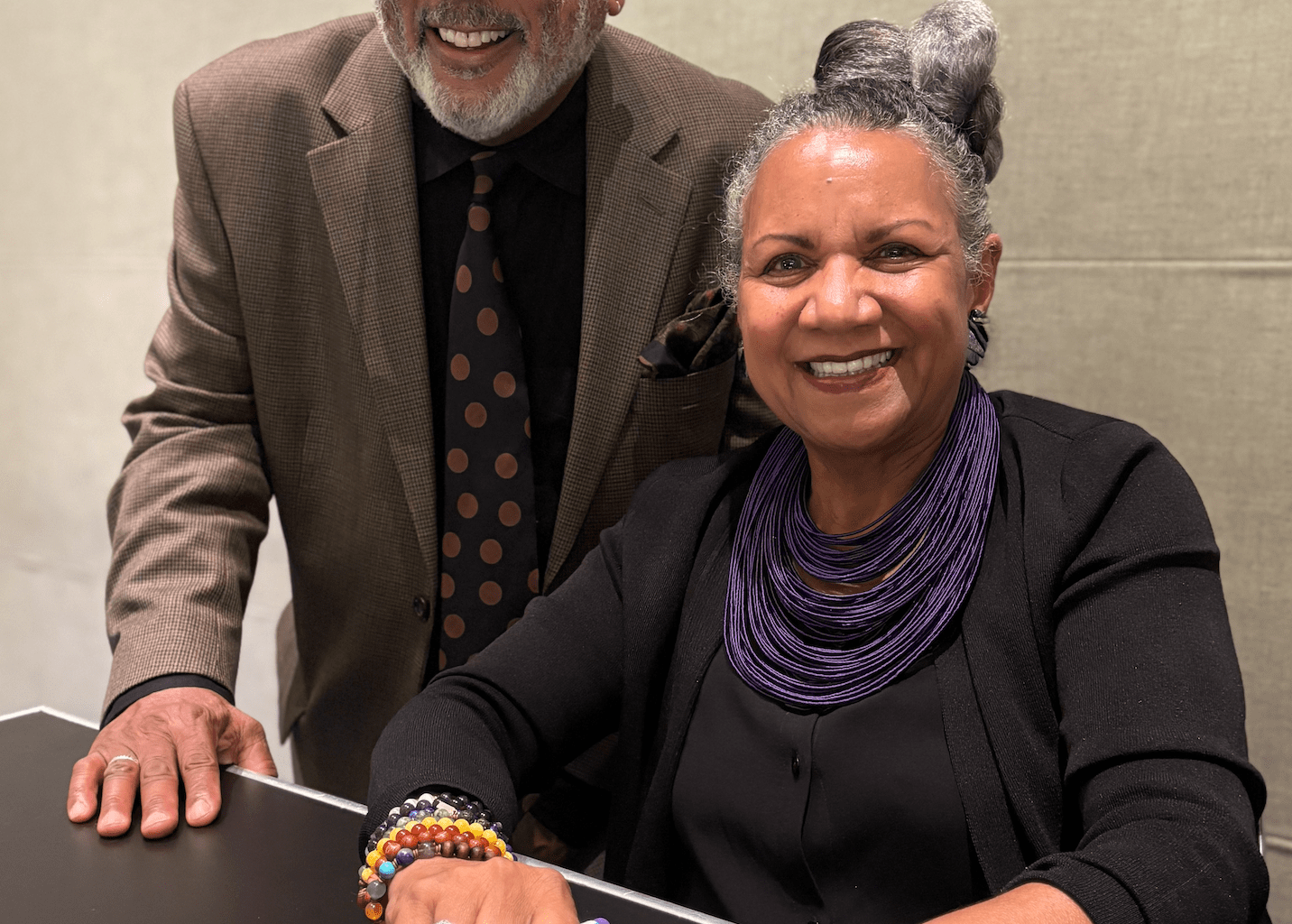

There was a full house at the Segal Theater of CUNY’s Graduate Center (Fifth Avenue at 34th Street) last Tuesday, for an illuminating discussion of A’Lelia Bundles’s latest book, “Joy Goddess, A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance” (written with L’Alelia Perry Bundles). The event, at the one-time Gilded Age B. Altman Department Store Building, featured biographer Eric K. Washington (@erickwashington), 2015–16 Leon Levy Biography Fellow and author of “Boss of the Grips,” and Bundles (@aleliabundles), author of “On Her Own Ground,” founder of the Madam Walker Family Archives, and former NBC/ABC News producer.

Their exchange showcased a shared enthusiasm for the history and lore of Harlem, the place identified for the past century as America’s Black Cultural Capital. An hour seemed to collapse into 15 minutes as both held an attentive audience transfixed.

Michael Henry Adams photos

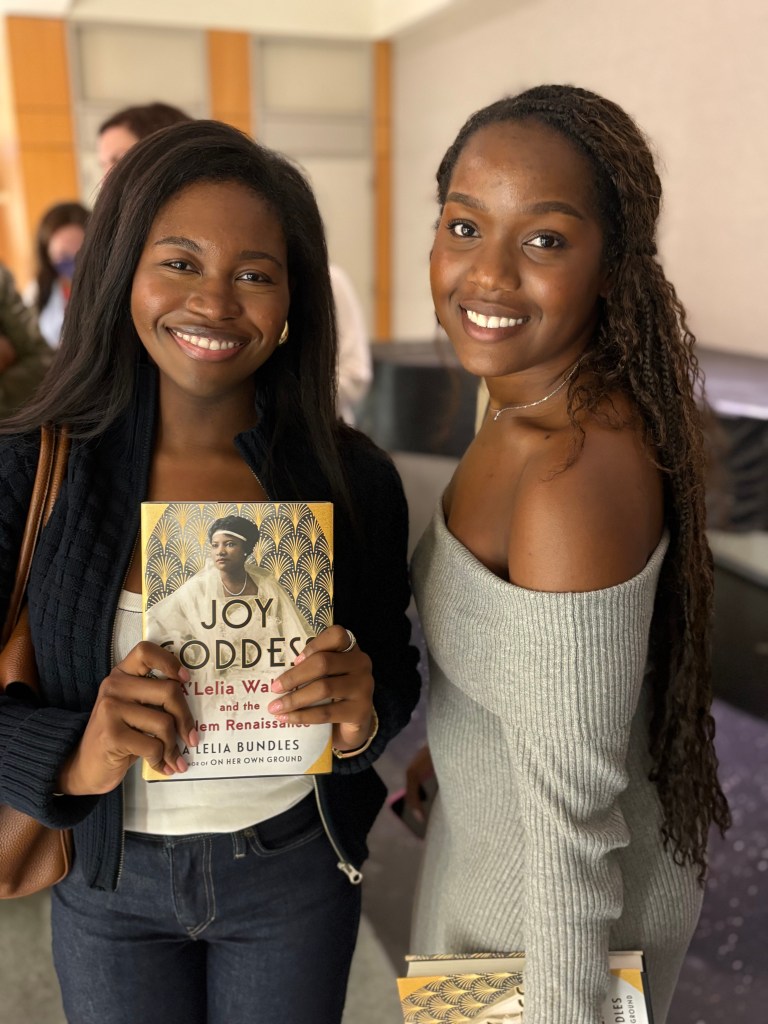

Munachi Onyiuke and Olivia Greenaway, Columbia University MPH candidate, get their books signed.

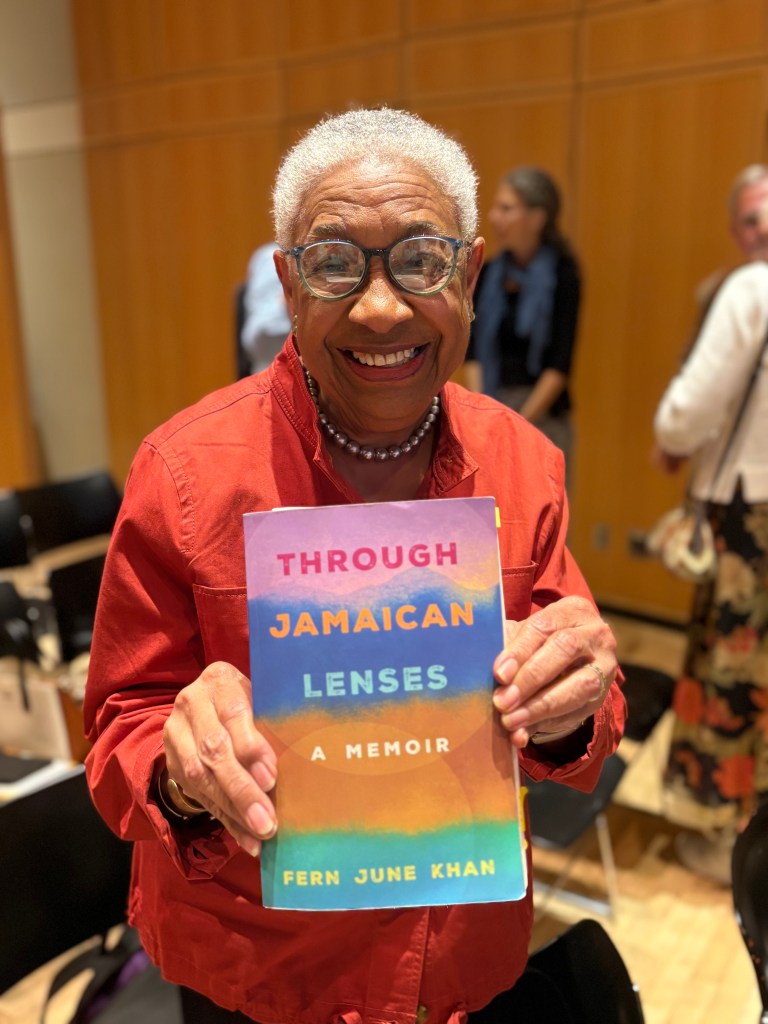

Munachi Onyiuke and Olivia Greenaway, Columbia University MPH candidate, get their books signed.  Fern June Kahn holds up her new memoir, “Through Jamaican Lenses.”

Fern June Kahn holds up her new memoir, “Through Jamaican Lenses.”  Historian David Levering Lewis, who wrote “When Harlem was in Vogue” about the Harlem Renaissance 40 years ago, greets Pamela Newkirk and Judith Byrd and was acknowledged by A’Lelia Bundles at program’s start.

Historian David Levering Lewis, who wrote “When Harlem was in Vogue” about the Harlem Renaissance 40 years ago, greets Pamela Newkirk and Judith Byrd and was acknowledged by A’Lelia Bundles at program’s start.

Daughter of millionaire beauty-care manufacturer Madam C.J. Walker, A’Lelia Walker was dubbed by poet Langston Hughes the “joy goddess of Harlem’s 1920s.” Glamorous but down-to-earth, Walker was the author’s great-grandmother and namesake. Captivating public notice due to her unique position as America’s first high-profile heiress of African descent, she emerged as a convener of Black artists and prominent white patrons of the arts, on festive occasions and especially at parties. These erstwhile mere social events were as legendary for their sophistication and uproarious fun as they were for their purposeful intent: to encourage and fund Black creative genius.

Speaking with Washington, Bundles explained how her mission was to reveal the forgotten complexity of her great-grandmother, someone she said sometimes previously,= had been caricatured as a frivolous party girl.

“Although Madame Walker was born after emancipation, her story was often reduced to a tale of from slavery and rags, to millions. It was: ‘Madame Walker made the money and A’Lelia Walker spent it,’” Bundles said. “Her legacy is far, far greater. By helping to identify, [and] entertaining, engaging, and assisting people who became her era’s social and intellectual luminaries, like Zora Neale Hurston (writer), Paul Robeson (baritone), Florence Mills (star Broadway singer), Justin Sandridge (concert pianist), or Richmond Barthe (sculptor), she helped define the Harlem Renaissance,” Bundles told Washington.

I asked why, after Vertner Tandy’s saved the Walker women so much money by remodeling two existing houses on 136th Street into their elegant new townhouse, she refrained from mentioning the early Black architect’s effort to do the same thing, by renovating “Bishops Court” in Flushing, Queens, as their country house. I was glad for Bundles’s answer: “I covered that earlier in my biography of Madame Walker. Here, I wanted to emphasize A’Lelia.”

The crucial response to the night’s most cogent question held even greater satisfaction. Washington asked, “What would the Walker women have to say today, about efforts to diminish Black contributions to America’s greatness?” Their very lives, Bundles suggested, starting from nothing, overcoming foul play and obstacles to obtain success, would be their response: “Their example is the very definition of accomplishing American greatness!”

Like this:

Like Loading…

Related