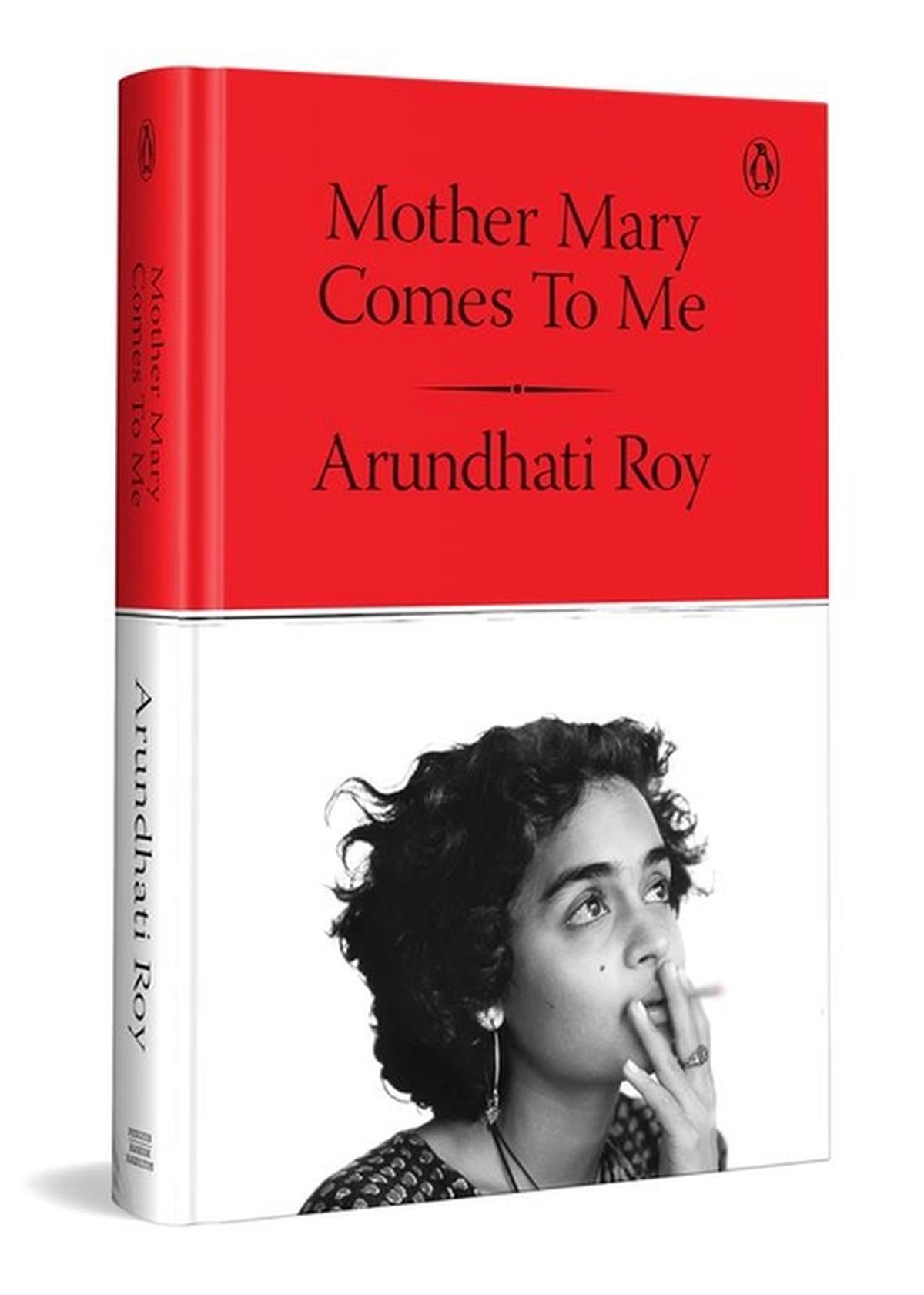

All books have covers that seek to convey or augment the content in some manner. Few do it as artfully as the Indian edition of Mother Mary Comes To Me. The book comes with half a dust jacket, with an arresting photo of the author in her youth, dreamy-eyed and dense-browed, drawing thoughtfully on a burning cigarette. Her wild curls are cut short but there’s no hiding the fact that they have a life of their own. On the back cover, her mop of curls is noticeably grey, the look in her eyes more speculative, the exquisite bone structure somewhat more rounded. When the dust jacket slips off inadvertently though, it reveals perhaps something even more significant than the passage of time between the photos: There, against the red, is a moth, evoking the formaldehyded insects mounted and framed by hobbyists and scholars back in the day.

This moth is symbolic not of her Imperial Entomologist grandfather, who died the year Roy was born and whose Ooty house homed her family when they had nowhere to go. It represents the child Arundhati’s “frightened heart… (her) constant companion”. Of all the lush imagery in Mother Mary, the pitch-perfect articulation, the impeccable use of language and punctuation – all hallmarks of Roy’s writing, so much so you can almost hear her speaking through the book – the moth is the one that flies out of the pages and settles somewhere in the reader’s own heart, evoking the terror, perhaps, of losing sight of one’s parent as a five-year-old, or of witnessing an event a seven-year-old is unable to process. It is in these all-too-identifiable themes of abandonment, of feeling, of sensing, of un-understanding that Roy makes her story universal.

Objectively speaking, of course, Mary Roy deserved her own biography the day she opened her first classroom in Kottayam. To introduce non-conventional methods of school education in a sleepy Kerala town in the 1970s was not the act of an ordinary person. To make it a success, to take parents along and produce generations of well-rounded students, is an achievement by itself. Add to that her triumph in overturning the Travancore Christian Succession Act of 1916, ensuring no other Christian woman in Kerala would be denied their share of parental property, and her immortality was assured.

‘No ordinary woman’: Mary Roy opened a non-conventional school in Kerala and fought for property rights for women.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

No ordinary mother

But because Mary Roy was no ordinary person, she begat Susanna Arundhati. And there ceased to be any question of who the biographer would be. As a result, Mother Mary — an ironical title, if there was one — is the story of two brilliant women, sharp and multi-faceted like diamonds, each creative, prickly, proud and bound together by something stronger and more elemental than an umbilical cord, something less amorphous than what they call love.

All stories of parents and children are underlined, of course, by a power imbalance. It is a while before we recognise it and, if we’re lucky, the balance evens itself out; frequently, it is the other parent who provides the counter-weight. But Mary Roy was no ordinary mother: She left her drunken husband (dismissed in the book as “the Nothing Man”) with little more than a degree in education, two small children and chronic asthma, and started out on her own at the other end of the country. She was also manipulative, abusive, cruel, hateful, often a downright monster. (Dido is particularly hard to forgive.)

“The few gruff acknowledgements that come Roy’s way — “Well done, baby girl” after she’d won the Booker — recall the spare praise millions of Gen-Xers grew up with. Roy’s tender generosity, this attempt to understand a parent without judgment, is perhaps the healing we all need in an India that thinks love is a sin, and loving bravely foolish.”

Short of silence and space, children have few defences against their parents. And so Roy fled claustrophobic Kottayam as soon as she finished high school, having discovered a love for architecture while following the legendary Laurie Baker around as he was building her mother’s school. Two years later, she stopped returning home for the holidays; the stasis continued for seven years before there was some kind of reconciliation. Not once though, during or after these seven years, according to Mother Mary, did the mother ever enquire about the daughter’s whereabouts or well-being.

Arundhati Roy and her brother Lalit Kumar Christopher Roy (LKC) at the book launch in Kochi.

| Photo Credit:

THULASI KAKKAT

When Roy wrote her exceptionally sophisticated, phenomenally successful debut novel The God of Small Things at the age of 36, she dedicated it to “Mary Roy… who loved me enough to let me go”. In Mother Mary, she admits it was “a lie. A good one. She quoted it often, as though it were God’s truth. My brother jokes that it’s the only real piece of fiction in the book”.

And yet, and yet. The tenderness that lines the pages of the book – possibly the most constant of emotions in Mother Mary – is as real as the unnameable panic symbolised by the moth. The few gruff acknowledgements that come Roy’s way — “Well done, baby girl” after she’d won the Booker — recall the spare praise millions of Gen-Xers grew up with. Roy’s tender generosity, this attempt to understand a parent without judgment, is perhaps the healing we all need in an India that thinks love is a sin, and loving bravely foolish.

Arundhati Roy won the Booker Prize in 1997 for her novel The God of Small Things.

| Photo Credit:

PTI

For ultimately, Mother Mary is as much a study of Indian society as it is an unravelling of the tangled web of a mother-daughter relationship. If her childhood marks the birth of a freethinking feminist, Roy’s later experiences in Delhi — relationships, drift, work, fame, wealth, politics, activism, aloneness — depict a womanhood that is ahead of its country. And yet, it’s undeniable that just as Mary Roy walked so that Arundhati could run, Arundhati ran so a Purulia-born Anuparna Roy could make movies and win international awards (as happened within days of the release of Mother Mary). If you need only one takeaway from this remarkable work of memory and love, it’s this: India needs to grow up for its women.

Mother Mary Comes to Me

Arundhati RoyHamish Hamilton₹899

The reviewer is a Bengaluru-based writer and editor.

Published – September 13, 2025 04:16 pm IST