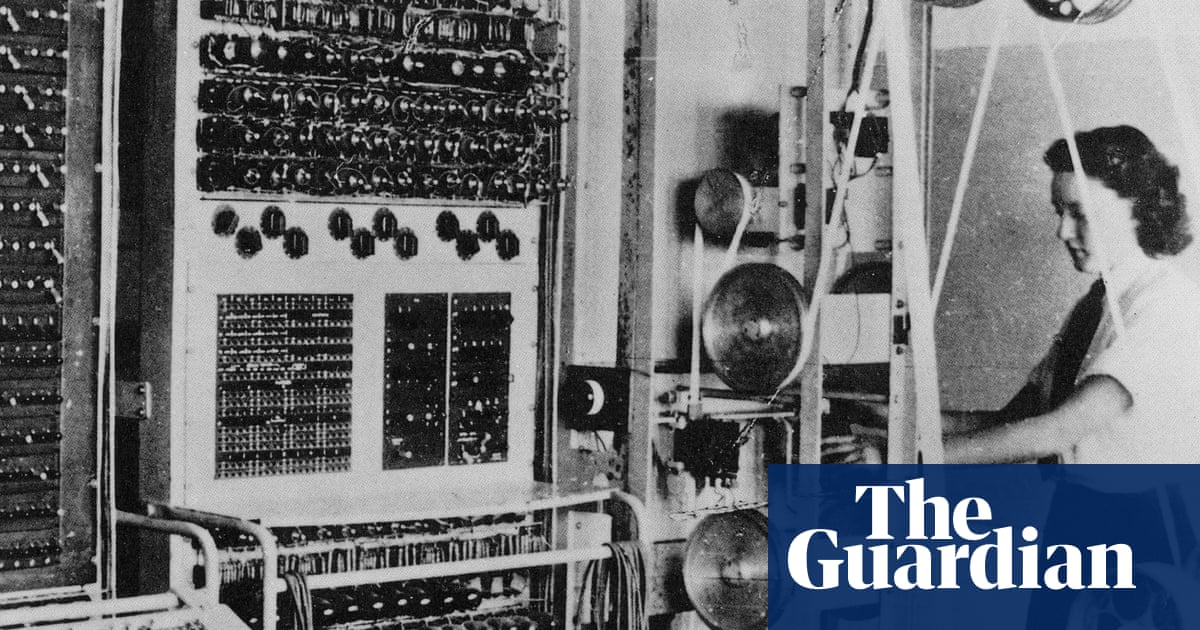

Andrew Smith is right to applaud the work of Tommy Flowers for building Colossus, the world’s first digital programmable computer, delivered to Bletchley Park in 1944 (Move over, Alan Turing: meet the working-class hero of Bletchley Park you didn’t see in the movies, 12 October). The piece concludes with Flowers stressing: “It’s never just one person in one place” – teamwork and collaboration are key. This is even truer than the article might imply, when it says “subsequent models” of Colossus “included many new features and innovations”, as if these had been the result of Flowers working alone, just upgrading his design. Quite the contrary.

It is well documented (for example, in the 2006 book Colossus by B Jack Copeland and others) that the Bletchley Park codebreakers Jack Good and Donald Michie not only utilised Colossus to help break the codes, they enhanced the computer; it was these developments that were so successfully incorporated by Flowers in subsequent machines.

This was teamwork between Flowers the engineer and the codebreakers, who came from a range of disciplines, from mathematics to the humanities. Hence the need to teach a whole range of subject areas, rather than what might appear the most useful.

But this goes far beyond the importance of teamwork. It’s a dramatic demonstration that it’s quite wrong to think that a new machine X will increase output by Y. The actual impact will depend on those working on the new machine. Hence the need to go beyond just training for today’s skills. We need people with the capabilities to work with new technologies they have not come across, let alone been “skilled” for, and the motivation to put those capabilities to good effect. For this, we need broad-based, lifelong learning as a permanent national necessity.

Prof Jonathan Michie

University of Oxford

Have an opinion on anything you’ve read in the Guardian today? Please email us your letter and it will be considered for publication in our letters section.