Design, participants, and operational definitions

This prospective observational cohort study was conducted from July 15, 2024, to January 19, 2025. Eligible participants included patients of any age and sex who were admitted to the neurosurgical departments at the European Gaza Hospital (EGH) and Nasser Medical Complex (NMC) due to war-related TBI.

Patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 3 and bilaterally fixed, dilated pupils were classified as “code black” at triage. They typically died shortly after arriving at the emergency department. Due to the collapse of medical documentation systems under wartime conditions and the overwhelming patient load, these cases were not reliably recorded, leading to significant missing data. Consequently, they could not be included in the study cohort. The study also excluded individuals with injuries unrelated to the war.

War-related Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) was defined as brain damage secondary to an externally inflicted trauma such as explosive blasts, blunt trauma, or penetrating injuries [17].

TBI severity was classified based on the presenting GCS as follows: mild (GCS scores of 13–15), moderate (GCS scores of 9–12), or severe (GCS scores ≤ 8) [18, 19].

Concomitant injuries were defined as those that required hospital admission on their own merit, independent of the TBI.

Complications included adverse events that occurred during hospitalization and up to 30 days after admission, such as brain abscess, wound infections, meningitis, CSF leaks, hydrocephalus, and rebleeding.

Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) was categorized on a scale from one to five as follows: one = death, two = persistent vegetative state, three = severe disability (dependence on others for daily support), four = moderate disability (independent in daily life but with some residual deficits that interfere with complex activities), five = good recovery (resumed normal activities even if some minor neurological or psychological deficits may still be present) [20].

Neurological deficits upon discharge refer to new focal or generalized neurological impairments identified at the time of hospital discharge, and they are classified into the following categories: language deficits, unsteadiness, visual deficits, impaired consciousness, facial asymmetry, irritability/confusion, sensory deficits, and motor deficits.

Study settings and trauma care infrastructure

Before the current war, Gaza’s neurosurgical services were already strained by ongoing shortages, weak infrastructure, and limited ICU capacity. Two main departments at Shifa Medical Complex and EGH provided essential neurosurgical care, staffed by four board-certified neurosurgeons, seven master’s-level physicians, and 15 residents, and hosted the local neurosurgery board program [21, 22]. Despite these challenges, these centers performed procedures such as VP shunts, tumor resections, spinal surgeries, and emergency craniotomies with outcomes approaching international standards [21, 22].

The war profoundly disrupted these services. Shifa Medical Complex was destroyed early in 2024, and EGH was attacked and later occupied, becoming inoperable since May 2025 [23]. By mid-2025, only two board-certified neurosurgeons, four master’s-level physicians, and 12 residents remained in Gaza. Neurosurgical care became fragmented and mainly focused on treating war injuries. Israeli military operations also split Gaza into two isolated zones, north and south, making medical referrals between them impossible [8]. The neurosurgical departments featured in this study represented the most advanced units in the southern enclave at that time, located at EGH and Nasser Medical Complex (NMC). EGH hosted the last functional board training program and employed the only two remaining board-certified neurosurgeons in the Strip, along with eight residents and two master’s-level specialists.

Prehospital care for trauma patients was nearly nonexistent due to the collapse of ambulance services and ongoing hostilities; most patients were transported by civilians without stabilization. In the emergency department, rapid triage was performed under mass casualty conditions, with immediate focus on airway management, bleeding control, and neurological assessment. Intubation was attempted when feasible, but ventilators were scarce and limited to ICU settings, leaving many patients dependent on manual bag-valve ventilation while waiting for ICU beds. During the study period, only 40 ventilator-equipped ICU beds were operational across the Strip, serving a population of over two million people [8]. Invasive ICP monitoring was unavailable, so ICP elevation was assessed clinically and through imaging. Tranexamic acid was not available, and osmotic agents (mannitol or hypertonic saline) were inconsistently accessible due to supply chain disruptions.

Upon admission, all TBI patients received standardized medical management: empirical antibiotic prophylaxis with ceftriaxone 1 g IV twice daily for adults (or 40 mg/kg for children), antiseizure prophylaxis with levetiracetam 500 mg twice daily or phenytoin 5 mg/kg, and omeprazole 40 mg daily (or 1 mg/kg/day for pediatric patients) for GI protection, along with analgesia. In cases of penetrating TBI, vancomycin 15 mg/kg IV was also administered.

Surgical decisions were made based on radiological findings and the patient’s clinical status. Decompressive craniectomy was performed for elevated ICP, acute subdural hematoma, and > 5 mm midline shift, with the dura left open to reduce pressure. In cases of epidural or extra-axial hematomas without significant edema, craniotomy and hematoma evacuation were carried out. Debridement with bone elevation, with or without dural repair, was used for depressed skull fractures with brain herniation, and EVD insertion was performed in cases of hydrocephalus.

Patients were discharged either to inpatient rehabilitation, which is available only at a single center in Deir Albalah in the Middle Governorate with very limited capacity, or to outpatient physiotherapy, depending on service availability and injury severity. Due to the severe deterioration of rehabilitation infrastructure in Gaza [2], many were sent home without structured follow-up, raising the risk of long-term disability and impaired functional recovery.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was the mortality rate within 30 days of admission. Secondary outcomes included neurological status at discharge, classified by the GOS and GCS scores, the presence of neurological deficits, and the rates of surgical complications.

Data collection

A trained fourth-year neurosurgery resident (the first author) collected the data using a standardized, Excel-based case reporting form. Data was gathered from bedside observations as well as from medical files, operative notes, and radiology reports. The information obtained at admission included patient demographics, such as age and sex, clinical data on presentation, including the chief presenting symptom, mechanism(s) of injury, admission GCS scores, computed tomography (CT) findings from formal radiology reports (MRI was unavailable), and the presence of concurrent injuries, along with laboratory parameters like hemoglobin level upon admission.

Collected information related to the clinical course included the need for ICU admission, total ICU and hospital stay durations, the requirement for surgical intervention, the types of interventions performed, and the occurrence of complications.

The 30-day outcome data (survival) were gathered during hospitalization and from neurosurgical outpatient clinic visits, which took place in a high-volume outpatient neurosurgical clinic with an average caseload of approximately 120 patients per session. Patients who missed their clinic appointments were contacted by phone to determine the primary outcome.

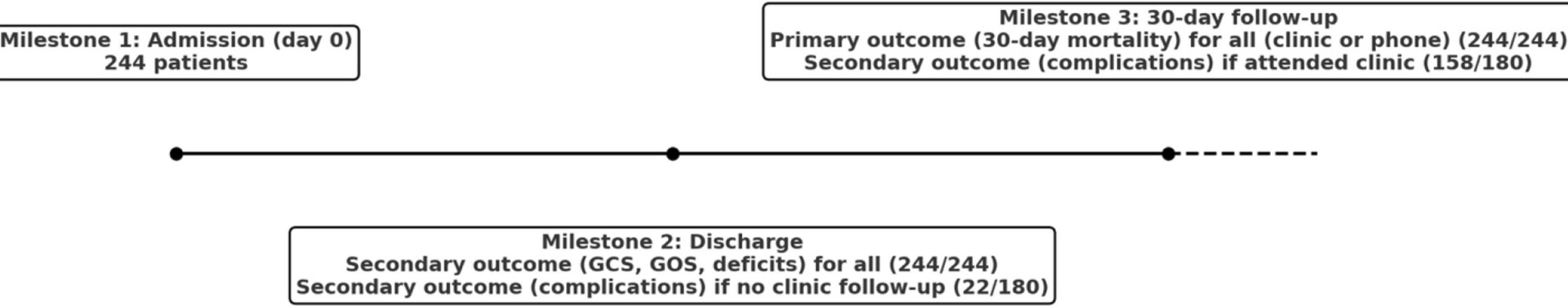

The secondary outcome (neurological deficits) was recorded at discharge and included the GOS scores, GCS scores, and the presence of neurological deficits. The other secondary outcome (complications) was documented during admission and at the 30-day outpatient visit. For survivors who did not attend the outpatient clinic, complications were reported up to the day of discharge. Figure 1 shows key milestones for data collection and outcome reporting.

Timeline of Outcome Assessment for Patients with TBI in the Cohort

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was granted by the Research Department at the Ministry of Health in Gaza. Additionally, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Islamic University of Gaza approved the study (approval letter number: 2024/06). Informed consent was obtained directly from patients or, for those with impaired consciousness, from their next of kin. All patient information was anonymized and securely stored. The methods and results reporting adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Checklist [24].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized the data: the shape and distribution were analyzed to report either the mean and standard deviation or the median and interquartile range for continuous variables, as appropriate; categorical variables were summarized as frequency and percentage.

Univariate comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test, Student’s t-test, chi-squared test, and Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Multivariable modified Poisson regression with robust error variances was employed to estimate adjusted relative risks (RRs) for the primary outcome. The model was adjusted for all relevant clinical covariates, including demographics, clinical features, and radiological findings. Basal cistern status, midline shift, and shrapnel presence were excluded from the model due to a high percentage of missing data (> 40%). A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R software.