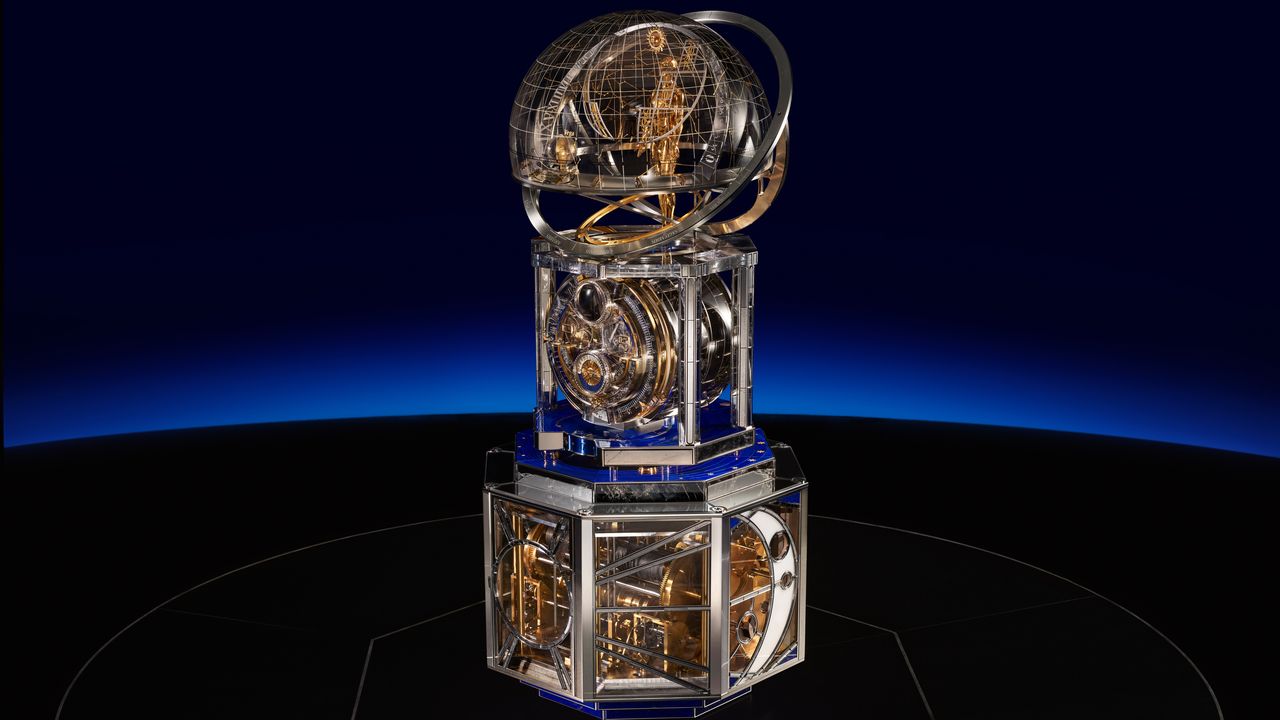

On 17 September 1755, Jean-Marc Vacheron laid the foundations of Vacheron Constantin. Today, the Swiss watchmaker celebrates 270 years – a milestone that few in the world of haute horlogerie can claim. To celebrate, the watchmaker is unveiling an extraordinary creation at a special exhibition in the Louvre, an institution renowned for its decorative arts and cultural heritage. The magnum opus piece of the exhibition is La Quête du Temps, a monumental astronomical clock created especially for the anniversary. Seven years in the making, it contains 6,293 mechanical components and twenty-three complications, making it one of the most ambitious pieces ever produced by the watchmaker.

Alain Costa

Over a metre tall, this clock is a true labour of love – the result of a rare collaboration between watchmakers, artisans, casemakers at L’Épée, engineers, astronomers and the celebrated automaton-maker François Junod. Together, they advanced the limits of horology to new heights, creating a piece that blurs the line between science and imagination. “With La Quête du Temps we wanted to push the boundaries of watchmaking by combining horology with the world of automata. What began as an idea and a few sketches quickly became an adventure – an extraordinary collaboration between watchmakers, artisans and craftsmen,” says Christian Selmoni, Style and Heritage Director at Vacheron Constantin.

This genius creation is presented alongside a series of historical artefacts drawn from across civilisations, revealing how timekeeping has always been a form of artistry and science. Case in point: a 10th-century automaton clock in the form of a peacock, likely produced at the caliphal court in Cordoba. Part of a larger mechanism, its beak may once have released pellets to mark the hours, reflecting the exchange of knowledge between Hellenistic traditions and Islamic scholars. Another treasure is a Ptolemaic water clock from Egypt, dating to the 3rd century BC. Designed to drip water at a steady pace, its inner walls were inscribed with months, solstices and equinoxes – an object that was both functional and cosmological. Elsewhere, a rare spherical watch bearing the signature of 16th-century French horologist Jacques de la Garde is also on display. Crafted in iron and brass and dating back to 1551, this is the oldest clock to be both dated and signed in France, making it a significant piece in documenting France’s watchmaking history.