Drawing Studio / CRAB Studio. Image © Richard Bryant

Drawing Studio / CRAB Studio. Image © Richard Bryant

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1034955/from-design-fiction-to-design-futures-the-changing-role-of-architecture-in-cultural-production

When Archigram published their fanatical vision for pneumatic cities and walking megastructures in the 1960s, they seemed to be designing buildings. Beneath the surface, the avant-gardeists were pushing culture through radical alternatives to lifestyles and forms of organizing in the city. Laboratories found themselves between the lines of copy on Domus or Casabella magazines, propositions doubling as blueprints for the civilizations to come. From Gropius’s Bauhaus in 1919 to Arcosanti’s desert experiments in the 1970s, architecture operated as a form of cultural prophecy. Built form was the argument. The drawing was the vision. Today, we live in a world that remarkably resembles what the starchitects of the 1900s imagined – modular construction, interconnected digital cities, and automated systems. Yet contemporary architecture rarely proposes culture with the same totalizing confidence.

Roughly between the 1920s and 1970s, architectural manifestos functioned as performative documents that declared new possibilities for public life. A conjunction of forces made the shaping of culture through architecture inevitable. Architecture still operated within a coherent canon, speaking to a relatively small audience of professionals, critics, and state patrons who shared certain assumptions about progress and modernity. Print media circulated quickly and cheaply across schools and ateliers, allowing ideas to spread rapidly through this concentrated community. Architects belonging to this time saw themselves as cultural vanguards remaking society in response to industrialization and the evolving dynamics of political power.

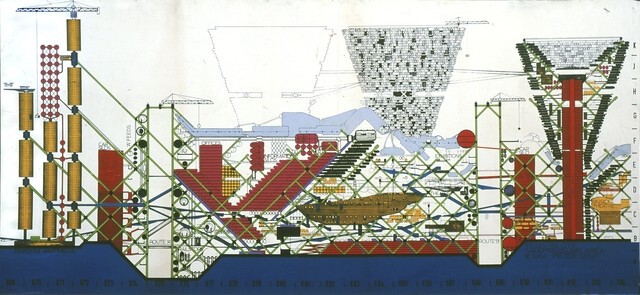

The Plug-In City / Peter Cook, Archigram. Image via Archigram Archives

The Plug-In City / Peter Cook, Archigram. Image via Archigram Archives

Institutions rewarded these programmatic visions. Governments and municipal authorities, particularly in postwar reconstruction efforts, were receptive to grand, top-down plans. Brasília, Chandigarh, and the British New Towns attempted to conjure new social orders through spatial organization. A structure could embody an entire philosophy of living.

Related Article The Project as Argument: What is Architectural Thinking?

The radical collectives and publications of this era, such as Futurism and Metabolism, functioned as conduits of cultural dissemination. Arcosanti stands as a great example of this impulse. The project was an experiment where the built form itself lays the framework for an alternative culture, where architecture doesn’t respond to society but attempts to create it.

The conditions that enabled manifesto-driven culture-making have dissolved. Power and agency are now fragmented. The early and mid-20th century had strong nation-state or corporate patrons who commissioned “new worlds.” Today, governance operates through complex public-private partnerships, and large projects emerge from negotiations among dozens of stakeholders. There’s rarely a single visionary with the mandate to remake culture at a city scale.

Aguahoja / Neri Oxman + MIT. Image Courtesy of MIT Media Lab

Aguahoja / Neri Oxman + MIT. Image Courtesy of MIT Media Lab

Neoliberal economics has made capital risk averse. Large speculative visions don’t get built because investment demands predictable returns. The experimental utopias that once found patrons in ambitious municipalities have migrated into smaller interventions or exist purely as speculative media projects. Meanwhile, culture itself has shifted from hardware to software. Social networks and digital platforms now produce culture as much as built form does.

Contemporary architectural discourse feels critical, data-driven, policy-oriented. The crisis mindset around climate change, housing, and migration pushes conversation toward codes, retrofits, regulations – pragmatic frameworks rather than utopian imagery. What is the contemporary architect’s role in cultural production now that the future has become a conversation rather than a declaration?

Culture as Process

To claim that architecture no longer produces culture would be wrong – the mode has simply changed. Contemporary architects engage people in design processes in different ways and at different scales of future-making, with improvising, learning, becoming, and living as themes able to accommodate uncertain and changing situations. Culture-making has become distributed, emerging from networks of smaller interventions rather than singular heroic objects.

Studio Gang’s Arcus Center for Social Justice Leadership doesn’t propose a utopian community so much as create infrastructure for civic dialogue and collective action. The culture it produces is procedural – architecture as a framework for ongoing social negotiation. Tatiana Bilbao’s Sustainable Housing Prototype embodies culture as something co-produced with local communities, adaptable and affordable.

Arcus Center for Social Justice Leadership / Studio Gang. Image © Steve Hall for Hedrich Blessing

Arcus Center for Social Justice Leadership / Studio Gang. Image © Steve Hall for Hedrich Blessing

Tactical urbanism presents a citizen-led approach to neighborhood building using short-term, scalable interventions to catalyze long-term change. The method inverts the manifesto logic. Rather than declaring a future and building toward it, tactical approaches test possibilities, gather feedback, and iterate. The process itself becomes the cultural production.

Even practices working with cutting-edge technology like Neri Oxman’s practice operate differently than their modernist predecessors. Her material ecology and bio-design work imagines cultures where materials, biology, and built form co-evolve. The emergent systems incorporate feedback and adaptation from the start.

Social Housing Prototype, 2015. Image © Tatiana BilbaoDesign Fiction to Design Futures

Social Housing Prototype, 2015. Image © Tatiana BilbaoDesign Fiction to Design Futures

This shift from “design fiction” to “design futures” influences architecture’s relationship to cultural production. Design Fiction operated through speculative narratives where architects imagined a future and rendered it compellingly enough to shift public perception. The power lay in the clarity and boldness of the vision.

Design Futures operates as collaborative foresight, exploring multiple plausible scenarios rather than declaring a single preferred one. It is participatory by necessity, acknowledging that in an era of democratized media and distributed agency, no single voice can claim to speak for culture. The architect’s role shifts from oracle to facilitator.What is the architect’s role when everyone can imagine the future?

Plaza de bolsillo en Santiago de Chile. Image © Plataforma Urbana

Plaza de bolsillo en Santiago de Chile. Image © Plataforma Urbana

In the manifesto era, specialized training and institutional position granted architects authority to declare how cities might support evolving lifestyles. Today, communities organize their own design charrettes. Developers use algorithms to optimize spatial programs. Social media platforms generate more cultural momentum than any built project. Perhaps architecture’s contribution to cultural production now lies not in proposing grand visions but in creating frameworks for collective imagination.

The age of the manifesto was an era of grand conviction when architects believed they could redraw the world and felt permitted, even obliged, to do so. Out of that confidence came works of astonishing scale and imagination: the Metabolists’ megastructures, Constant’s New Babylon, Superstudio’s Continuous Monument. By contrast, today’s plural and participatory architectural culture rarely aspires to such totalizing visions. The demands of iteration shape a different kind of creativity, constructing the frameworks through which futures might emerge. The mid-century avant-garde sought to bend perception through the sheer intensity of vision, while today’s designers offer platforms that invite collective orientation. Both are forms of cultural production. Both shape how we inhabit the world.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: The Architecture of Culture Today. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.