bloop single, would have been enough. Or a walk or a wild pitch would have done the job, too. They could’ve won on something stupid like a balk or a jersey-grazing fastball or an errant pickoff throw.

The Giants have 11 walk-off victories this season, more than any other major league team, and if there’s been any defining trait in this maddeningly inconsistent campaign of theirs, it’s that they accept all forms of payment in their last at-bat. This is the team that walked off the Texas Rangers in late April when a bases-empty nubber and two wild throws resulted in a Little League home run for Heliot Ramos. It’s the team that walked off the Philadelphia Phillies on July 8 when Bailey became the first major league catcher in 99 years to hit a game-ending, inside-the-park home run.

As Bailey awaited the first pitch from Los Angeles Dodgers left-hander Tanner Scott with one out, the score tied and no place to put him, his Giants teammates clung to the dugout rail in anticipation of hurdling it. A sellout crowd of 40,509 stood in the hopes of witnessing a celebratory coda. It would’ve been pure jubilation inside the jewel-box ballpark at 24 Willie Mays Plaza regardless of how mundanely the Giants coaxed 90 more feet out of pinch runner Christian Koss. The game almost ended on Scott’s first pitch to Bailey when Dodgers catcher Ben Rortvedt made a smothering stop to keep the ball from skittering to the backstop, which in hindsight, might have been an act of grace for the home team.

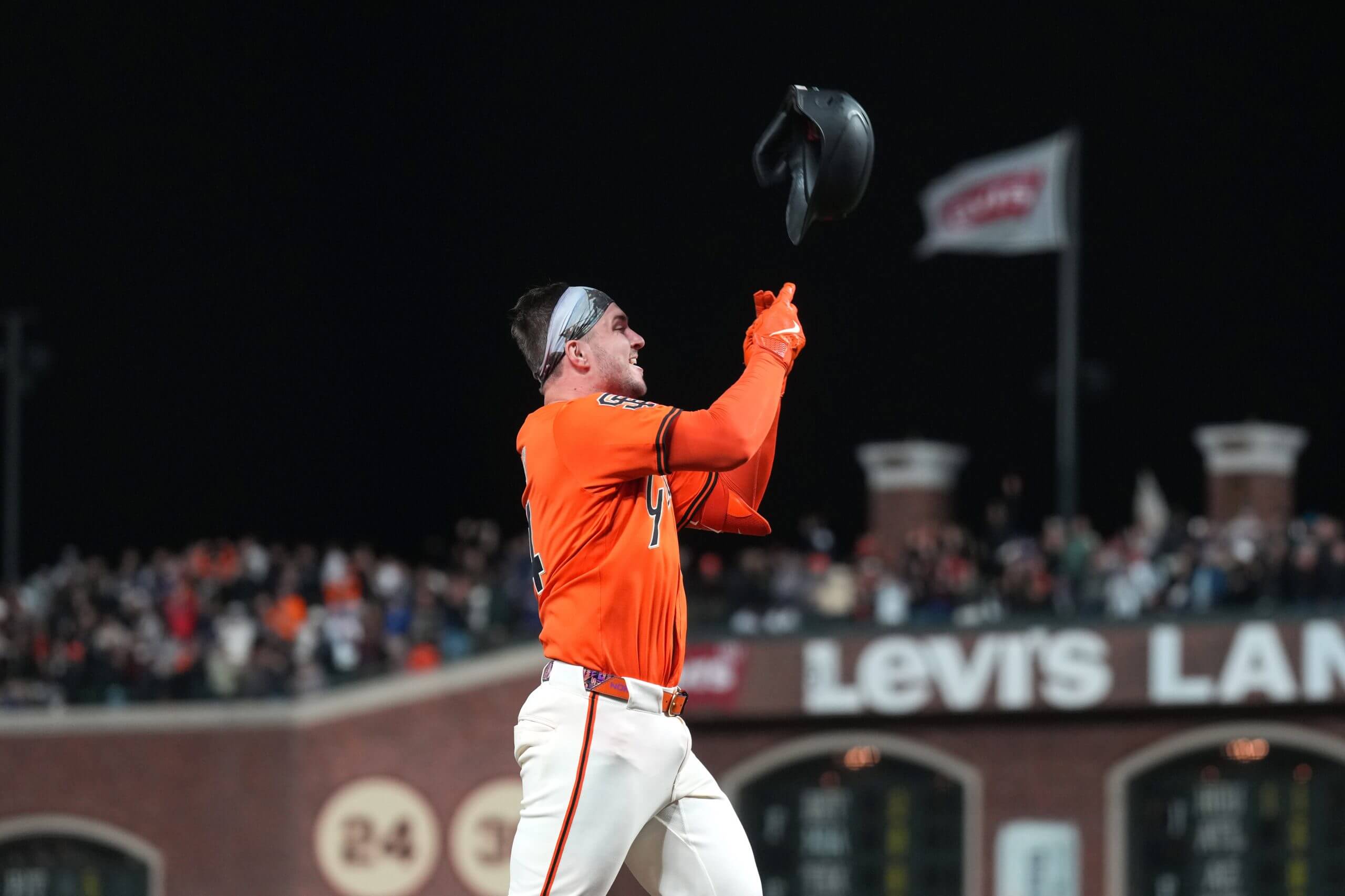

Because Scott came back with high heat. And the only speck was the baseball as it rocketed into the left field bleachers. The only stillness was within the visiting dugout. The only stupid part about Bailey’s walk-off grand slam was that it lacked all subtlety.

Bailey did more than amplify the Giants’ resurgent playoff hopes when his bases-clearing home run clinched a 5-1 victory and touched off mass euphoria in China Basin. He did more than hit the seventh walk-off grand slam in franchise history. He even did more than become the first player in major league lore to end games with an inside-the-parker and a grand slam in the same season.

It always counts for more when you do it to the Giants’ most bitter rivals. A single would’ve sufficed. When it comes against the Dodgers, though, there is no such thing as overkill.

“Both are definitely cool,” said Bailey, asked to compare his sprinting circumnavigation against the Phillies to his slam Friday night. “I’m definitely not as tired after this one.”

He’d better not get tired of hearing about it, either. Because Bailey guaranteed that a generation of breathless Giants fans will rush up to him in public places and demand a retelling. There’s a graying cohort from the Candlestick years who can still recite the details by heart — not only that Bobby Bonds hit a grand slam to beat the Dodgers on Sept. 3, 1973, but that Gary Thomasson, Doug Rader and Mike Sadek were the runners on base.

It took 52 years for a walk-off grand slam against the Dodgers in San Francisco to happen again. To set it up, it took an automatic runner (Koss pinch ran for Wilmer Flores) and a productive out (Matt Chapman’s grounder to second base) and a walk (to Jung Hoo Lee, after a semi-controversial dropped foul tip) and an intentional walk (to Casey Schmitt).

It took Justin Verlander turning back the clock on the night he marked precisely 20 years of major league service time, pitching with all the authority of a staff ace and equaling a masterful performance from the Dodgers’ Yoshinobu Yamamoto, who didn’t allow a hit from the third batter of the game through the seventh inning. It took a diving stop from Chapman at third base and a sacrificial, muscle-straining stretch from Dom Smith at first base to keep a run off the board in the fourth.

It took seldom-used pinch runner Grant McCray, moments after getting thrown out trying to score the game winner on a fly out in the ninth, jogging to right field with a cold arm and then throwing out the Dodgers’ automatic runner, Rortvedt, when he tried to advance to third base on a fly out in the top of the 10th. It took a healthy dose of the moxie and context-free fearlessness that has revived the Giants into a relevant place in the wild card standings, where they now — can this be right? — stand just a half-game behind the New York Mets for the final seat in the postseason banquet hall.

There were too many critical actors and too many storylines crammed into 10 innings Friday night. Instant classics tend to be messy that way.

“There have been extremes all year, and we’re riding this one right now,” said Giants manager Bob Melvin, who looked like a goner before the Giants ripped off 14 victories in 18 games. “It’s taken everybody to win these games. The roster looks different than it did earlier in the year and … it’s almost more fulfilling to do it the way we’re doing it right now with this group. I really can’t compare. I know this is probably as electric as the clubhouse has been after a game this year, after this game tonight.”

If Bailey was an unlikely hitting hero when his fluky drive off the brick arcade beat the Phillies, then his iconic turn Friday night bordered on ridiculousness. He has endured his worst offensive season in the big leagues. At the All-Star break, his .565 OPS was the second-worst among 226 major league hitters who compiled at least 200 at-bats. And Bailey, a switch hitter, was batting from the right side against Scott. He hadn’t hit a right-handed home run in two years and two weeks. When Bailey batted from the right side in the eighth inning against Dodgers left-hander Jack Dreyer, he swung the bat like he’d gotten lost on his way to a high school scrimmage.

“I felt terrible,” Bailey said. “I swung at a ball at my neck and chased a slider down. It might have helped in my next at-bat because I was just like, ‘Put the ball in play. See what happens.’ You’re just trying to stay short. I think if you’re trying to lift Tanner Scott, you’re probably going to pop up. You’re trying to hit a line drive and if you hit a hard line drive and they catch it, that’s part of the game. You try to set yourself up for the best chance of success.”

A Vegas card counter wouldn’t dream of having this much walk-off success. Bailey has 21 career home runs, and four have been game-enders. Put another way, 19 percent of Bailey’s home runs in the major leagues have been walk-off shots. According to ESPN’s Sarah Langs, just two other players, Tim Teufel and Billy Southworth, have ended games with an inside-the-parker and a grand slam, and neither of them did it in the same season. (If you allow double-dipping, then you might already know that Roberto Clemente accomplished both feats when he hit a walk-off grand slam in 1959.)

But the rarity or fluky quality of an accomplishment only gives it so much staying power. It needs to scratch an emotional itch, too. You can seek out Brian Johnson for testimony: Nothing makes you more of a legend among Giants fans than when you do something iconic to beat the Dodgers.

Neither Willie Mays nor Willie McCovey ever hit a walk-off home run against the Dodgers. Orlando Cepeda did it once. So did Will Clark and Buster Posey. (Here’s a wild one for you: Posey hit three walk-off home runs in his career. Bailey already has him beat with four.) A walk-off grand slam to beat the Dodgers is even rarer. Before Bobby Bonds in 1973, Leon Wagner did it on May 26, 1959, taking Art Fowler deep and, we can only imagine, sending Seals Stadium into a stupor.

Then there is arguably the most famous walk-off home run in major league history: Bobby Thomson’s pennant clincher for the Giants that beat the Dodgers in 1951. More than six decades later, in the 2014 NLCS, Travis Ishikawa delivered some sweet overkill of his own when his home run clinched the pennant over the St. Louis Cardinals.

Giants catcher Patrick Bailey rounds the bases after hitting a walk-off grand slam. (Photo: Darren Yamashita / Imagn Images)

The way Bailey is trending, who would rule out a pennant-clinching homer in his future?

“In those situations,” said Bailey, “I’m just trying to be as peaceful as I can, as relaxed as I can and not let emotions get a hold of me.”

Melvin noted that Bailey leans on the same attributes behind the plate. Even with a stint on the injured list, he ranks fourth in innings caught and already has exceeded his total from last year. He’s a runaway favorite to win his second Gold Glove Award. His outlier framing skills have made him the most valuable defender in the game in terms of Fielding Run Value. He helped to guide Verlander through seven innings and his presence is likely among the reasons the Giants’ bullpen hasn’t turned into a tire fire, even though injuries or the trade deadline took everyone from the opening-day unit except Ryan Walker and Spencer Bivens.

“His defense is off the charts,” Melvin said of Bailey. “It’s his preparation, his game calling, his understanding of the pitchers. He’s back there for nine innings. … He has a track record of being good at the plate. It just hasn’t been (consistent), and now his workload is probably as extreme as it’s ever been. To come down the stretch, with as much as he’s playing right now, and to swing the bat as well as he had all year, there’s a lot to like about Patrick Bailey.”

Verlander is coming down the stretch in a broader respect. The 42-year-old future Hall of Famer is having his most successful run as a Giant, and after so many blown leads and miscues, the team is finally proving it can function behind him. Verlander’s scoreless streak ended at 18 innings when Michael Conforto hit a home run leading off the seventh inning, but Melvin stuck with him following Rortvedt’s two-out double. The Giants issued an intentional walk to Shohei Ohtani, and Verlander threw a 95.5 mph fastball to Mookie Betts that resulted in an inning-ending fly out. Verlander’s final two pitches, numbers 104 and 105, were his hardest fastballs of the night.

“That was a special game — one of the more fun games in the regular season I’ve been a part of,” Verlander said. “Just one of those games that had a playoff atmosphere to it from the beginning. One of those games you never know who’s going to step up and make a great play or a great at-bat. This is what I told the guys after the game: In these playoffs games, the margins are really tight. You never know what’s going to help you win a game and what’s not. One run can be the biggest difference in the world. It doesn’t work that way over 162 games. It just doesn’t. But when the games really matter, the margins get tighter and those plays are exponentially big.”

Verlander called Chapman’s diving stop in the fourth “one of the best plays I’ve had a third baseman (make) behind me.” The play, which survived a replay review, resulted in Smith’s departure in the bottom of the inning. He was diagnosed with a right thigh injury and will have scans taken on Saturday. Melvin said the strain was in the upper part of the hamstring, so there’s hope that Smith, a valuable contact hitter, might avoid the injured list.

The Giants will need every part of their roster to remain in the race. They picked up ground on the field Friday night — the Mets lost and so did the Cincinnati Reds, who trail the Giants by one game — but the Giants’ half-game deficit is really 1 1/2 games because the Mets hold the tiebreaker.

McCray, the least utilized player on the roster, pinch ran in the ninth after Luis Matos reached on an error and nearly scored the game winner when he sprinted home on Flores’s shallow fly ball with the bases loaded and one out. McCray, Melvin and third base coach Matt Williams were all thinking in concert: Force Dodgers center fielder Andy Pages to make a perfect throw to extend the game. He did, and even so, the ball barely beat McCray to the plate. As McCray dusted himself off, he was already thinking about the top of the 10th.

“I got up and said, ‘Take one away,’” McCray said. “I just wanted to return the favor.”

Giants pitcher Justin Verlander reached 20 years of major league service time during Friday’s game against the Dodgers. (Photo: Darren Yamashita / Imagn Images)

McCray got his chance when Rortvedt tried to take third base on a fly ball. The throw lost no steam as it skipped twice and stayed on line to Chapman’s glove. What made the throw even more impressive is that McCray never had a chance to warm up his arm. He said he went to the indoor cage and threw a weighted ball three times in the seventh, but stopped when he knocked over the cups of water set up for Verlander to grab between innings.

McCray’s throw to third base was measured at 101.7 mph.

“Pretty hard, isn’t it?” McCray said, smiling. “Schmitty says he throws harder than me. Can you guys let him know he doesn’t?”

McCray is one of several young Giants trying to reach the postseason for the first time. Verlander, who has pitched in 24 postseason series, has been a guide for them. Fewer than 10 percent of major league players reach the 10 years of service time required to receive full pension benefits. Players celebrate the occasion with sipped bubbly and balloon bouquets. So Verlander’s teammates couldn’t wrap their minds around the two-decade milestone he reached Friday.

“Ten years is kind of the pinnacle; 20 is unheard of,” Melvin said. “All of our guys are learning, not just the younger guys but the veterans, what it takes to be that type of player and extend your career that long. And then to pitch your best baseball at this time of the year … there’s a lot of things we’re learning from JV right now. Tip of the cap. Twenty years in the big leagues, you don’t see that very often.”

Said Verlander: “My life has changed a lot. I’ve changed a lot. It’s not about the service time. It’s about that chunk of my life, where I started to where I am now, off the field particularly. It’s pretty special to have that perspective.”

Why would Verlander want to stop now? With this team, even 20-year veterans are liable to see something at a major league ballpark that they’ve never experienced before.

The Giants have 15 games to play. Suddenly, the possibilities abound.

(Photo: Darren Yamashita / Imagn Images)