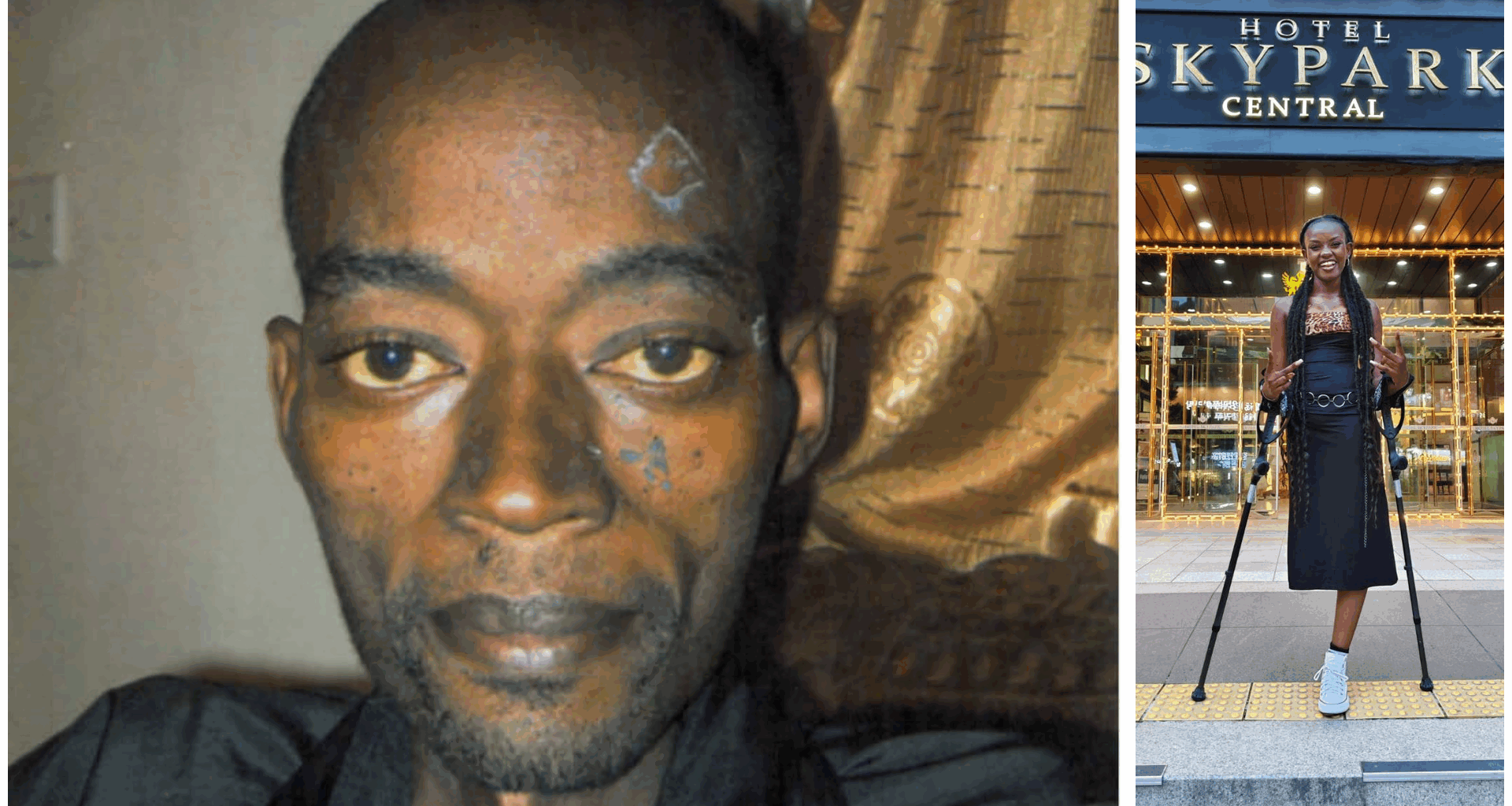

The late Elly Abong’o and his daughter Fridah Lakita / HANDOUTIn May 2010, Elly Abong’o, a well-known media personality in the sports world, succumbed to colon cancer. The former Citizen TV sports news anchor who also worked for British Broadcasting Corporation’s Swahili (BBC’s) and Radio Simba then, left behind a three-year old girl who had innocently and helplessly watched her father fight the ailment.

The late Elly Abong’o and his daughter Fridah Lakita / HANDOUTIn May 2010, Elly Abong’o, a well-known media personality in the sports world, succumbed to colon cancer. The former Citizen TV sports news anchor who also worked for British Broadcasting Corporation’s Swahili (BBC’s) and Radio Simba then, left behind a three-year old girl who had innocently and helplessly watched her father fight the ailment.

As the disease developed, she noticed that she could no longer take the long walks with her father. Play time became limited as Elly tried to bravely combat the disease, confident that he would emerge triumphant. Sadly, he died, leaving his young family behind. Unfortunately, he also left a gene in his offspring that put his daughter Fridah Lakita at risk of developing cancer.

Seven years after his death, Lakita was diagnosed with a bone cancer known as osteosarcoma, which resulted in the loss of her right leg.

Her mother, Joyce Abong’o, says the girl began experiencing pain on her knee in 2017.

“I would massage her to ease the pain but on one night in September 2017, the pain became intense,” she says.

“We sought medical attention and a scan revealed she had a tumour.”

Although her first round of treatment was successful, the cancer relapsed and she is currently undergoing treatment in India, where she got amputated in 2018.

Doctors believe the condition was as a result of Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), a genetic disorder that runs in her family.

“Elly was orphaned at a tender age and his mother, brother and sister, who have all died, are suspected to have all died of cancer-related disorders,” Joyce says.

Therefore, Elly, and later his daughter, were vulnerable to LFS and associated cancers.

ABOUT THE DISORDER

Li-Fraumeni syndrome is a rare genetic condition first described in 1969 by Dr Joseph Fraumeni and Dr Frederick Li in 1969 as caused by mutations in the TP53 gene, commonly known as the “guardian of the genome”.

It dramatically raises the risk of cancers such as sarcomas, breast cancer, brain tumors and leukemia, frequently affecting children and young adults.

Because of its hereditary nature, entire families can be impacted across generations, making community support essential.

Researchers reveal that everyone with this condition has a 90 per cent chance of developing a type of cancer before they reach the age of 60.

According to the LFS Association, “Cancers related to this condition may occur at any age, but a characteristic feature of LFS is a high risk for cancer occurring in childhood.”

Many of the females who have LFS are at a high risk of developing breast cancer.

Still, Lakita’s experience shows that people with LFS can develop other types of cancer, which calls for regular screening.

After chemotherapy, Lakita developed Myelodysplastic Syndromes, a condition that occurs when the cells that form blood in the bone develop abnormalities and the marrow cannot make sufficient healthy new blood cells.

According to the American Cancer Society, “Many of the blood cells formed by these bone marrow cells are defective. As these defective cells build up in the bone marrow, they can crowd out normal blood cells.”

Therefore, it is important for cancer patients to undergo regular screening to determine whether they are at risk of developing other cancers due to LFS.

During screening, healthcare providers use genetic testing to diagnose the syndrome. They first examine your medical history as well as that of your family. If LFS is suspected, they consider whether your parents or siblings have been diagnosed with cancer before the age of 45.

They also consider whether your grandparents, uncles, nieces, nephews and even grandchildren have been diagnosed with any type of cancer before they are 45 years old. Screening and early diagnosis allows doctors to treat any potential cancers, improving the chances of survival.

Although LFS cannot be treated, it can be managed, with cancer treatments provided the same way that people without the condition receive it.

Treatment may involve standard therapies, such as chemotherapy and radiation. In some cases, such as Lakita’s, treatment may involve surgery.

However, people with Li-Fraumeni syndrome are at higher risks of developing cancers after undergoing radiation exposure. Therefore, doctors adjust treatment to minimise radiation therapy.

Once diagnosed with LFS, it is important to undergo regular screening for early detection of cancers that may be triggered by the condition.

SERIAL CANCERS

Research shows that people with the syndrome may develop more than one cancer.

One cancer survivor, Judy Melody* (not her real name), says she developed adrenal cancer as an infant.

At 24 years of age, she was diagnosed with stage II breast cancer.

“I had a lot of scans, tests, lost my hair and ultimately had a double mastectomy,” she says.

“Losing my hair was hard for me at first, but I quickly realised that it’s only hair and that hair grows back.”

Later still, she was diagnosed with thyroid cancer, melanoma and sarcoma. It was only after the diagnosis of melanoma that doctors suspected and confirmed the existence of Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

Melody understands that cancer will be a permanent part of her life. Yet, her story is evidence that no one should lose hope due to a cancer diagnosis.

“Learning I had Li-Fraumeni actually put me at ease. I finally understood why I kept getting cancer,” she says.

“With this genetic information, my doctors know to monitor me very closely, which I am thankful for. Even though I know I’ll face cancer throughout my life, I won’t let cancer and Li-Fraumeni syndrome define who I am. Instead, they empower me.”

The syndrome and the development of cancer leave a gaping hole in the family’s pockets and becomes a barrier to seeking financial prospects.

Joyce worked as a film journalist in the mainstream media, and she had to resign to give all her attention to her late husband after he was diagnosed with colon cancer then.

Her daughter’s condition has further drained the family’s financial resources. Surgery and treatment for Lakita was very expensive during the first round. Since then, they have been travelling to India every year for checkups, and Lakita had her prosthesis surgically fixed.

Joyce has to pay heavy fees for travelling and medical expenses since the checkups and reviews have to be done annually.

Since Lakita is physically developing like other girls her age, her prosthetic leg has to be checked and adjusted to suit her stage of physical development.

Lakita is not the only LFS patient Kenya. Lack of awareness and the unavailability of the LFS TP53 gene testing for diagnosis in the country are challenges that accost many Kenyans with LFS symptoms.

For example, Lakita and her mother have to settle in India (during treatment period) since they cannot travel as frequently as required for check-ups, treatment and management of the condition.

Myths about LFS also pose significant challenges to patients. “Many Africans believe LFS is a form of curse of some sort and they likely are not educated or there has not been consistent awareness to educated people about LFS,” Joyce says.

“There is a lot of stigmatisation for many patients if they happen to experience LFS disorders or cancer within the family set-up, thereby causing a lot of trauma to the families.”

FINDING SOLIDARITY

As LFS is a rare condition, it is not easy to find people with similar experiences with whom to share the challenges and pains of the journey.

Fortunately, there have been dedicated efforts to bring people with LFS from all over the world together.

The Li-Fraumeni Syndrome Association (LFSA) US Chapter holds international events that bring together people with the condition from all over the world.

The association’s president, Jean Perry, says LFSA was born out of the realisation that young people living with LFS needed a dedicated space of their own.

“I recognised an unmet need: the youth,” Perry said. “From that moment, we knew we had to create a space just for them.”

The result was the creation of biennial youth workshops that balance community building and rigorous science.

This year’s event, titled ‘The International LFSA Youth Workshop 2025’, was held in Boston, Massachusetts in the United States last month.

It brought together young people, families and health experts, who engaged in storytelling, science and support for three days.

Among the young people invited to the workshop was Lakita. Unfortunately, she could not travel to the United States since she was in India, seeking treatment.

For the attendees, the experience was immersive. They attended DNA workshops with the guidance of genetic counselors and went on lab tours with doctors, including Dr Kornelia Polyak.

They visited the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Cancer and Blood Disorders Centre at the Boston Children’s Hospital.

They also shared their experiences of life with LFS and learned about the condition in small mentoring groups.

“Meeting people like me is the biggest thing I will take home,” one attendee said.

Parents like Joyce who attended the workshops had their own sessions tailored to help them learn about managing the condition in their children.

Further, they talked about the unique challenges of helping children with LFS transition to adulthood under the guidance of Dr Brandy DeRosa and DFCI senior genetic counselor Kathy Schneider.

“It was the most caring, warm and welcoming experience. It felt like a family reunion, even though it was our first time,” one parent said.

The LFSA Africa Chapter is led by Kenyan scientist Samuel Omolo, PhD researcher at the Pan African Institute of Genomic Sciences.

He has been coordinating with the LFSA US Chapter on how to accelerate awareness and advocacy of this rare hereditary disorder.

“At the moment, I have been studying this rare syndrome and genetic predisposition in Africa to understand the inheritance patterns, founder gene, prevalence rate in Africa and how to increase advocacy by involving like-minded researchers from different African countries,” Omolo says.

He adds that the biannual LFSA Youth Workshop organised by LFSA US Chapter has been of great help in offering more information to LFS families and researchers for awareness purposes not only in the US but also other countries around the globe.

It is estimated that about 1,000 families the world over have LFS, meaning that geographical distance is a major barrier to community support.

People like Lakita usually have to rely on a small circle of family and friends for emotional and financial support as they fight cancer.

Therefore, workshops that bring them together go a long way in showing them that they are not battling the condition alone.

More importantly, they have the opportunity to gain up-to-date knowledge on the management of the condition from experts.

“Every workshop is not just about information, it is about transformation. Our youth are not only patients, they are future scientists, doctors and advocates. They are the reason we continue to push forward,” LFSA president Jean Perry says.

Joel Magu is a freelance health journalist and media consultant who campaigns for more tools in public and private health facilities to fight cancer in early stages