Rinshunkaku restoration, 2019-2022. Documented in “Artisans of Reiwa – The Restoration of Rinshunkaku”. Image © Katsumasa Tanaka

Rinshunkaku restoration, 2019-2022. Documented in “Artisans of Reiwa – The Restoration of Rinshunkaku”. Image © Katsumasa Tanaka

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1034690/architecture-as-soft-power-cultural-diplomacy-and-its-role-in-shaping-architectural-production

Cultural diplomacy refers to the use of cultural expression and creative exchange to foster understanding and build relationships between nations. In this context, architecture has long played a distinctive role. Beyond its functional and aesthetic dimensions, it serves as a medium of communication, a language through which countries express identity, values, and ambition on the global stage.

Architecture operates as a form of soft power — persuasive rather than coercive — enabling nations to project influence through material presence. From modernist embassies in the post-war era to monumental pavilions at world expositions, governments and institutions have recognized the built environment’s potential to shape perception. By commissioning prominent architects and adopting specific design languages, countries have used architecture to signal modernity, tradition, innovation, or stability.

In the 21st century, global connectivity and geopolitical fragmentation have transformed the scope of architectural cultural diplomacy. While established powers continue to use high-profile projects to reaffirm influence, emerging economies, smaller nations, and even cities are leveraging architecture to claim cultural agency. This expansion has diversified the narratives and aesthetics at play — but it has also exposed tensions between representation, authenticity, and inclusivity, particularly when projects serve symbolic agendas more than the communities they are built for.

Related Article Concéntrico 2025: The Politics of Urban Presence Buildings as Ambassadors

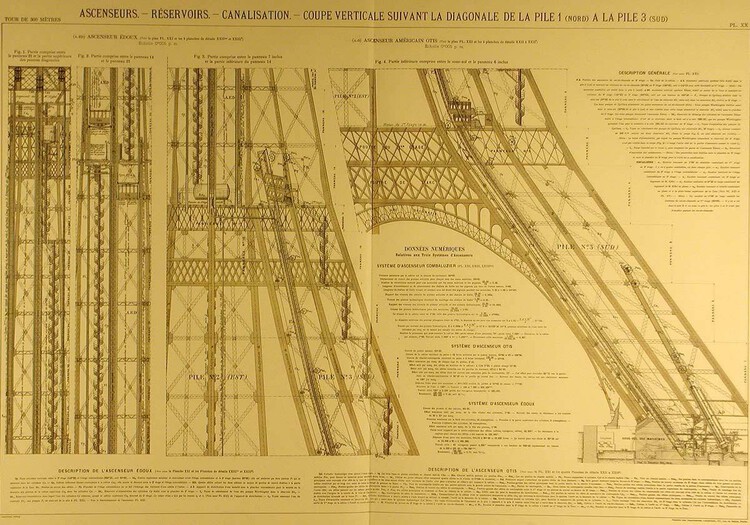

Long before the term “cultural diplomacy” was coined, architecture was already performing its role as a silent envoy. States and institutions understood that buildings could speak on their behalf — projecting identity, signalling alliances, and shaping perceptions in ways that words alone could not. In the 19th century, this awareness took center stage at the great international expositions, where architecture became a stage for industrial, artistic, and political display. The Great Exhibition in London unfolded beneath Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, a vast structure of glass and iron that not only showcased Britain’s engineering prowess but also embodied its imperial confidence. Just a few decades later, the Exposition Universelle in Paris crowned the city with the Eiffel Tower, a radical gesture in iron that proclaimed France’s modernity and ambition to lead in technology and culture.

Eiffel Tower / Gustave Eiffel. Image

Eiffel Tower / Gustave Eiffel. Image

These events established the national pavilion as a strategic instrument of soft power. Architecture was no longer a neutral container for exhibits; it was itself an exhibit, carefully designed to narrate a nation’s story. The German Pavilion at the Barcelona International Exposition, by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, distilled Germany’s desired image into a precise composition of marble, glass, and onyx — signalling refinement, order, and a progressive break from the past. A decade later, Alvar Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion for the New York World’s Fair wove modernist principles with tactile materials and vernacular references, presenting Finland as both forward-looking and grounded in tradition.

Barcelona Pavilion / Mies van der Rohe . Image © Gili Merin

Barcelona Pavilion / Mies van der Rohe . Image © Gili Merin

During the Cold War, this architectural theatre became overtly ideological. The USSR‘s pavilions at international expos — monumental, richly ornamented, and filled with symbols of collective strength — projected socialism’s values and industrial might. In contrast, the United States adopted lighter, more transparent designs, turning modern architecture into a diplomatic language of democracy and openness. These contrasting architectural languages were part of a larger geopolitical dialogue, one that used design to communicate ideological alignment and national identity. The strategies varied, but the intention was the same: to shape perception through form.

Beyond the superpowers, other nations also recognized the potential of architecture to reposition themselves on the global stage. Brazil’s pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, designed by Lucio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer, introduced the sinuous modernism that would later define Brasília, signalling cultural vitality and economic optimism. Japan’s Pavilion at Expo ’70 in Osaka, by Kenzō Tange, combined advanced engineering with spatial ideas drawn from traditional Japanese architecture, presenting the country as a society able to reconcile innovation with heritage.

Across all these examples, economic capacity played a decisive role. For some nations, such events offered a relatively low-cost yet high-profile opportunity to shape their image; for others, they became exercises in national branding, driven by substantial investment and spectacle. Architecture thus became a measure of how nations negotiate identity, ambition, and economic reality, revealing as much about their cultural values as about the resources they can mobilise to express them.

But seen together, these examples reveal a continuity of intent: each building was conceived as more than a venue for events or diplomatic functions. They were instruments of statecraft, translating political ambition into spatial form. Through the choice of materials, the orchestration of space, and the symbolism embedded in architectural detail, these structures acted as ambassadors in their own right — shaping international narratives long after the exhibitions closed and the delegations returned home.

Exposition Internationale des Arts De╠ücoratifs et Industriels Modernes / Various Architects. Image Courtesy of Wikimedia user François GOGLINS (Public Domain)Institutions, Networks, and Architectural Presence

Exposition Internationale des Arts De╠ücoratifs et Industriels Modernes / Various Architects. Image Courtesy of Wikimedia user François GOGLINS (Public Domain)Institutions, Networks, and Architectural Presence

Following World War II, the United States promoted a vision of openness through a series of modernist embassies, such as Eero Saarinen’s U.S. Embassy in London, whose glass façades and open plans sought to contrast with the closed monumentalism of Soviet state architecture. These buildings translated political ideals into spatial form, presenting modernism as a diplomatic language of transparency and democracy.

U.S. Embassy in London / Eero Saarinen . Image © Wikiedia, uner Public Domain license

U.S. Embassy in London / Eero Saarinen . Image © Wikiedia, uner Public Domain license

Since the early twentieth century, nations have formalized these cultural outposts. The networks of cultural institutions that emerged provided a slower, more sustained form of architectural diplomacy. These buildings — embassies, cultural centres, libraries, and institutes — were conceived as venues for teaching languages or hosting exhibitions, as physical representations of national identity embedded in the urban fabric of another country. They embodied the idea that architecture could hold a permanent diplomatic position, quietly yet consistently broadcasting values, aesthetics, and political intent. One of the greatest examples of this is The British Council, established in 1934, which rolled out a network of cultural centres whose architecture often mirrored Britain’s evolving self-image. Post-war buildings embraced modernist clarity, projecting accessibility, openness, and a break from colonial associations, while later renovations sometimes incorporated local architectural motifs to signal mutual respect. The Goethe-Institut, founded in 1951, took a similarly deliberate approach: whether in Tokyo, São Paulo, or Lagos, its spaces balance contemporary German design principles with an adaptability that allows them to integrate into vastly different cultural contexts.

Goethe Institute / Kéré Architecture. Image Courtesy of Kéré Architecture

Goethe Institute / Kéré Architecture. Image Courtesy of Kéré Architecture

In Asia, the Japan Foundation’s overseas centres often reinterpret traditional Japanese spatial ideas — such as modularity, natural light, and the integration of gardens — within modern construction methods. These design choices subtly frame Japanese culture as both rooted in tradition and oriented toward innovation. In a simillar way, the Alliance Française, tends to adapt to existing urban buildings, yet relies on signage, layout, and cultural programming to maintain a recognizable identity. This demonstrates that architectural diplomacy can also work through consistency in smaller design gestures, especially when resources are limited.

International organisations have also leveraged architecture for cultural diplomacy. UNESCO’s built presence — from its Paris headquarters designed by Marcel Breuer, Pier Luigi Nervi, and Bernard Zehrfuss to its field offices around the world — is deliberately modern and collaborative, a visual metaphor for its mission to foster peace through education, science, and culture. Beyond its own buildings, UNESCO’s influence extends to heritage restoration projects such as the rebuilding of the Old Bridge in Mostar after the Bosnian war or the conservation of Timbuktu’s ancient manuscripts, both of which carry symbolic weight far beyond their physical boundaries and affirm participating nations’ commitment to cultural continuity and post-conflict reconciliation.

UNESCO Headquarters . Image © Fred Romero via Flickr under CC BY 2.0

UNESCO Headquarters . Image © Fred Romero via Flickr under CC BY 2.0

Over the past few decades, architectural diplomacy has expanded well beyond Europe and North America. Nations in Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and Southeast Asia are commissioning landmark cultural buildings to reposition themselves in global networks, introducing new aesthetic languages and reshaping the geography of influence. In the Middle East, Qatar’s Museum of Islamic Art, designed by I.M. Pei, and the National Museum of Qatar, designed by Ateliers Jean Nouvel, utilize striking architecture to reinforce the country’s position as a cultural hub, connecting contemporary ambition with its historical legacy.

National Museum of Qatar / Ateliers Jean Nouvel. Image Courtesy of Atelier Jean Nouvel

National Museum of Qatar / Ateliers Jean Nouvel. Image Courtesy of Atelier Jean Nouvel

Economic resources inevitably shape these initiatives. Gulf nations, benefiting from significant oil and gas revenues, have the means to commission buildings from internationally renowned architects and create entire cultural districts, as in Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island. In contrast, many smaller or less wealthy nations turn to adaptive reuse, community-led construction, or strategic partnerships with international organisations. The Chilean Pavilion at the 2016 Venice Biennale, built with simple timber framing and designed to be disassembled and reused, exemplifies how a compelling architectural statement can be made with modest means, aligning economic pragmatism with a message of sustainability and resilience.

Chile’s Pavilion at the 2016 Venice Biennale. Image Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Chile’s Pavilion at the 2016 Venice Biennale. Image Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

In Latin America, projects such as the España Library Park by Giancarlo Mazzanti blur the line between cultural and social infrastructure, projecting an image of regeneration rooted in education and public space. Similarly, Singapore’s National Gallery transforms colonial-era buildings into a contemporary museum, presenting the city as a bridge between past and future while aligning with global values of sustainability and reuse.

Spain Library / Giancarlo Mazzanti. Image

Spain Library / Giancarlo Mazzanti. Image

Whether monumental or modest, these projects reveal how architecture measures cultural ambition against economic reality. Their buildings age, adapt, and respond to the political climates of their host cities: an embassy might replace façade materials to meet new security standards; a cultural centre might expand to accommodate digital programming; a library might redesign its spaces to reflect evolving ideas of accessibility. When designed to evolve and engage, they become genuine spaces of exchange — tangible markers of presence that communicate through both form and purpose.

Critical Perspectives: Representation, Access, and Inequality

As architecture became a key instrument of cultural diplomacy, its ability to shape perception also exposed deeper contradictions. The same buildings that project ideals of openness and exchange can, in practice, reproduce social and economic divisions. National representation often reflects political ambition more than public need, turning culture into a curated image rather than a shared experience.

National Museum of Qatar / Ateliers Jean Nouvel. Image Courtesy of Atelier Jean Nouvel

National Museum of Qatar / Ateliers Jean Nouvel. Image Courtesy of Atelier Jean Nouvel

Yet the expansion of architectural cultural diplomacy into new geographies is not without contradictions. In many cases, these projects are conceived within political and economic frameworks that prioritise global visibility over local accessibility. The commissioning of “star architects” can overshadow local design talent, while high-profile cultural districts often emerge in parallel with processes of urban speculation and gentrification. The result is that the spaces designed to symbolise openness and exchange may, in practice, be inaccessible to large segments of the population they are meant to represent. Such approaches point toward a different future for architectural cultural diplomacy, one in which buildings are not only ambassadors but also active participants in the life of their communities, both local and global. This requires rethinking the metrics of success: moving away from visitor counts and media coverage toward measures of inclusivity, adaptability, and long-term relevance. The architectural value of these projects lies not just in their ability to project identity outward, but in their capacity to embed themselves meaningfully in the places and relationships they inhabit.

Wahyu Pratomo and Kris Provoost. Image

Wahyu Pratomo and Kris Provoost. Image

Economic capacity is therefore not only a driver of what gets built, but also a filter that determines who gets to speak in the global conversation. Countries with limited resources face structural disadvantages in producing architecture that can compete in the spectacular arenas, leading to an uneven cultural map where some narratives are amplified while others remain marginal. This raises a fundamental question about the nature of representation in architectural cultural diplomacy: whose story is being told, and to whom? In pursuing an image that appeals to international audiences, governments and institutions risk presenting a singular, polished version of national identity that ignores internal diversity or conflict. By doing so, architecture becomes a tool not just for cultural promotion, but for political narrative management; a selective mirror that reflects only the aspects a nation wishes to project.

© Wikiedia, uner Public Domain license

© Wikiedia, uner Public Domain license

Many of the winners of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, for example, demonstrate how architectural diplomacy can emerge from modest means, combining craftsmanship, local knowledge, and social engagement rather than star power. Similarly, the network of public libraries developed in Latin American cities such as Medellín or Bogotá has positioned architecture as a tool of inclusion and regeneration — a quieter yet profoundly diplomatic form of representation. Whether monumental or modest, these projects share a common challenge: striking a balance between symbolic representation and social relevance. Permanent institutions can easily become static symbols — celebrated abroad but disconnected from their local context. Yet when designed with openness and adaptability, they can operate as genuine spaces of exchange, embodying the diplomatic ideals they were meant to project.

Both temporary and permanent forms of architectural diplomacy are caught in this paradox. Expos, biennials, and global events risk prioritizing spectacle over substance, transforming architecture into a fleeting performance designed for attention rather than legacy. For architects working in these contexts, the challenge lies in negotiating between symbolic ambition and social responsibility. The most effective projects are those that manage to speak to both the global stage and the local street, ensuring that the spaces created for diplomatic purposes also serve as inclusive, democratic environments for everyday life. Without this balance, the architecture of cultural diplomacy risks becoming an empty emblem, a stage set whose audience is everywhere except at home.

Ultimately, the most meaningful contributions will be those that move beyond image-making to foster genuine cultural exchange, social inclusion, and shared authorship. For architects and institutions alike, the challenge is to align the symbolic power of architecture with the democratic potential of public space. In doing so, cultural diplomacy can evolve from a carefully managed performance into a shared platform for mutual understanding and equitable participation in shaping the built environment.

Barcelona Pavilion / Mies van der Rohe . Image © Flickr – vladimix. Used under Creative Commons

Barcelona Pavilion / Mies van der Rohe . Image © Flickr – vladimix. Used under Creative Commons

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: The Architecture of Culture Today. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

Related Article Concéntrico 2025: The Politics of Urban Presence

New York Pavillion 1939 /Lucio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer. Image Courtesy of Carlos Eduardo Comas, via revista ArqTexto n.16

New York Pavillion 1939 /Lucio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer. Image Courtesy of Carlos Eduardo Comas, via revista ArqTexto n.16 Rinshunkaku restoration, 2019-2022. Documented in “Artisans of Reiwa – The Restoration of Rinshunkaku”. Image © Katsumasa Tanaka

Rinshunkaku restoration, 2019-2022. Documented in “Artisans of Reiwa – The Restoration of Rinshunkaku”. Image © Katsumasa Tanaka Rinshunkaku restoration, 2019-2022. Documented in “Artisans of Reiwa – The Restoration of Rinshunkaku”. Image © Katsumasa Tanaka

Rinshunkaku restoration, 2019-2022. Documented in “Artisans of Reiwa – The Restoration of Rinshunkaku”. Image © Katsumasa Tanaka