Main findings

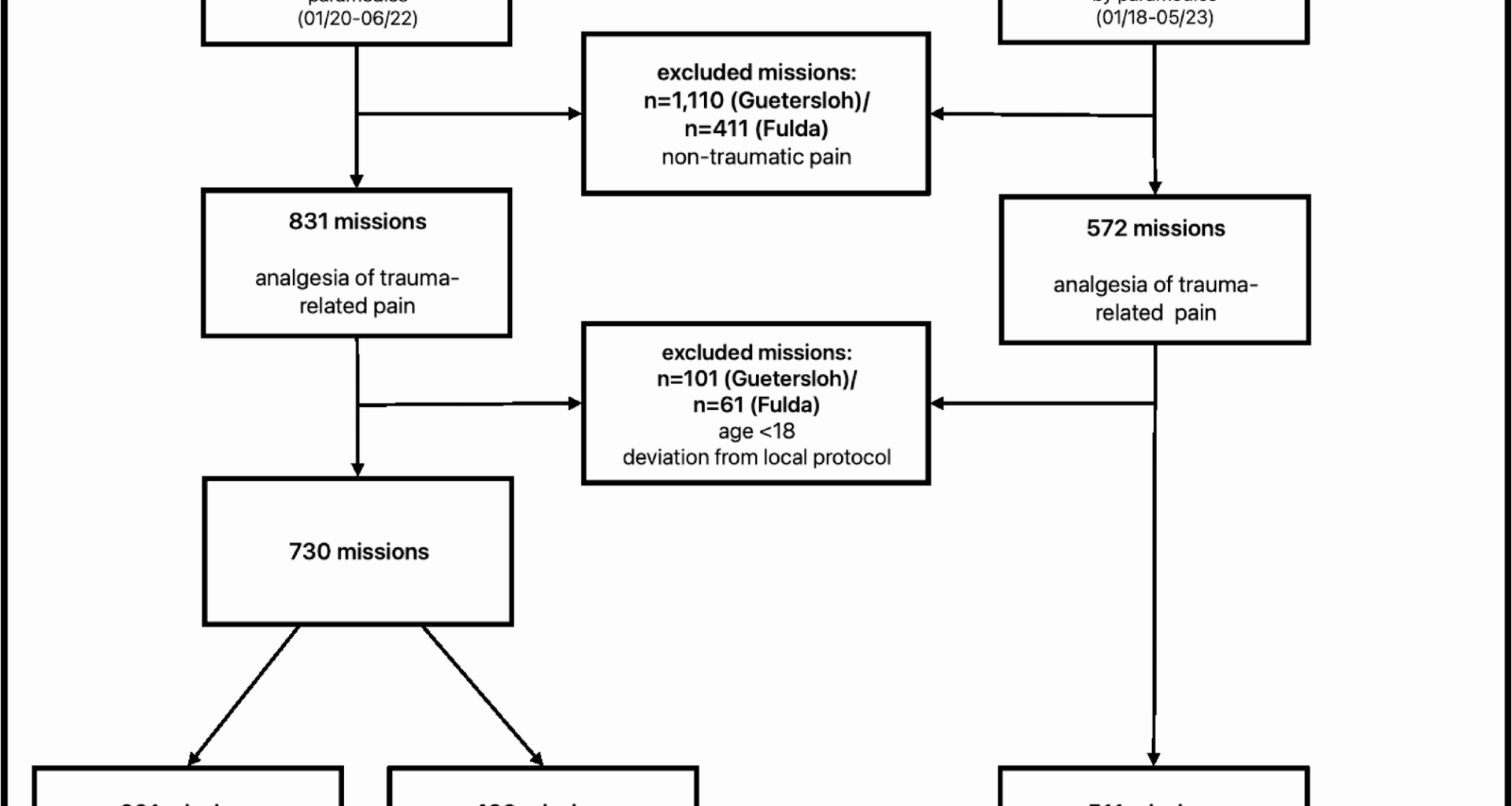

This retrospective, multicenter observational study evaluated the efficacy and safety of analgesic therapy for trauma-related pain. In contrast to monotherapy with paracetamol or piritramide, treatment with nalbuphine plus paracetamol increased the likelihood of achieving NRS ≤ 4 on admission to the hospital. Treatment-related complications were rare, mainly related to nausea and/or vomiting, and did not differ between the opioid analgesics used.

Prehospital analgesia for trauma-related pain

Adequate prehospital analgesia after traumatic injuries is a decisive quality criterion for emergency medical care [14,15,16]. Despite negative effects associated with the physiological pain response, these patients continue to be inadequately treated with analgesics, often out of concern for potentially life-threatening adverse effects [5, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. International studies have frequently evaluated the use of fentanyl, morphine and/or (es-)ketamine for prehospital analgesia of trauma-related pain and are therefore also recommended in international guidelines [24,25,26,27]. Studies investigating the analgesic effect and safety of piritramide, which is widely used in German-speaking countries, and of a combination of nalbuphine plus paracetamol administered by paramedic are still lacking.

Owing to the changes in the legal basis in Germany, strategies for the implementation of optimal prehospital analgesic therapy by paramedics are still a topic of international controversy and debate. Arguments against piritramide and nalbuphine plus paracetamol often include their lower analgesic potency compared to strong µ-opioid receptor agonists such as fentanyl, as well as the withdrawal symptoms potentially caused by nalbuphine in patients receiving preexisting opioid therapy. However, the advantages of nalbuphine are its favorable pharmacokinetics and a lower rate of life-threatening complications [8]. The present analysis provides evidence for the analgesic efficacy and safety of prehospital analgesia by paramedics using both piritramide and nalbuphine plus paracetamol. The application of nalbuphine plus paracetamol appeared to be particularly suitable for achieving NRS scores ≤ 4 at hospital admission, despite initially comparable pain levels.

There are several possible reasons for this: Firstly, piritramide and nalbuphine have almost identical analgesic potencies of 0.7‒0.75 and 0.7‒1.1 morphine equivalence, respectively, and comparable durations of action of approximately 3–6 h. However, the main differences between the two substances lie in the time to onset of action (piritramide ≤ 16.8 min; nalbuphine ≤ 3 min) and the time from onset of action to peak effect (piritramide ≤ 45 min; nalbuphine approximately 10 min). Owing to these pharmacokinetic peculiarities, it is possible that comparable prehospital analgesia cannot be achieved to the same extent by piritramide during the average durations of an ambulance transport to the hospital [28,29,30]. Secondly, while an average total dose of 14.2 ± 5.9 mg nalbuphine was administered, a significantly lower total dose of 7.1 ± 3.5 mg piritramide was administered. It is therefore possible, that a comparable analgesic effect could have been achieved by administering increased doses of piritramide, provided that the different pharmacokinetics would not lead to a relevant prolongation of prehospital care time or an increase in complication rate. In this context, the ceiling effect of nalbuphine is an advantage that provides a high degree of safety regarding respiratory complications, which makes slow titration unnecessary [31, 32].

Furthermore, while paracetamol, as known from the literature, was not shown to be as effective as a single substance in the present study [1, 3, 33, 34], data concerning its use as a co-analgesic show inconsistent results [35]. While an opioid-sparing effect of paracetamol could not be proven in emergency rooms [36], studies in perioperative medicine have revealed both a reduction in the need for opioids and a lack of an additive effect [37]. The additive administration of paracetamol in the present analysis could have enhanced the analgesic effect of nalbuphine. Despite the heterogeneous data, this additional effect may also manifest in combined analgesic therapy with piritramide and paracetamol.

Possible effects of prehospital analgesia with nalbuphine on the clinical course

Although the present results demonstrate that analgesic therapy with nalbuphine plus paracetamol is effective and safe in trauma patients, its pharmacodynamic properties as a partial µ-antagonist/κ-agonist regularly raise concerns about potential impairments and interactions in the context of further medical care. These discussions include possible interactions with subsequent µ-agonists (e.g., morphine, fentanyl, and sufentanil), for example, in the emergency department or during further surgical treatment in the hospital. Although nalbuphine exhibits partial µ-antagonism with up to 1/3 the potency of the µ-antagonist naloxone, the data regarding the possibility of administering µ-agonists following nalbuphine administration are inconsistent: While some studies report no adverse effects during treatment in the emergency department [36, 38], others suggest a need for increased doses of µ-agonists post-nalbuphine without any increase in drug-related complications (e.g. hypotension, bradycardia, hypoventilation) [39, 40]. Whether and, if so, to what extent prehospital analgesia with nalbuphine as a partial µ-antagonist could influence the general anesthesia required for surgical treatment has not yet been sufficiently evaluated. However, there is the possibility of displacing the partial µ-antagonist nalbuphine through competitive agonism with a µ-agonist. In this context, remifentanil appears particularly suitable because of its short duration of action and short context-sensitive half-life, with minimal risk of accumulation and remorphinization after the effects of nalbuphine have subsided. From a clinical perspective, there are currently no significant concerns regarding the use of nalbuphine in prehospital emergency care, provided that subsequent treating physicians are informed about its administration and can adjust their choice of analgesics accordingly. Future studies should evaluate the implications of prehospital nalbuphine administration for in-hospital and perioperative care.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First of all, the retrospective observational design limits the ability to infer casual relationships and introduces potential selection and documentation bias. Systematic differences between the observed regions and the lack of available data on exact mission and transport times may act as potential confounding factors. Although both study regions are comparable in terms of their rural character and EMS structures, variations in prehospital duration and transport durations may still have influenced the degree of pain relief observed at hospital admission and could have influenced the observed differences between the analgesics used. Furthermore, the comparison of the piritramide and nalbuphine plus paracetamol groups was based only on patients with an initial NRS score of ≥ 7, due to the limitations of the matched-pairs design and the resulting missings, limiting the exploration of outcomes in patients with lower initial pain scores. While the use of the NRS for evaluating pain intensity is controversial because of its subjectivity, it allows a simple and practical evaluation of the indication and effectiveness of analgesia, which is why it is recommended by professional societies and widely used in (pre-)hospital settings. Furthermore, the effectiveness and complications of the analgesic concepts investigated could not be assessed over time, for example, in the emergency department or during surgery. Despite this, the results provide important insights into the development of treatment options for trauma-related pain that are associated with minimal complications and high efficacy.