On the Shelf

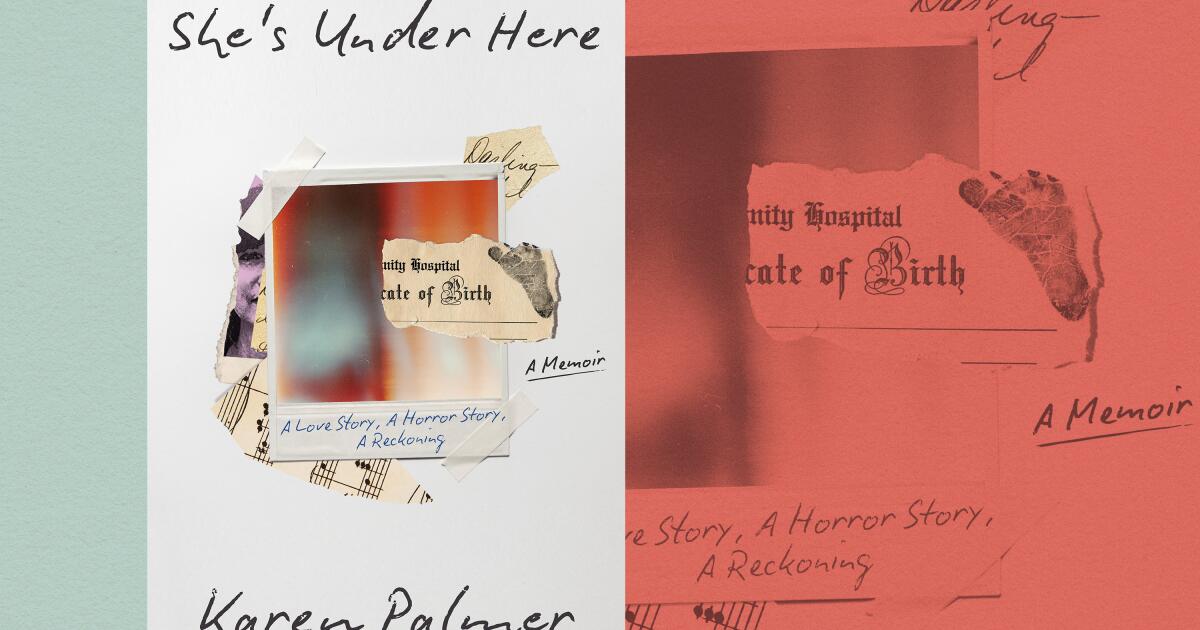

She’s Under Here

By Karen Palmer

Algonquin: 256 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Karen Palmer lives just west of the Beverly Center’s shiny consumerism, but she might as well be in a different city: Up a steep flight of stairs and behind stucco walls is her modest two-bedroom apartment. Inside, low-key furnishings and her overflowing bookshelves share space with husband Vinnie Scarelli’s fine cabinetry. But Palmer’s unglitzy Los Angeles existence has less to do with possessions than identity.

For 23 years, Palmer, Scarelli and her two daughters had fake identities, which she started thinking about the day her ex-husband Gil (not his real name) pointed a loaded gun at her pregnant belly. What happened next makes for an intense, and intensely observed, memoir that has taken Palmer nearly 50 years to untangle. “She’s Under Here” details forgery, a child’s kidnapping, a mental breakdown, struggles to stay afloat — and joy.

Karen Palmer — the name she chose and still uses — was born in L.A., but she doesn’t know where or precisely to whom. As an adult she learned her biological mother’s name. Nothing more. Adopted in infancy, Palmer was raised in Silver Lake, her upbringing impacted by her journalist father’s alcoholism and her stay-at-home mother’s religiosity. She got pregnant at 15 and her parents sent her to a nearby Catholic home for unwed mothers where she gave birth to a baby boy, whom she placed for adoption. Despite deep grief over these events, Palmer attended UCLA to study piano performance. But she left without earning her degree after meeting and marrying Gil.

Palmer was still in high school when she started working as a part-time secretary at an office supply company. Gil, her charismatic, not-yet-divorced boss, was not just the manager but the ringleader of a group of friends who referred to him as “Mr. Fun.” He relished the attention. Before long, Gil convinced her to drive to Las Vegas for a weekend getaway. She was entranced by a man who could win and lose big at blackjack without missing the chance to order another round of J&B on the rocks for himself and Harvey Wallbangers for her: “You’ll like it, baby. It’s sweet.”

Fast-forward 14 years — past the couple’s wedding (Palmer was 19), the births of two daughters, many instances of domestic violence and Palmer falling in love with Gil’s friend Scarelli — Palmer asked for a divorce and received it. But Gil, already furious that Palmer and Scarelli were a couple, descended further into alcoholism. He took a trip with their 7-year-old soon after. Palmer met them at the airport upon their return and handed the baby to Gil while she embraced the older child. When Palmer looked up again, Gil and the younger child had disappeared into the terminal crowd.

Palmer, speaking from her L.A. home, pauses for a long time when asked if she knew she had made a mistake. “It was such a harried moment,” she finally says. “At first I thought, ‘Oh here comes my family,’ and then I could feel the hatred coming off him the nearer he came. It was confusion and fear. The more afraid I was of him, the more groveling I became.”

“Over the course of marrying and building a life and the hair-raising things we went through, Vinnie and I essentially endured a kind of war together,” says Karen Palmer.

(Vincent Scarelli)

Palmer’s baby girl was gone for nine long days during which she enlisted help from the authorities, only to realize the law upheld a father’s right to see his children. When Gil finally returned the baby, making sure Palmer saw that he had a gun, Palmer said to Scarelli: “We have to run.”

Many factors complicated the family’s decision to run, including the children, Palmer’s aging mother and their financial instability. Although Palmer and Scarelli wound up in other states for years, their story demonstrates how many identities are lost, found and disguised in L.A. Loading a car with the minimum (“one pot, one pan, two car seats”), Palmer and her family drove to Boulder, Colo. They bartered his house-painting skills for a temporary apartment and set about obtaining documents that would allow them to work and register their daughters for school. Palmer applied her graphic design skills to forging birth certificates with new names. Yes, she says, they committed fraud, but not identity theft. With those documents and a family friend’s California address, they essentially invented new versions of themselves.

“Over the course of marrying and building a life and the hair-raising things we went through, Vinnie and I essentially endured a kind of war together,” says Palmer. “Our lives were in danger and we needed to protect young children.” She and their daughters joke about “Saint Vinnie,” but she adds, “I feel completely able to give and receive love in spite of trauma, and I think that’s because one person sacrificed everything in his life for me and has never for one second expressed regret.”

A year or so after she learned of Gil’s 2008 death, Palmer felt safe enough to head to a Social Security office and “straighten everything out.” She writes about how she came to see that Gil’s oft-repeated adage “you are who you say you are” should actually be “you are what you do.”

The coroner’s investigator, who had retraced Gil’s life before his demise, helped. “He said, ‘You did the right thing’ in protecting your children, explaining that when a substance abuser falls off the deep end, the endgame is sad and ugly. Having a stranger tell me that held weight.” Palmer says since her family’s flight, not enough has changed to protect women from domestic violence. “Women still are not believed. One of the troubles that I had with writing this is that I wasn’t beaten. I was always worried that what happened to me wasn’t ‘bad enough.’ But writing this memoir shows me that yes, it was bad enough. Particularly because it involved a man with a gun.”

Twenty years after leaving L.A., Karen Palmer returned in 2005 and has lived in the city with Scarelli ever since. Now that the couple has straightened out their identity issues, their bond is stronger than ever — and so are their relationships with Palmer’s two adult daughters. “L.A. is where people reinvent themselves, but I had been gone so long that the city itself changed. It’s like when a street looks different, but you can’t remember what was there before. The city has subtly shifted. It’s not the same and yet it is the same,” she says. As she sits at her piano, sunshine filtered through laurel trees, Karen Palmer is now at home — in her city and with herself.