There’s a high-pitched sound that once echoed across an Australian tropical island that will never be heard again. As the Christmas Island shrew (Crocidura trichura) began to decline in numbers, first after the accidental introduction of rats, which spread disease, then from the introduction of an invasive snake, no one thought to record it.

Now the tiny creature has been declared extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which manages the authoritative Red List of threatened species. The shrew had not been sighted since 1984, and there had only been four reported over the last 120 years, meaning hope of finding one again had been fading.

The official announcement was made in Abu Dhabi at the IUCN’s annual conference. Five other species from around the world were also declared extinct, including the slender-billed curlew and a cone snail.

The Christmas Island sound that survived

Charles Darwin University Professor of Conservation Biology, John Woinarski, told Yahoo News Australia that he doesn’t blame anyone for not recording the shrew, “but we could have done better”.

“We know about the shrew largely from very limited observations in the 1890s, when the island was first surveyed and settled. The reports from those early naturalists were that it was highly vocal and made a continuous high-pitched bat-like squeak over the nighttime,” he said.

“One of the most mysterious and strange features of its extinction is so little is known about this vertebrate species. It’s remarkable.”

There are recordings of the calls of the last-known Christmas Island pipistrelle (Pipistrellus murrayi), a bat that went extinct around the same time as the shrew. The National Film and Sound Archive has a recording in its collection here.

“It’s a really powerful message. You can listen to that last bat calling and imagine what it was thinking at the time, and what we’ve missed out on that’s been lost.”

Related: 🎥 Rare colour footage of extinct Australian animal seen again

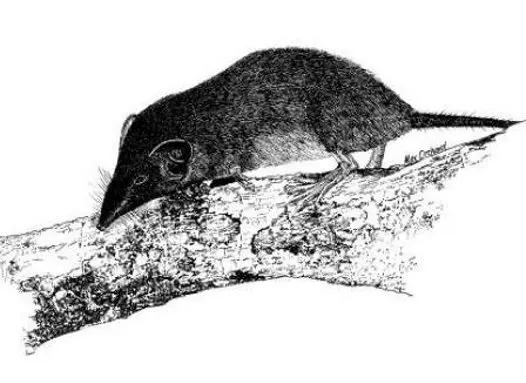

A sketch of a Christmas Island shrew. Source: Max Orchard via Australian Museum

Other sounds vanishing from parts of AustraliaHaunting feeling on Christmas Island

Professor Woinarski is a director of the IUCN Australasian Marsupials and Monotremes Specialist Species Group, a member of the independent expert group, the Biodiversity Council, and a director of the Australian Wildlife Conservancy.

Today, when he visits Christmas Island, he treasures it as an important refuge for species that can no longer survive on the mainland due to habitat destruction and invasive predators. But he’s also haunted by a “demoralising sense of what has been lost” since settlement on the island.

He notes many of the ethnic Malays who lost relatives who worked on the island in terrible, low-paying conditions refer to it as a “land of ghosts”. “It’s the same with much of the biodiversity as well, that there are ghosts in the landscape of the animal species that became extinct there,” he said.

Today Christmas Island remains an important refuge for wildlife, despite the extinctions of several species. Source: Getty

Government responds to IUCN announcement

Three other Australian mammals, which haven’t been seen in generations, the marl (Perameles myosuros), the south-eastern striped bandicoot (Perameles notina), and the Nullabor barred bandicoot (Perameles papillon), were also assessed for the first time and entered on the Red List as extinct.

Responding to the IUCN’s decision to list the shrew as extinct, the Department of Environment (DCCEEW) said the “loss of any species is a tragedy”.

“The Australian Government drew a line in the sand on this in 2022 by committing to prevent new extinctions in the Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032,” a spokesperson told Yahoo.

The shrew remains listed as critically endangered on the list of threatened species protected under the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. It confirmed it has yet to receive the required nomination to consider listing it as extinct.

Another Australian species declared extinct by the IUCN but not the EPBC is the mountain mist frog, which was last seen in the 1990s, and was wiped out due to chytrid fungus.

Environment Minister Murray Watt was contacted for comment.

Hope as Australia works to fix ‘weak’ nature protection laws

Having lost 39 mammalian species since European settlement, Australia has the worst record on Earth.

During an independent review five years ago, Australia’s current nature protection laws were described as “ineffective”, “weak” and “tokenistic”. As the government continues to consult with business and environment groups about how to fix them, Professor Woinarski hopes the talk of the shrew will be remembered.

“It’d be lovely to think that poor, innocent, sort of almost nondescript, shrew would have an impact. I suspect it won’t, but it would be great if it did” he said.

“Preventing extinction should be a cornerstone of changes in national environmental legislation.”

Love Australia’s weird and wonderful environment? 🐊🦘😳 Get our new newsletter showcasing the week’s best stories.