From presidential candidates to electric cowboys — these were the roles that showcased the late, great actor at his finest

An up-and-coming young actor in the 1960s, a sex symbol in the 1970s, a movie star (and Oscar-winning director) in the 1980s, an elder statesman in the 1990s and an éminence grise in the 21st century — Robert Redford’s screen career spanned six decades and gave us too many memorable performances to count. Which, naturally, has not stopped us from singling out 20 roles that we believe highlight the late, great actor’s immense talents. From presidential candidates to professional thieves, legendary journalists to legal eagles, electric cowboys to horse whisperers, here are our picks for Redford’s best.

‘The Chase’ (1966)

Image Credit: Everett Collection

Redford had a few movies — not to mention numerous bit parts on TV shows, a handful of stage performances, and a Golden Globe for a small role as an alcoholic, bisexual actor in 1965’s Inside Daisy Clover — under his belt when he joined Arthur Penn’s Southern-fried melodrama. Yet this is arguably the first time that audiences got a proper glimpse of what the future above-the-title star was capable of. Cast alongside Marlon Brando, Jane Fonda, and fellow future screen icon Robert Duvall, Redford is Bubber Reeves (!), an escaped convict sneaking home to see his wife. His anticipated return riles the townsfolk into a mob-mentality fervor, and no, it doesn’t end well for good ol’ boy Bubber. Redford spends a lot of the movie literally on the run. But his way of holding your attention doing the quieter moments is evident, as is his chemistry with Fonda. And though Redford often bemoaned his early work, he holds his own against Brando in their few scenes together. Combined with his performance in the equally torrid This Property Is Condemned a few months later, this was the beginning of his ascent toward stardom. —David Fear

‘Barefoot in the Park’ (1968)

Image Credit: Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

Redford had already played the part of newlywed Paul Bratter in the original 1965 Broadway production of Neil Simon’s hit, opposite Elizabeth Ashley; the play gave him his first real taste of success. So it was a no-brainer that he’d be cast in the screen adaptation, with his Chase co-star Jane Fonda subbing in as his free-spirited wife. The two will have their ups and down as a young couple, with the uptight Paul eventually learning to lighten up and follow his spouse’s live-in-the-moment lead (see title). And movie audiences got to see exactly why Redford was singled out as a highlight of the show’s theatrical run. The rapport — and, frankly, heat — between the two helps sell the conservative-versus-kooky dynamic, and Redford displays a casual sense of comic timing that he’d put to great use down the road. His sex-symbol era had now commenced. —D.F.

‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’ (1969)

Image Credit: © 20th Century Fox/Everett Collection

Legend has it that William Goldman’s script was purchased by 20th Century Fox on the basis that Butch Cassidy would be played by Paul Newman — the star of Hud, The Hustler, and Cool Hand Luke was already a name that guaranteed asses in seats. Yet no one could figure out who to cast as Sundance. Jack Lemmon said no. So did Steve McQueen. It was Newman’s wife, Joanne Woodward, who suggested Redford, who she’d seen on Broadway. And thus one of the screen’s great bromances was born. Watching Newman and Redford pal around as two members of the Hole in the Wall Gang and go on the lam together, it seems inconceivable that anybody else could have played these parts. With all due respect to Katherine Ross, the movie is a love story between these two outlaws, and that’s thanks to Redford complimenting Newman’s flinty rebelliousness with his own maverick streak. They were a match made in heaven, destined to jump off that cliff and face down the entire Bolivian army together. The two remained lifelong friends, and though Redford would be paired with several generations’ worth of actors over his career, he never had a better co-star. —D.F.

‘Downhill Racer’ (1969)

Image Credit: Everett Collection

After he became a superstar cowboy as the Sundance Kid, Redford went for offbeat sports roles as an obsessive skier in Downhill Racer and a dirt-biker in Little Fauss and Big Halsy. He hits the slopes in Downhill Racer, battling U.S. Olympic ski team coach Gene Hackman. It was a passion project for Redford, as a lifelong fanatic who’d already built his own Sundance resort. “For me, personally, skiing holds everything,” Redford said at the time. The movie, which also marked his first time producing, filmed in Switzerland. “Politics surround this sport, like any business,” he said. “People are cruel to each other. And the sport is cruel, too, although usually you think only of the beauty of it.” —Rob Sheffield

‘The Candidate’ (1972)

Image Credit: Everett Collection

The Candidate is the ultimate showcase for Redford as the JFK figure of the 1970s: young, idealistic, handsome, full of noble dreams. In Michael Ritchie’s political satire, Redford plays Bill McKay, the innocent liberal preppie drafted into his first political campaign, going up against a powerful Republican senator from California. Redford learns the game, with Peter Boyle as the cynical operator behind him, only to get corrupted by the political process. Released during the 1972 presidential election, The Candidate accidentally became a perfect portrait of the nation in the era of Watergate. It thrives on Redford’s unique combination of natural golden-boy charisma, earnest moral grit, and sly comic chops. —R.S.

‘The Hot Rock’ (1972)

Image Credit: © 20th Century Fox/Everett Collection

On The Brady Bunch, Alice once said she wanted to be cremated and have her ashes thrown on Robert Redford. The Hot Rock is why. He’s at his most fetching here as a wily jewel thief, the picture of devil-may-care charm at its blondest. The Hot Rock is a comic New York City heist caper, Peter Yates’ film of a Donald Westlake crime novel, made on location in the early 1970s, right before the “Ford to City: Drop Dead” era. Redford sets out to steal a priceless gem from the Brooklyn Museum, on a team with George Segal, Zero Mostel, Moses Gunn, and other Seventies legends. Sleater-Kinney claimed this movie for the riot-grrrl generation with the cover of their 1999 punk classic The Hot Rock. —R.S.

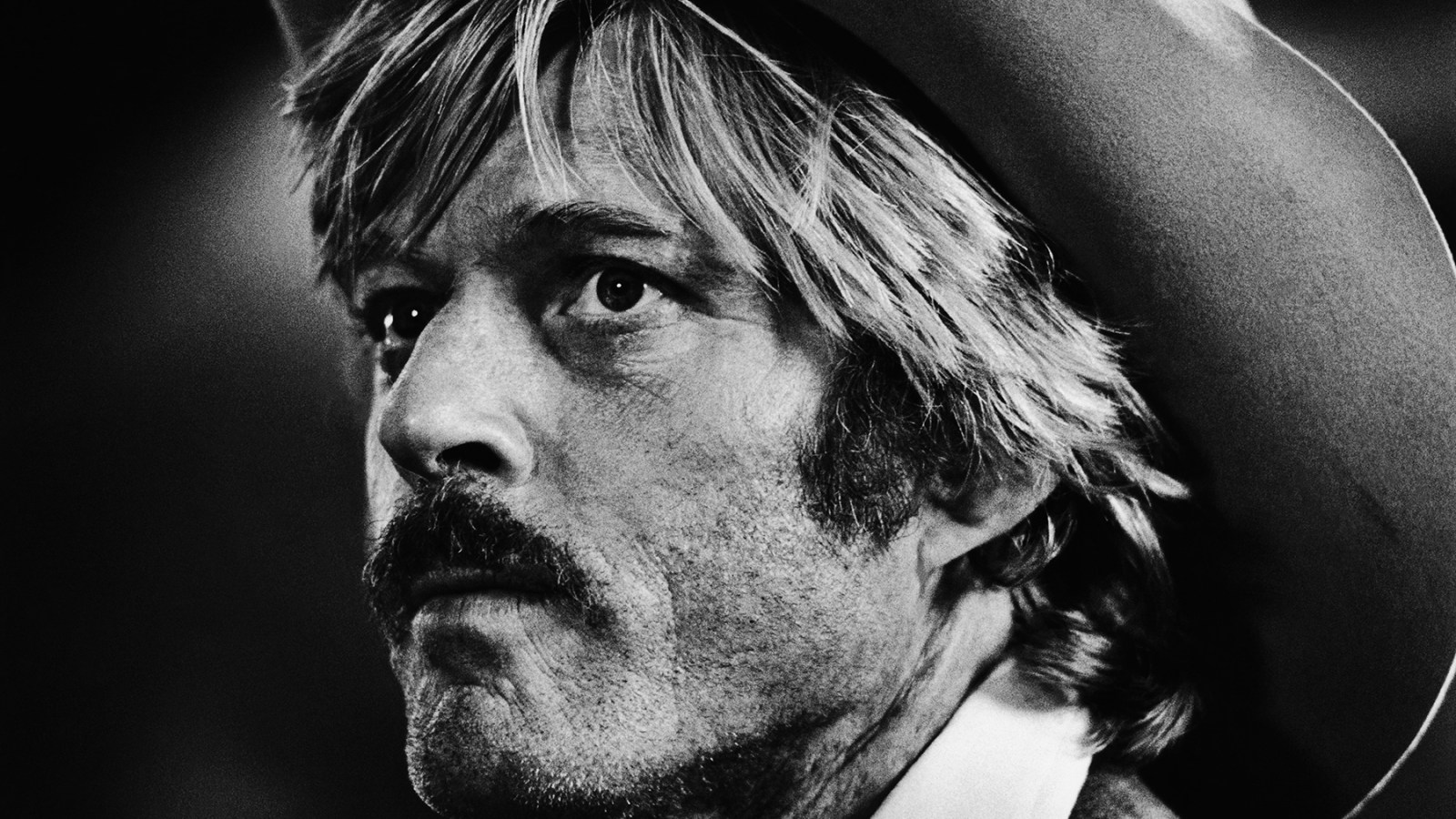

‘Jeremiah Johnson’ (1972)

Image Credit: Everett Collection

This mountain-man epic was originally set up as a Clint Eastwood vehicle; when he dropped out, Warners turned to Redford, who enlisted This Property Is Condemned director Sydney Pollack to call the shots. It’s peak granola Redford, a thinking-man’s Western that appealed to the star’s inner nature-lover and outer rugged-matinee-idol appeal. (This is ground zero of the Seventies-style bearded sex symbol, and everyone from Jason Momoa to Bon Iver should be forced to pay royalties in perpetuity.) A veteran soldier disillusioned by society’s warring ways, Jeremiah takes to the Rocky Mountains with the intention of living as a trapper. He’ll encounter friends and enemies along the way, all while learning to live off the land. Had its legacy simply been showcasing Redford’s ability as an outdoorsman capable of giving a sublime performance — consider this a literal dry run for his near-dialogueless seafaring adventure All Is Lost — Jeremiah Johnson would still be a prime example of why he was such a great star for his socially conscious era. The fact that it also gave birth to the world’s greatest meme only makes us love it more. —D.F.

‘The Sting’ (1973)

Image Credit: Sunset Boulevard/Corbis/Getty Images

Caper movies are a sort of con game, an effort to keep viewers engaged through every twist and turn for the cost of a movie ticket. And there was no better con man of his era than Robert Redford’s Johnny Hooker. Reuniting with the co-star (Paul Newman) and director (George Roy Hill) of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Redford brought the confidence for a film that would shape his legacy as much as any in his body of work. By this time, Redford’s magnetic onscreen presence was a known quantity, allowing him to wield that star power like a weapon. It’s the tousled blonde hair peeking out from under his ascot cap, that blinding smile, his rakish good looks, and an infectious laugh. How could anyone say no? Instead of hiding his beauty, Hill directs Redford to lean into what people already loved about him, a blinding charm that’s only amplified through his chemistry with Newman. A piece of pure, unabashed entertainment, The Sting would not only win Best Picture, but land Redford what would somehow be his only Oscar nomination for acting. What a con. —Brian Tallerico

‘The Way We Were’ (1973)

Image Credit: Everett Collection

Memories, light the corners of our minds. The Way We Were has the iconic Seventies pairing of Robert Redford and Barbra Streisand, in the wildly popular drama of two star-crossed lovers. They meet in college in the 1930s — she’s a Marxist Jewish intellectual activist, he’s a blonde WASP novelist. Their stormy romance rages through World War II to McCarthyism to the Hollywood blacklist. The StreisFord opposites-attract chemistry is off the charts — the Brooklyn noodge vs. the Santa Monica tennis jock — establishing them both as the key romantic leads of their era. Every mom in America saw it four times. (As Pauline Kael wrote, “It’s good to see Redford with a woman again after all that flirting with Paul Newman.”) It became one of 1973’s box-office sensations, with Barb’s hit theme song to evoke misty watercolor memories of the way we were. —R.S.

‘The Great Gatsby’ (1974)

Image Credit: Everett Collection

It wasn’t the first movie adaptation of The Great Gatsby — and it may or may not be the best, depending on your Baz Lurhmann tolerance level. But it was a Seventies blockbuster, turning the classic 1925 F. Scott Fitzgerald novel into an over-the-top Hollywood fantasy of the Jazz Age, directed by Jack Clayton with a Francis Ford Coppola screenplay. Redford’s Jay Gatsby is the tormented bon vivant of West Egg, with his Roaring Twenties idea of style — nobody has ever said “old sport” with less irony than Redford. He carries a torch for Mia Farrow’s Daisy, with Bruce Dern as her jerk husband Tom. But he captures the steely self-discipline behind the obsessive social climber; Redford convinces you that he’s the dashing romantic Gatsby dreamed of being all along. —R.S.

‘Three Days of the Condor’ (1975)

Image Credit: Everett Collection

Few movies captured the woozy paranoia of the mid-1970s better than Sydney Pollack’s thriller, in which Redford’s C.I.A. analyst (code name: Condor) takes a lunch break and returns to his office in New York’s Upper East Side to find his co-workers murdered. It turns out to be an inside job, and the intelligence agency employee must go on the run before assassins track him down in the name of tying up loose ends. Redford gets a workout, running all over Manhattan, outwitting his betrayers and wooing Faye Dunaway all in the span of a few afternoons. He’s a thinking-man’s action hero, and not even the post-Watergate bad vibes can keep him from losing his cool. —D.F.

‘All the President’s Men’ (1976)

Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Bob Woodward would probably concede that it was quite generous to cast the most handsome man alive to play him in a movie. On paper, Redford wasn’t a great fit for the role so much as the sugar to make the medicine go down: If you’re going to ask audiences to spend two hours with a couple of rumpled, workaholic journalists sniffing out leads, it helps if one of them looks like the Sundance Kid. But it was Redford himself who spearheaded Alan J. Pakula’s rigorously fact-based newspaper procedural, purchasing the rights to Woodward and Bernstein’s book about how they methodically uncovered the Watergate coverup. And that genuine interest in the material colors his vanity-free performance, which forgoes movie-star grandstanding at every turn in favor of unfussy, focused professionalism. No self-flattery was ultimately necessary for writers to see themselves in his take on the Washington Post veteran, because Redford fully commits to the unglamorous nature of investigative reporting, looking right at home with a phone balanced on one shoulder and a stack of documents under his nose. He truly disappears into the work — hardly a small thing for a Hollywood legend of his wattage. —A.A. Dowd

‘The Electric Horseman’ (1979)

Image Credit: Sunset Boulevard/Corbis/Getty Images

Redford gave one of his most roguishly charming performances as Sonny Steele, a washed-up, drunken rodeo star who steals a million-dollar horse from an abusive conglomerate, rides it down the Las Vegas strip, and aims to turn it loose. Directed by Sydney Pollack, it’s a cops-and-cowboys lark of the highest order, but Redford made it a genuine, heartfelt appreciation of the American West, both its geography and its culture. When Jane Fonda’s city-slicker reporter Hallie Martin catches up with Steele out in the desert, she slowly melts thanks to the rough-hewn wrangler’s knowledge of the land. “This country’s where I live,” Steele says matter-of-factly. Naturally, they fall in love, but Steele, ever the drifter, doesn’t hang around long. Just like the horse, he needs to be free. —Joseph Hudak

‘The Natural’ (1984)

Image Credit: Everett Collection

Right, Hollywood changed the ending to Bernard Malamud’s somber novel, which saw its cautionary-tale hero Roy Dobbs not win the big game or walk off into the sunset. But Barry Levinson’s adaptation of The Natural understood that it would be irresistibly mythic to have Robert Redford come to the plate, his side bleeding, and hit the walk-off home run that clinches the pennant for the New York Knights, Randy Newman’s stirring score serenading him as he runs the bases in slow-motion. It’s a glorious moment in the Oscar-nominated film, which found the golden-boy star comfortably shifting into middle age onscreen, his Dobbs an aging athlete filled with regret but determined to make things right both on and off the diamond. If in his daring 1970s films, like Three Days of the Condor and All the President’s Men Redford utilized his stardom to create provocative dramas that spoke to the dark side of America’s political climate, here he was offering a bittersweet fantasy of redemption and hope restored. He was rarely more moving, or more beautiful. —Tim Grierson

‘Out of Africa’ (1985)

Image Credit: © MCA/Universal Pictures/Everett Collection

A decade after director Sydney Pollack made a screen couple out of Redford and Streisand, he did the same thing for Redford and Meryl Streep. Out of Africa was based on the autobiographical novel by Isak Dinesen, about World War I-era European aristocrats in Kenya. Streep plays a Danish plantation owner (cough) who finds romance with Redford as a British big-game hunter (double cough), with a tiny support role for the already mega-famous Iman. Even at the time, the colonialist milieu was hard to take, but Out of Africa won an Oscar for Best Picture and another for Pollack as Best Director. —R.S.

‘Legal Eagles’ (1986)

Image Credit: © MCA/Universal Pictures/Everett Collection

Does it get any more Eighties than this? Legal Eagles is a rom-com about sexy Manhattan lawyers… wait, come back!…with a sensual theme song from Rod Stewart, the erotically charged “Love Touch”! Redford plays an assistant D.A. who gets caught up in the case of a performance artist (Daryl Hannah) accused of stealing a painting from a crooked millionaire. He teams up with a lawyer played by Debra Winger, and before you know it, there’s mystery, murder, Terence Stamp as a sleazy art dealer, and because this film was made in the 1980s, Brian Dennehy. But Redford’s charm holds it all together. It was director Ivan Reitman’s follow-up to Ghostbusters — as he told the L.A. Times, “It was easier getting Redford than it was getting Bill Murray.” —R.S.

‘Indecent Proposal’ (1993)

Image Credit: © Paramount Pictures/Everett Collection

Sometimes, a preposterous high-concept movie idea will work if you cast the right actor. Fatal Attraction director Adrian Lyne did just that when he tapped Redford to play John Gage, a mysterious billionaire who offers down-on-his-luck David Murphy (Woody Harrelson) a million dollars to spend one evening with his wife Diana (Demi Moore). A box-office smash that invited plenty of controversy — was the film sexist? Was it secretly feminist? — Indecent Proposal could have felt like a stale leftover from Hollywood’s portraits of Reagan’s America with its sleek, ambiguous look at love, money, and morality. But Redford lent the potentially tawdry plot line a melancholy gravitas as his Gatsby-esque figure laments his life, which has afforded him untold riches but little in the way of meaningful human connection. When Gage wistfully recalls a young woman he briefly glimpsed long ago who has forever enraptured him, Redford transcended the speech’s clear parallels to a similar speech in Citizen Kane, in the process revealing a broken man that no amount of money can fix. —T.G.

‘The Horse Whisperer’ (1998)

Image Credit: © Walt Disney Pictures/Everett Collection

For a certain millennial cohort, The Horse Whisperer might have been their first exposure to Redford the director. While many movie snobs at the time dismissed the film as overly glossy, sappily sentimental Oscar bait, others (ahem) saw a gorgeously filmed, sensitively rendered picture of grief and trauma’s myriad complexities. (The words “grief” and “trauma” weren’t quite so overused in those days.) Yes, it is all rather stately and traditional and luxe, but The Horse Whisperer is also gently insightful about human interaction — between mother and daughter, husband and wife, uptight city girl and philosopher-cowboy country boy. It’s a hushed, aching romance and a thoughtful portrait of a child healing from what could otherwise become a life-defining calamity. The Horse Whisperer is a lovely and goodhearted film, as reverent of emotional experience as it is of Redford’s cherished mountain vistas. —Richard Lawson

‘All Is Lost’ (2013)

Image Credit: © LionsGate/Everett Collection

By the 2010s, Redford had mostly stopped acting outside of his own movies. But he got back in front of the camera for Margin Call writer-director J.C. Chandor’s ambitious follow-up, which focused on an unnamed man in the middle of the Indian Ocean whose small vessel has just hit a shipping container, causing significant damage to his craft. Playing the film’s only character, and speaking only a few dozen words over the course of the story, Redford delivered his most purely physical performance, giving us a solitary soul who fights to stay afloat as we try to piece together clues regarding who he is. Well into his seventies by that point, Redford remained a striking presence, his boyhood athleticism still on display as the character’s battle with nature becomes a metaphor for humans’ endless wrestling with mortality. All Is Lost’s primal thrill was heightened by the beloved star at its center, who never stopped taking chances on the way to one of his greatest late-career roles. —T.G.

‘The Old Man and the Gun’ (2018)

Image Credit: Fox Searchlight Pictures/Everett Collection

No posthumous highlight reel could hope to encapsulate the iconic stature of Robert Redford better than his final star vehicle. Though technically not the actor’s swan song (his last credits are a couple of voice-only gigs and a Marvel cameo), David Lowery’s elegiac outlaw yarn arranged a perfect parting showcase for his twinkling charm. His character, a laid-back outlaw still politely robbing banks well into his twilight years, is based on a real person. But he could just as well be an older version of any classic Redford desperado, from Sundance to Johnny Hooker to Jeremiah Johnson — a notion Lowery underscores by splicing in footage of the actor from his youth. The bittersweet magic of the movie is how it makes Redford’s relaxed gravitas (and his chemistry with fellow screen legend Sissy Spacek) the whole show, while giving him the opportunity to wave farewell on his own mythic terms. You soak in his star power, undiminished by age or its ultimate ephemerality. —A.A.D.