Today, cricket has become synonymous with politics between India and Pakistan. It was not always so.

In 1947, as the two countries were brutally divided, it was not only the military or police who split, but sportsmen too. India and Pakistan first played as independent nations in 1952, with Vinoo Mankad captaining India and Abdul Hafeez Kardar leading Pakistan. Just six years earlier, Kardar had played for India, where he and Mankad had been part of the same side. This was another reality of Partition.

Other Pakistani players such as Amir Elahi and Gul Mohammed had also represented India before 1947 but switched allegiance after independence. The first match between the two new neighbours took place in 1952-53, hosted by India. A return series followed in Pakistan in 1954–55. Thus began cricketing rivalry between the two countries, and, in parallel, the politics.

Politics did not take centre stage until the 1980s, when militancy erupted in Kashmir and the Khalistan movement took root in Punjab. Even then, soft diplomacy – free movement of players and artists – continued, while terrorism and Kashmir remained on a separate track.

That was the golden era of cricket in the subcontinent.

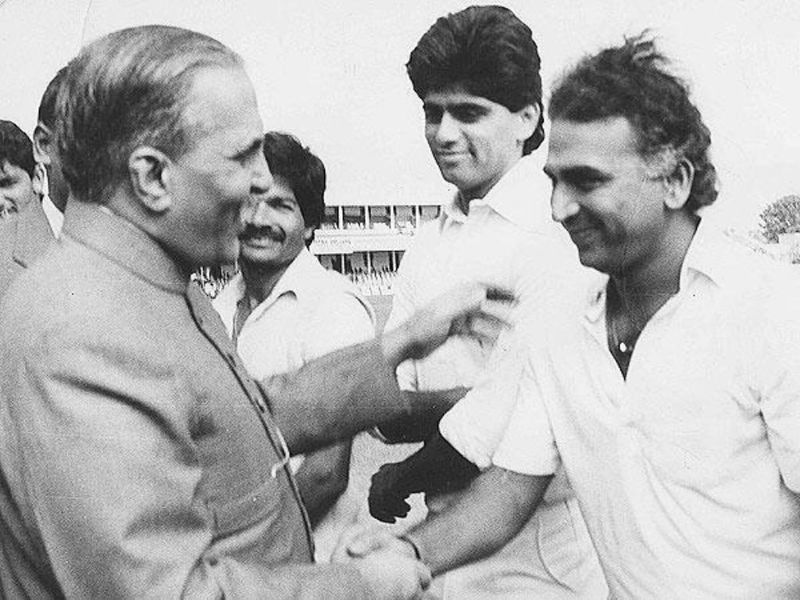

In February 1987, Pakistani president Zia-ul-Haq landed in Jaipur on an invitation from the BCCI to watch a friendly match, even as tensions soared over Operation Brasstacks, which had triggered nuclear fears on both sides. The most memorable moment was the image of India’s captain, Sunil Gavaskar, shaking hands with Zia.

Pakistan’s team was captained by Imran Khan, later prime minister, who at the time was a heartthrob in India. He even appeared in a joint advertisement with Gavaskar. Back in Delhi, Rajiv Gandhi and Zia held a bilateral meeting on the sidelines, seeking to calm frayed nerves over Brasstacks.

In the 1980s, Indians were used to seeing giant hoardings of Khan and Gavaskar in Mumbai’s Marine Drive and Kolkata’s Chowringhee, as well as on the back covers of glossy news and fashion magazines. They campaigned jointly for Thums Up, while Khan also modelled for Cinthol soap.

The year 1983 was a watershed for Indian cricket. That summer, the “backbenchers” of world cricket stunned the sport by winning the Prudential Cup in England. India beat the all-conquering West Indies, led by Clive Lloyd and boasting Vivian Richards and pace bowler Malcolm Marshall, at Lord’s.

That October, India played the West Indies in Kashmir. The Indian team, fresh from its World Cup triumph under Kapil Dev and featuring stars such as Gavaskar, Ravi Shastri, Krishnamachari Srikkanth, Syed Kirmani, Dilip Vengsarkar and Roger Binny, was heckled throughout. It became an international embarrassment. Many Kashmiris in the stands waved posters of Imran Khan and cheered for Pakistan. Gavaskar, batting at the time, responded with a thumbs-up – an allusion to the Thums Up advertisement.

During the lunch break, a mob breached the security cordon and attempted to tamper with the pitch. They were later arrested, but cases dragged on until their release in 2011. That incident marked the beginning of cricket as politics.

The 1990s brought another turn. For a decade, neither side toured the other. Shahryar Khan, a former Pakistani foreign secretary, became head of the PCB in 1999 and pushed cricket as diplomacy. That year, Nawaz Sharif and Atal Bihari Vajpayee met at the SAARC summit in Colombo and agreed to restart the Composite Dialogue. Both nations had just tested nuclear weapons, flexing geopolitical muscle. But Pakistan succeeded in persuading India to host a match in Mumbai.

In India, however, the rise of political Hindutva complicated matters. The demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 was followed by the Bombay blasts of 1993, orchestrated by Dawood Ibrahim, who later moved to Pakistan. In 1999, India and Pakistan met at Delhi’s Feroz Shah Kotla stadium (now Arun Jaitley stadium). The match had to be postponed more than once after Shiv Sena activists caused disruptions.

The next iconic clash came in April 2005, when Pakistan’s president, Pervez Musharraf, travelled to Delhi to meet the Indian prime minister, Manmohan Singh. The two sides faced each other again at Kotla. Musharraf later wrote in his memoir, In the Line of Fire, that as a cricket fan he had been tempted to leap with joy at Shahid Afridi’s bowling.

Today, cricket has become synonymous with politics between India and Pakistan. Bilateral talks have ground to a halt, while New Delhi continues to press its case that Islamabad is a state sponsor of terror.

Shome Basu is The Wire’s consulting photograph editor.

This article went live on October second, two thousand twenty five, at three minutes past three in the afternoon.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.