By Sam Quinones

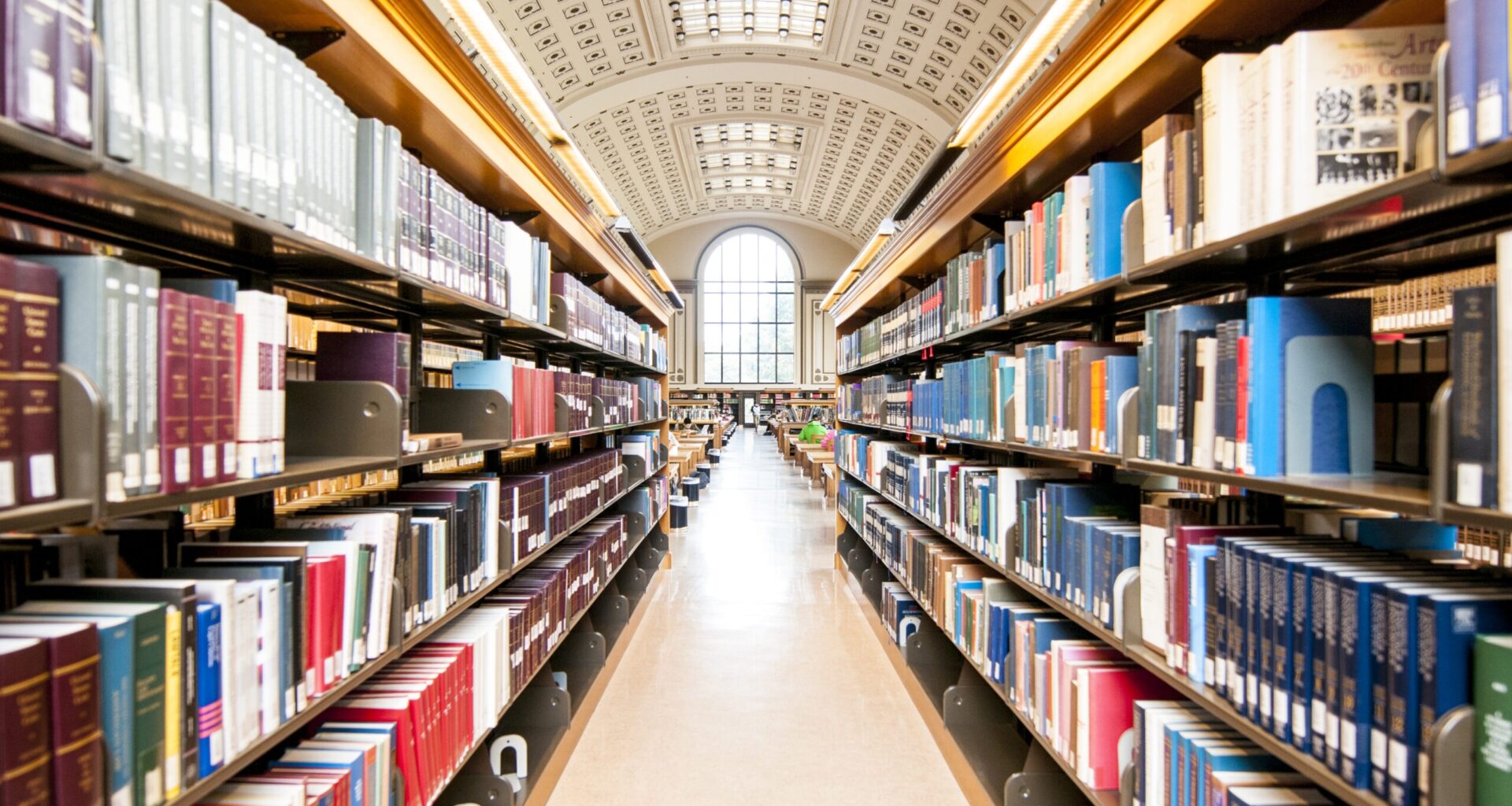

After years spent chronicling America’s opioid crisis in critically acclaimed books Dreamland and The Least of Us, journalist Sam Quinones turns to a subject that offers relief from the darkness: the tuba.

In his subjects’ devotion to the tuba, Quinones realizes he found a “mirror opposite of addiction.” a reminder that music and dedication can stitch people together where drugs and violence tear them apart. He traces the instrument’s unlikely history and revels in its cultures, from Mexican brass bands to orchestral pit sections, while also chasing legends of the “perfect tuba”—a kind of Stradivarius of the brass world. But ultimately, Quinones is less interested in the holy grail of tubas than in the people who play, build, and love them, whether it’s tuba-slinging narcoballadeers or members of the marching band.

Threaded through is a personal note from his Cal days in the 1980s: Quinones sees the tuba as a vessel of the punk rock ethos he first absorbed as a Berkeley student and has carried ever since—an embrace of the unglamorous, the defiant, and the deeply communal.

—Pat Joseph

By Scot Danforth

Ed was the first. The first student with severe disabilities to attend Cal. The first to head up California’s Department of Rehabilitation, the largest of its kind in the nation. And the first to lead the Center for Independent Living (CIL), which espoused the then-radical idea that disabled people were capable of making their own choices.

At the same time, let it be noted: Ed Roberts wasn’t exactly CIL’s first director. He wasn’t even in town when the organization opened its doors in a small apartment near campus in 1972; Ed, a rising political star, was pursuing teaching and networking opportunities elsewhere at the time. He assumed leadership of the newly formed group only after returning back to town.

From the start, this biography of Roberts, who died in 1995, takes pains to avoid what author Scot Danforth, a professor at Chapman University, calls the “folk hero mythology” surrounding the figure some have dubbed the “Martin Luther King Jr. of disability rights.” Danforth, a special education teacher–turned–scholar, fleshes out the real story of the Burlingame boy who overcame polio, then discrimination, to live his life to the fullest.

What emerges is the story of an independent man who was also entirely dependent on his community, including fellow activists like Judy Heumann, MPH ’75, Joan Leon, and Hale Zukas ’71. Danforth honors their stories too. After all, it was only together that they were able to force the suits in Washington to start paying attention to their demands, culminating with passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990.

Today, historic Medicaid cuts threaten to undo their achievements. The struggle continues.

—Esther Oh

By Mike Alvarez Cohen

Here is an insiders’ account of how UC Berkeley went from proverbial ivory tower to veritable IPO launching pad.

It’s no secret that Berkeley, as a revered public institution, has long been ambivalent about entrepreneurship and venture capital to a degree that its rival Stanford never was. For decades, the campus wrestled with the risks of corporate entanglements (recall the dustups over campus arrangements with Novartis and BP?) and the fear of getting too fully in bed with industry.

This book charts how those tensions played out over time and how Berkeley ultimately built a formidable innovation ecosystem of its own—SkyDeck, BEGIN, the Berkeley Startup Cluster, RADLab, RISELab, … the list goes on—meant to keep startups close to campus and tied to its public mission.

The success of the experiment is not widely known, but the book stresses it upfront: Berkeley now boasts more VC-funded startups by undergraduate alumni than any other university, not to mention faculty-founded unicorns like Databricks.

While the tone here is often more boosterish than critical, there are nods to the hazards: not all innovation is progress, and commercialization can crowd out basic research if left unchecked.

Startup Campus is more prospectus than narrative—fitting, perhaps, for a culture where pitch decks are the coin of the realm. Nonetheless the book offers a useful chronicle of a great public university adapting to a world that celebrates disruption even as it tries to stay true to its founding values of research, education, and service.

—P.J.

By Annalee Newitz

The year is 2064. California has seceded from the United States, and the nascent country is still reeling from the chaos of the war. Meanwhile in San Francisco, a crew of eclectic, military-trained robots has been left to their own devices in an abandoned ghost kitchen. Emboldened by newly granted civil rights from the California government, the bots reboot their lives in classic Bay Area form: by opening a noodle shop.

So begins Automatic Noodle, the latest novella from Annalee Newitz ’89, Ph.D ’98, science journalist and science fiction author of several other books including the Nebula Award-nominated novel The Terraformers. In many ways, Newitz’s near-future San Francisco resembles today’s city, with not-so-subtle nods to AI anxieties, queer identity, and the modern-day immigrant experience. The four misfit robo-restaurateurs face “robophobia” and the ever-looming threat of bad reviews as they struggle to find their place—and master the very human art of biang biang noodles—amidst the Bay’s less than bot-friendly environment.

It is, in the words of KQED’s Alexis Madrigal, “The most San Francisco book that has ever been or could ever have been written.”

Automatic Noodle is also a testament to the author’s keen understanding of California. Their novella explores the state’s many contradictions—its fringe, yet omnipresent secessionist history, a growing conflict between desires for automation and authenticity, and the eternal tension between techno-libertarian and kumbayaish progressive sensibilities. It’s a lot to cover in a quick 163 pages, and the story can, at times, feel a bit too neat. But there’s something sweet about the plight of the robots—and their vision for a robot-filled future.

“What if robots were just your neighbors and regular folks, and they weren’t super masterminds who turned you into a paper clip?” Newitz wondered in a recent interview. “What if they were just trying their best, like all of us?”

—Leah Worthington

U.C. Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics

How can psychedelics help with post-partum depression? Do shrooms extend our cellular lifespan? What might psychonauts learn from Buddhists?

These are just a few of the questions posed by the authors of The Microdose, an independent journalism newsletter from the Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics. For the last four years, the twice-weekly (free) substack has been at the forefront of the hallucinogen renaissance, highlighting the latest drug research, policy, and expert analysis.

Spearheaded by big-shot science journalists like Michael Pollan and Jane C. Hu, Ph.D ’14, The Microdose takes an objective approach to the world of psychedelia, reporting on it much like any other industry. As Pollan wrote at the publication’s launch in 2021: “Psychedelics is not yet a full-blown journalistic beat but it deserves to be one, and Berkeley aims to help make that happen.”

The newsletter offers something for everyone. There are colorful first-hand accounts of a psychedelics conference, interviews with industry voices like the founder of Sex & Psychedelics magazine, and the slightly clickbaity analysis, “What do we know about Luigi Mangione’s interest in psychedelics?”

Short, sweet, and well-researched, the newsletter is exactly what it sounds like—your perfect weekly dose of psychedelia, hallucinations not included.

—L.W.

By Barry Bergman

A disaffected film buff tries on working-class heroism in this vivid debut by a former staffer (The Berkeleyan and Berkeley News) and contributor to California magazine.

Simon Bussbaum flees Queens for an Arizona copper smelter, inspired by a radical labor film and visions of solidarity. What he finds instead is grueling work, casual misogyny, and the uneasy comedy of leftist dreamers out of their depth. The opening riff on Pauline Kael signals the book’s Berkeley pedigree, and Bergman—himself a onetime smelter worker—renders the industrial inferno with visceral detail: “The stacks, smoking under the moon and stars, were a disquieting vision of end times…the ruins of a lost civilization.”

If some characters verge on stereotypes, the novel succeeds as a tough-minded meditation on politics, delusion, and survival in Nixon’s America. A gritty, darkly funny coming-of-age steeped in radicalism and copper dust.

—P.J.

Related