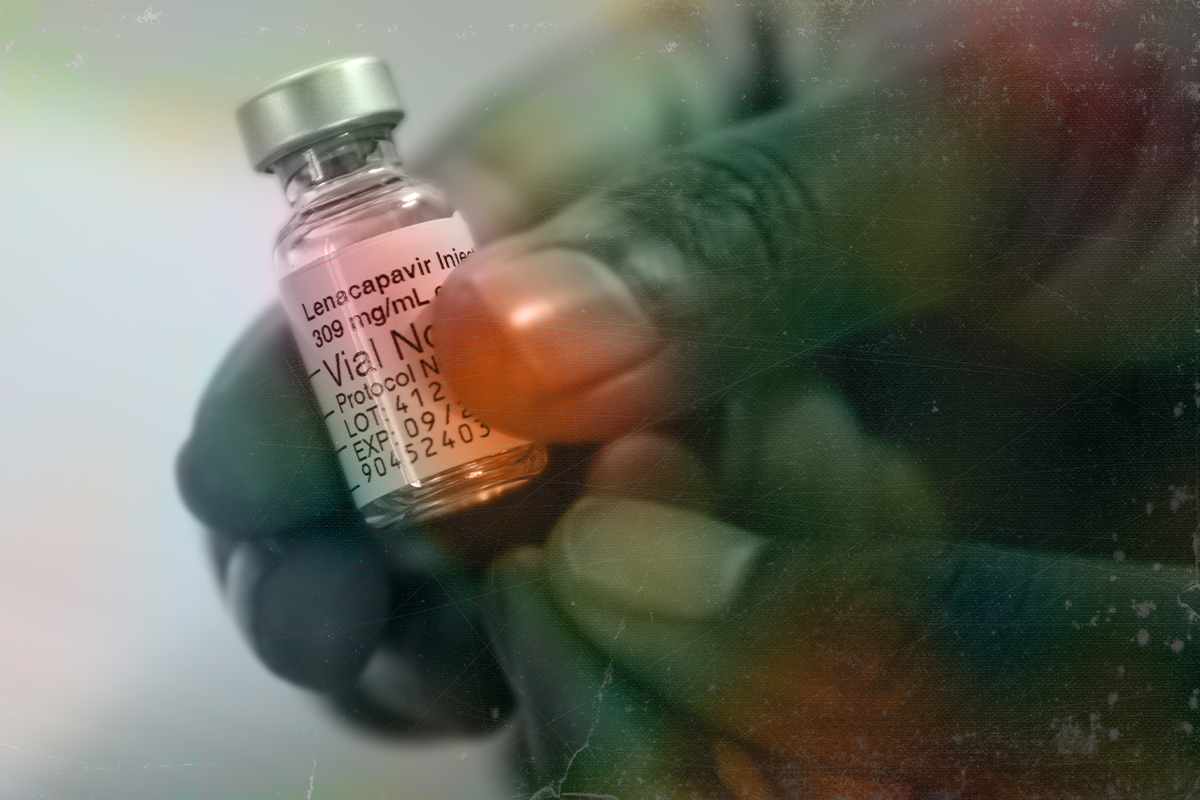

On Sept. 24, the California-based multinational corporation Gilead Sciences announced it would lower the price of lenacapavir — a highly effective pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) drug that prevents HIV transmission — from more than $28,000 per annual regimen to $40, starting in 2027. Winnie Byanyima, director of the United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, described Gilead’s price drop as a “watershed moment in the fight to end AIDS as a public health threat.”

But the new prices will not be applied universally. Gilead has signed six royalty-free voluntary license agreements that allow generic drug manufacturers to produce lenacapavir for use in 120 primarily low- and lower-middle-income countries, with production contracted to companies in India, Pakistan and Egypt. Twenty-six upper-middle-income countries, meanwhile, are excluded from Gilead’s license list, including most of Central and South America, countries across Eastern Europe, Asia and the Middle East, including Iran, Iraq and Palestine. According to 2023 data from UNAIDS, upper-middle-income countries account for roughly 41% of new HIV infections and 37% of the 40 million people living with HIV worldwide.

Medicine access and health groups are calling on Gilead to broaden its generic licensing to include all low- and middle-income countries.

“For the first time, we’re seeing a price that matches what independent studies estimate it actually costs to manufacture lenacapavir,” said K.M. Gopakumar, senior researcher at the Third World Network, an advocacy organization for sustainable and just development in the Global South. “But excluding some countries undermines the purpose of lenacapavir to prevent new infections. From a public health and ethical perspective, it doesn’t make sense.”

The new prices will not be applied universally.

Under the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, generics manufacturers are prohibited from exporting pharmaceutical ingredients or finished medicines to countries without licenses to produce those drugs. No exception is given for countries that issue compulsory licenses and bypass TRIPS rules within their own borders in the interest of public health.

Countries excluded from Gilead’s voluntary license agreements must therefore buy branded lenacapavir at the regular, higher price — or tell people living with HIV to wait until Gilead’s patents expire. This was supposed to begin in 2034, but Gilead is expected to use a practice known as patent evergreening — extending exclusivity based on minor modifications to the drug — to prolong its control of pricing in high- and middle-income countries through at least 2041, further delaying the arrival of affordable generics in the market.

The selective licensing creates “an artificial scarcity of affordable options,” said Chetali Rao, a biotechnologist and intellectual property lawyer with TWN, adding, “There are many manufacturers who can supply generics to these countries.” She called Gilead’s prohibitions “a very aggressive measure.”

Gilead’s licensing regime limits access to a groundbreaking treatment that requires only twice-annual injections. The company’s previous PrEP drug, the pill Truvada, in testing showed only up to 75% efficacy. Descovy pills have shown approximately 99% efficacy, but have not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for cis women. GlaxoSmithKlines’s cabotegravir, branded as Apretude and Vocabria, offers similar protection to lenacapavir, but it requires bimonthly injections. Another option, the dapivirine vaginal ring, needs monthly replacement and can leave people vulnerable to intimate partner violence. (A study on women’s agency in PrEP use in sub-Saharan Africa showed that when sexual activity is stigmatized, the discovery of a ring can prompt partners to remove and destroy it, and to inflict physical violence.)

Humanitarian experts see lenacapavir as a potential game changer for marginalized and criminalized communities, including LGBTQI+ people and sex workers. Médecins Sans Frontières reports that Gilead’s drug can be especially groundbreaking in humanitarian contexts “where flexibility and discretion are essential,” with fewer medical visits and less reliance on cold chain storage.

Last year, the number of people who died from AIDS was at its lowest point since the mid-1980s, and life expectancies of people living with HIV have increased over the decades. But experts fear an HIV/AIDS resurgence and a return to “the dark days of the epidemic.” Even within countries licensed to produce generic lenacapavir, dependency on philanthropic subsidies leaves the sustainability of drug production uncertain. Global prophylactic programs and clinics were decimated by the Trump administration’s dismantling of USAID programs that supported almost 90% of global PrEP programs. A report by Physicians for Human Rights details the scale of damage, leaving global programs to operate in “fragmented and precarious ways” and forcing patients to ration PrEP pills.

Gilead’s decision to forbid generic producers from exporting the drug to countries outside the license list has earned accusations that the company is contravening the spirit and letter of the 2001 Doha Declaration on TRIPS and public health. This critical amendment affirms countries’ rights to “access to medicines for all,” in line with Article 31 of the WTO’s intellectual property laws that protect countries’ sovereign right to override patents and issue compulsory licenses in the face of public health emergencies.

“Gilead’s greed will relegate communities around the world to inferior HIV prevention.”

The Health Justice Initiative and other public health advocacy organizations want to see lenacapavir included in the United Nations-backed Medicines Patent Pool, which makes generics production more accessible through nonexclusive public licensing and technology transfers. But the current policy of the United States and other major pharmaceutical producing nations aligns more closely with the private sector’s aggressive tactics that restrict access to lifesaving drugs. Countries are under mounting pressure from the United States to further reform intellectual property laws in favor of the private sector. Recent rulings in Brazil and Colombia to override private patents have drawn the predictable ire of the Office of the United States Trade Representative).

Gilead did not respond to Truthdig’s request for comment on the expansion of access to countries currently excluded from the voluntary license list, on the Medicines Patent Pool, and on the Doha Declaration.

Meanwhile, new treatments have brought the once-unimaginable into the realm of the possible. UNAIDS estimates that AIDS as an epidemic could be ended by 2030 — but only if governments prioritize public health over private profit.

“Gilead’s greed will relegate communities around the world to inferior HIV prevention,” said Asia Russell of Health GAP. “It will unnecessarily prolong this pandemic.”