In 2005, as a fledgling academic navigating the historical waters of industry policy, I sat across from my PhD supervisor, scribbling notes on Frank Stilwell’s model of capitalism. That framework – private ownership of production, laced with ideology and a state role that shapes markets – became my North Star for dissecting how governments and industries entwine. Little did I know then that two decades later, in 2025, those same dynamics would echo amid the rubble of a liberal economic dream, the notion that trading partners make peaceful ones.

Today, as drones fly back and forth over Eastern Europe and tariffs fly between Washington and Beijing, that ideal is fraying – not because free markets have failed, but because peace among great powers is no longer assured. Sovereign capabilities, long subordinated to economic liberalism, are clawing their way back to primacy.

None of this is new. It’s the eternal swing of history’s pendulum.

Amid the post-Cold War euphoria from the 1990s onward, globalisation’s architects like Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, and even John Howard, preached the ‘commercial peace’ thesis. Open borders, supply chains snaking across continents, and WTO rules would bind nations in mutual prosperity, rendering war obsolete. Australia, ever the eager disciple, signed free trade pacts from Singapore to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), slashing tariffs and welcoming Chinese investment in our ports and mines.

It worked, economically. GDP boomed, jobs flowed, and our ‘mixed economy’, or the pragmatic blend of coordinated and competitive capitalism that Stilwell had so deftly mapped out, thrived.

But geopolitics has a rude habit of upending theory.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Hamas’s rampage, and the South China Sea’s simmering cauldron remind us that great powers do not always play by market rules. When Xi Jinping eyes Taiwan or Putin redraws maps with tanks, the liberal calculus collapses. Trade becomes a weapon and export bans on rare earths and sanctions on semiconductors destroy the theoretical bridges to peace and prosperity.

This unravelling isn’t economics’ fault. Free markets remain the most efficient allocators of scarce resources, channelling Stilwell’s ‘expansionary tendency’ into innovation and growth. Australia’s lithium exports still fuel global batteries (not to mention our coal and iron ore – which never get a mention by the way), and there is still hope for our services sector.

But productivity is faltering under Labor’s state-led economic agenda with no national security benefits in sight.

The culprit is the return of uncertainty, that primal force John Mearsheimer warned of in his offensive realism. Without assured peace, interdependence breeds vulnerability. A just-in-time supply chain from Shenzhen to Sydney? Fine in 2010; folly in 2025, when a blockade could starve our factories. Sovereign capabilities – domestic production of essentials like steel, biochemicals, and yes, vehicles – reassert themselves not as protectionist relics, but as insurance against chaos.

History brims with precedents. Mercantilist empires hoarded bullion amid endless wars, the Smoot-Hawley tariffs of 1930 in the US (under Herbert Hoover, a Republican President), born of Depression-era fear, exacerbated but didn’t invent global fracture. We’ve been here before, cycling through liberal openings and security closures.

The novelty is our amnesia.

Andrew Hastie’s recent call to resurrect Australia’s car-making industry is far from radical.

Referred by some commentators as ‘nonsensical nostalgia’, such reports demonstrate a complete lack of understanding of historical industry policy processes and the impact of century-long industry policy legacies.

Hastie, one of the few Liberals demonstrating any sense of policy and whose China warnings deserve applause, argues for reviving Holden and Ford assembly lines to bolster our self-reliance. It’s a seductive pitch in this era of frayed alliances. Why buy everything from China when Beijing could choke the flow at any time?

Hastie’s critics demonstrate their profound misreading of history, ignoring the pragmatic approach both sides of politics have adopted toward automotive manufacturing since the 1920s. Hastie’s vision prioritises sovereign capability over economic liberalism. Given the automotive sector played such as major role in our defence in the second world war, that sector has been through waves of protectionism and reform since motor cars became available in Australia.

Australia’s car industry wasn’t born of free-market zeal but state paternalism, a habit as old as Federation. In the 1920s, amid post-world war one reconstruction, both Labor and conservative governments erected tariff walls to nurture local assembly. The 1922 British Preferential Tariff shielded emerging plants in Melbourne and Adelaide, with Labor’s Scullin administration in 1929 doubling down via import quotas to protect jobs against American imports.

This wasn’t ideology run amok, it was pragmatism, shielding infant industries in a vast, isolated market where shipping costs bit deep. By the 1930s, under Lyons’ United Australia Party, subsidies flowed via the 1939 Motor Vehicle Engine Bounty Act, blending nationalism with economic necessity. The second world war accelerated the fusion with Ford and General Motors helping to churn out tanks and planes, their factories nationalised in part under Curtin’s Labor wartime cabinet. Post-1945, Chifley’s government tried to nationalise private banks but spared autos, opting instead for a bipartisan approach that hiked duties to 45 per cent, ensuring 90 per cent local content rules by the 1960s.

Fast-forward through the Whitlam era’s tentative liberalisation where tariffs were trimmed, but protection remained intact, and Hawke’s 1980s accords, where Labor’s tripartite pacts with the Business Council and ACTU funnelled billions into automotive research and development. The Coalition under Fraser paused the drift, but Hawke’s wage deals tied industry aid to productivity gains, a targeted, anticipatory policy straight from Labor’s playbook, with state ideology shaping labour and capital markets.

John Howard began phasing out Hawke’s tariffs to 5 per cent from 2002 out to 2010. But Howard also warned the industry that they had been given chances over and over again to become competitive off their own bat, and government support could not continue indefinitely.

Rudd’s election saw Labor reinstate anticipatory aid to the tune of $6.2 billion over 13 years for the ‘New Car Plan for a Greener Future’. Designed to encourage the industry to focus on low-emission vehicles, it was a complete failure.

Gillard axed the green car fund in 2011. But I don’t hear anybody crying about Gillard’s role in ending the industry.

Abbott’s 2013 Coalition axed it outright in 2014, citing liberal orthodoxy and, in my opinion, the smart option. Governments are inherently bad at picking winners, particularly Labor governments. Of course, the leftist narrative puts all the blame on Abbott, but the industry knew the public teat was drying up despite their best efforts to keep the subsidies flowing.

The end came swiftly. There were bipartisan fingerprints everywhere. As I argued in 2021, this wasn’t ideological purity but pragmatism wrestling policy inertia. Short-term governments inherit legacies that resist one-term overhauls, from the tariff entrenchment of the 1920s through to WTO compliance in the 1990s.

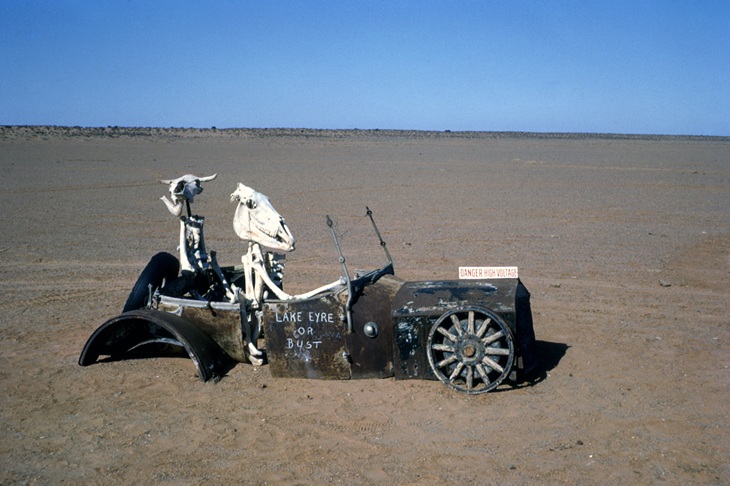

Hastie’s nostalgia resurrects car making as a ‘sovereign revival’. We exited the industry because of high costs in a small market amidst global competition. These haven’t vanished.

Yet history proves that we cannot ignore geopolitical realities.

Australia’s history proves that sovereign strength comes from pragmatic adaptation, not ideological purity. Economic liberalism posits that governments should not make what businesses can do more efficiently. The car manufacturing industry in Australia couldn’t make cars efficiently, so there is a role for government to play. In particular, when our national security is at stake.

Clearly, Hastie is on to something the ideologues can’t comprehend.

Dr Michael de Percy @FlaneurPolitiq is the Spectator Australia’s Canberra Press Gallery Correspondent. If you would like to support his writing, or read more of Michael, please visit his website.