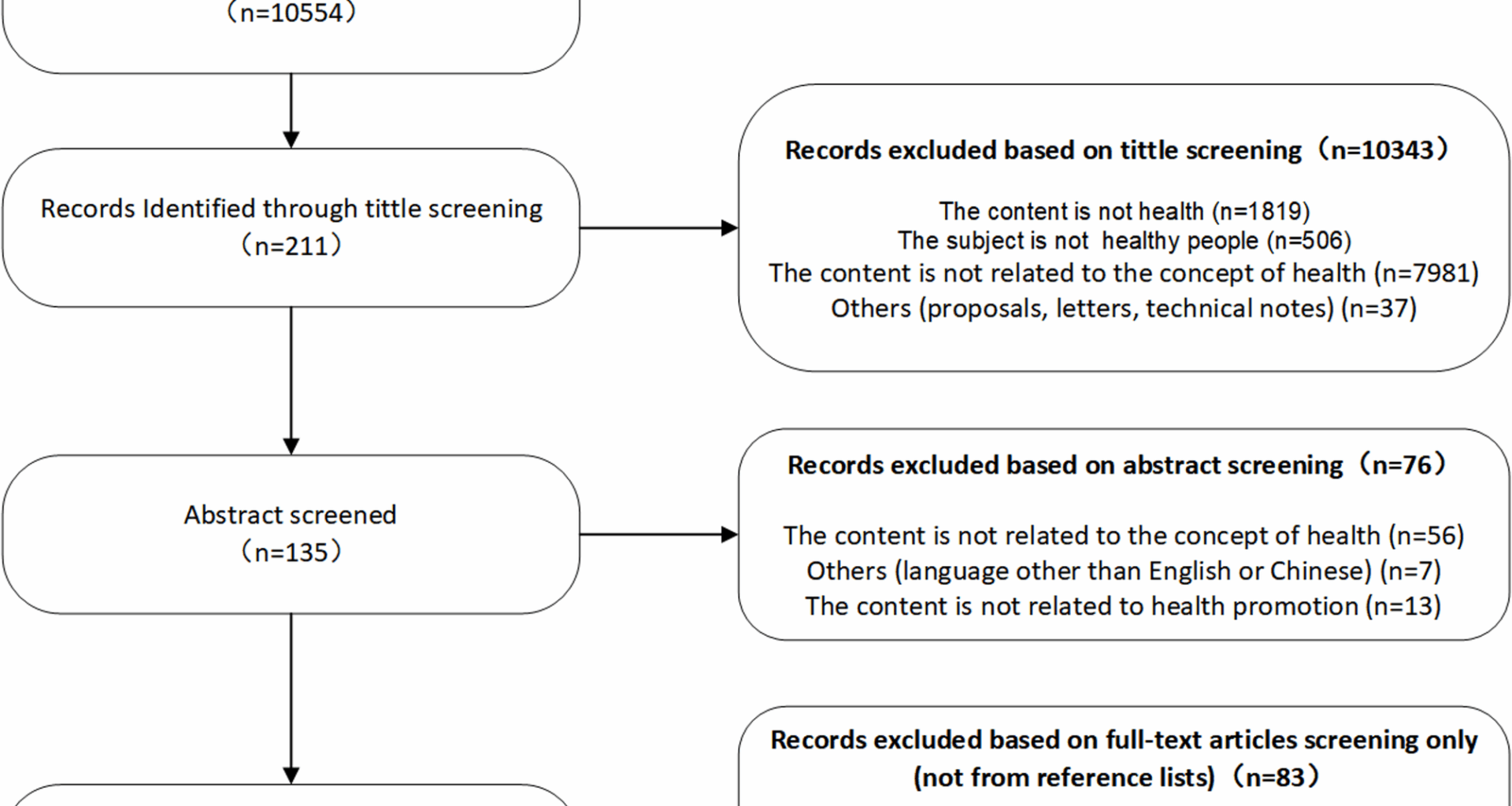

Evolution of the concept of health

Since the seminal declaration by the WHO in 1948, the foundation of the health definition has been established on a tripartite framework encompassing physical, mental, and social well-being [8]. However, there exists a disconnect between these abstractions and their practical application, which even causes people to feel uneasy about health: “In order to be healthy, I can’t have any illness or weakness, and I also need to be happy, so health is unattainable for me?“ [15]. While the WHO’ s definition sets forth universal aspirations for health, it falls short in providing a roadmap for the achieving these goals [16]. To align with evolving societal needs, the concept of health must be adapted to address new challenges and contexts. Scholars across historical and academic contexts have enriched this complex concept with diverse connotations, primarily in the following areas:

Health as a balance/stasis

In the late 19th to early 20th centuries, the concept of physiological equilibrium emerged. This opinion originated from Claude Bernard’s physiological research and was conceptualized in Walter Cannon’s theory of homeostasis, stating that health is internal balance and stability of bodily states [17]. Aaron Antonovsky likewise denied the assumption that stability is biology’ s gold stand, ardarguing the human organism exists prototypically in “heterostatic disequilibrium” — rejecting stability as the biological norm and reframing health as active adaptation within inherent imbalance [18]. Dussault et al. emphasized the self-regulatory capacity to restore function amid challenges [19]; Sartorius broadened equilibrium to include internal and social harmony [20]; the Meikirch Model conceptualized health as emerging from positive, dynamic interactions between individual potential, demands, and environment [21]; recent discourse explicitly positions health as the dynamic equilibrium of physical, mental, social, and existential well-being, achieved through adaptation to life’s demands and environmental conditions [22]. Collectively, these perspectives converge in their consideration of health as a balance between internal stability and external perturbations, emphasizing a state of “balance” over the unilateral integrity of functionalities.

Health as a dynamic resilience

Antonovsky coined the term “salutogenesis,” which means “the origins of health,” and correspondingly provided an answer to the question: “The origins of health lie in a sense of coherence.” This perspective laid crucial groundwork for viewing health as a dynamic resilience [23]. Critiques of the WHO’ s 1948 definition further catalyzed this paradigm shift. This broad scope of health was deemed impractical, as it renders health outcomes difficult to measure [24]. In response, an international health experts panel criticized the WHO definition of health, stating that it contributed to the medicalization of society and was insufficient for addressing chronic diseases, neither operational nor measurable [25]. This reframing emphasizes the capacity to cope and proposes that the definition of health should encompass “the ability to cope with, maintain, and restore one’s integrity, sense of balance, and well-being,” which is defined as “the ability to adapt and manage oneself.” resonating with the concept of resilience [26, 27]. Several researchers further aligned adaptation with the concept of resilience [28]. Compared to a static definition of health, resilience more attention should be paid to individuals’ ability to cope with, maintain, and recover when facing challenges. Therefore, we should reconsider the definition of health as a dynamic, adaptive process of resilience rather than just a static, idealized fixed state. This concept of health helps us better address the health challenges of the modern world and achieve individual and societal well-being [29].

Health as a continuum: disease and health can coexist

Antonovsky proposed health-disease not as a dichotomy but as a dynamic continuum, shifting focus from pathogenesis (“causes of disease”) to salutogenesis (“origins of health”) [23, 30]. This paradigm reframes the core question: how is health achieved despite pathology? Subsequently, Boorse [31] argued that labeling individuals as “unhealthy” is inaccurate when a disease does not substantially increase injury or death risk, worsen health outcomes, or impair physiological function. It establishes the compatibility of health and disease. Considering population aging and changes in the disease spectrum, more scholars believe that health is not the complete opposite of disease [32, 33]. Health and poor health are not dichotomous but rather two parts on a continuum. The absence of disease or disability does not equate to good health [34, 35]. A contemporary health definition transcends prior paradigms by acknowledging that perfection is unattainable to varying degrees. This definition suggests that chronic disease management exemplifies health not as eradication of pathology, but as sustained equilibrium within constraints. This continuum model prioritizes holistic quality of life over disease presence or absence, centering on the individual’s capacity for resilient adaptation amid life stressors.

Expanding the scope of health to environmental health

Environmental health relates to all aspects of human health, spanning natural and anthropogenic environments. As ecological degradation accelerates, public focus on environmental health has grown significantly. The definition of health should also be expanded to encompass environmental health to reflect human responsibility for the ecological environment. The Lancet editorial suggests that the conceptual framework of health should further expand to include social and environmental health. The WHO proposed the concept of “One Health“(2011), operationalized this holism as “a comprehensive, integrated approach to sustainably balance and optimize health across humans, animals, and ecosystems“ [36] Building upon this, Concord proposed a new definition of human health, suggesting that the definition of health should expand to include a fourth dimension—environmental health [33]. Incorporating environmental health into the health concept encourages individuals to assess health from a broader perspective, fostering harmony between humanity and nature, individuals and communities, and people and society.

The antecedents of health

Prerequisites refer to events or situations that preexist before the concept is formed. Based on the summary of the literature, the preconditions and influential factors of health can be summarized as follows:

Medical model

As our exploration of life’ s essence deepens and medical knowledge advances, conceptualizations of health have evolved over time. The concept of health has evolved from early ambiguity to modern clarity, and now to diversity and re-ambiguity. Despite multiple changes, it has always been closely linked to the medical model of its time [37, 38]. With the further development of medicine, the increasingly mature perspective of social ecology, and the widespread application of the biopsychosocial medical model, people have recognized the complexity of disease etiology (biological factors, genetic factors, acquired factors, psychological factors) [39], especially the impact of social environment on health, thus extending the concept of health to social factors, psychological factors, and individual behaviors, gradually forming a comprehensive and coordinated development of health concept.

Disease spectrum

The definition of health originated from people’s understanding of diseases, that is, to combat diseases and ensure survival. Subsequently, societal progress and shifts in humanity’ s major health challenges have driven continuous expansion of health’ s definitional scope. As disease patterns transform, new health challenges emerge [40, 41]. On the one hand, infectious diseases have been effectively controlled, but chronic diseases closely related to lifestyle, behavioral habits, and life expectancy extension have become the main threats to health. On the other hand, with the further aging of society, aging and the physiological decline it causes have also become problems we must face. These new health challenges require us to rethink and adjust our health strategies [25]. Health is no longer just the absence of disease or disability, but includes the integrity of physical, psychological, and social functions.

Cultural background

Culture plays an important role in the formation and development of health concepts, affecting people’s understanding of health, behaviors, lifestyles, and the provision and acceptance of health services [22, 42, 43]. Cogburn [44] found that the integration and interaction of traditional Chinese, local Chengdu, and modern cultures have promoted the development of health concepts among Chengdu residents. Chan et al. [45] found that the health concepts and behaviors of Hong Kong people are influenced by traditional culture, Western biomedicine, and the unique work culture of Hong Kong. Different countries and regions with different cultural backgrounds also have differences in the content and implementation of health policies [40, 46]. The concept of health presents multidimensional and individualized characteristics, with unique cultural content in different regions.

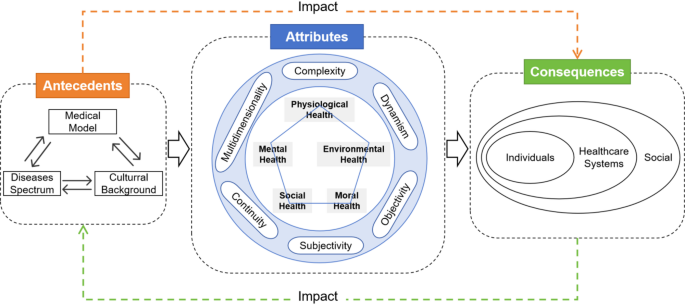

Conceptual attributes of health

Conceptual attributes refer to the key characteristics of a concept, namely the concept features, elements, or constituent features that repeatedly appear in the literature. Conceptual attributes help deepen understanding and grasp of concepts and distinguish them from other similar concepts. Through literature analysis, the attributes of health can be summarized as follows: complexity, multidimensionality, continuity, dynamism, objectivity, and subjectivity.

Complexity

The human body is a complex adaptive system [37]. Health, as a concept with deep connotations and a wide-ranging scope, inherently exhibits diversity arising from its complexity [26, 47]. This diversity arises from the multifarious interactions among individuals, physiology, the natural environment, and the social environment. Rooted in these interwoven relationships, the developmental trajectory of individuals exhibits nonlinear, complex, and changeable characteristics [25]. Understanding the nonlinear, complex, and systemic factors underpinning human development is essential for both analyzing and optimizing health trajectories.

Multidimensionality

Human health is a multidimensional concept, and its diversity is an important feature that leads to real-life implications, representing the most realistic aspect of health [39]. Therefore, interpreting the relationship between health and disease solely from a binary opposition viewpoint, i.e., equating health with the absence of disease, is one-sided. We must consider environmental, psychological, and social factors comprehensively, constructing a comprehensive network of health factors to more accurately explain human health from multiple dimensions [22, 25, 26, 38, 48]. Thus, health needs to be continually enhanced to approach a state where all elements are perfect.

Continuity

Health status exists along a continuum, spanning from optimal health to death—termed the health spectrum [24]. Murphy [49] proposes a health-disease continuum with a threshold, where health and disease coexist in transitional states, and diseases are reversible. However, when diseases worsen beyond a certain threshold, they become irreversible, leading to death [50]. Good and poor health exist not as binary opposites but along a continuum, where disease/disability absence is neither a sufficient nor necessary condition for optimal health [48, 51]. Recognizing this continuity allows individuals to better understand and manage their health conditions, taking appropriate measures to maintain and improve health.

Dynamism

Health is a dynamic construct maintained through continuous balance [22, 52]. Experts propose shifting the focus of the health concept towards adaptation and self-management when facing social, physical, and emotional challenges. This dynamic health concept is related to resilience and coping abilities [25]. Thus, the state of health is not stable but oscillates along the health axis, influenced not only by physiological functions but also by individual behaviors and external environmental factors.

Objectivity

Although health is a complex multidimensional concept, from an objective perspective, it can be measured through a series of clinical medicine indicators [53]. With the continuous advancement of medical technology and a more profound comprehension of the factors that influence health, its scope has significantly expanded. Presently, health considerations encompass not only traditional disease management but also extend to areas such as biomarkers, risk factors, prodromal symptoms, and social behaviors. This expansion represents a more comprehensive and objective evaluation of health determinants [54]. Based on quantifiable biological parameters like blood pressure and blood glucose levels, health assessment criteria have become universal. These data collectively form an objective and healthy scientific benchmark [55], reflecting to some extent the objectivity of an individual’s health status.

Subjectivity

Health and disease are manifestations of the human condition, reflecting individuals’ unique subjective experiences [48, 56]. Because language and conceptual frameworks cannot fully capture human health understanding, health is inherently subjective—not merely a subject for objective scientific inquiry [48]. Self-assessed health (SRH) is increasingly used to reflect an individual’s health status, which to some extent indicates that the subjectivity of health is gradually being valued. Health priorities vary among individuals, who may define health through symptoms, chronic conditions, or daily functioning—making it contingent on personal perception and experience [57]. Simplifying health into a scientific concept, no matter how meticulously designed, cannot comprehensively understand individuals’ cognition and experience of health. Disease is a professional medical concept, but for patients, health relevance lies in whether they experience discomfort or functional impairment [58]. Therefore, health requires exploration from a broad perspective, acknowledging that each individual’ s understanding and experience of health is unique.

Connotations of health

Based on literature analysis and review, we have identified five dimensions of health: physiological, psychological, social, moral, and environmental.

Physiological health

The common understanding of health is predominantly based on physiological health, emphasizing the integrity of the human body structure and normal physiological functions in the biomedical field [59]. This is the fundamental understanding of biomedicine and the main research area of traditional medicine. A classic theory by Boorse [60] defines health as the absence of disease and statistical normality of function—i.e., the capacity to perform typical physiological functions at baseline efficiency. Therefore, the widely used physiological health refers to “normal functional capacity,” which is the intact physiological function [25, 61, 62].

Mental health

Mental health is understood as the absence of disease, positive and balanced state [63]. According to WHO, mental health is a state of mental well-being that enables individuals to cope with life stress, realize their abilities, engage in productive activities, and contribute to their communities [64]. Mental health can be defined as the internal process of self-care, centered on the self-awareness and self-regulation of the human being, in which the person seeks to balance one’s feelings, thoughts and behaviors, intrapersonal, and interpersonal, to approach an optimal state of wellbeing and absence of mental disorders based on universal values and symptoms, and in relation to biological, social, psychological, and environmental factors [65, 66]. Positive mental health involves a sense of well-being, the capacity to enjoy life, and resilience to challenges—transcending the mere absence of mental illness or dysfunction [25, 67].

Social health

Social health can also be called social adaptability. Basri et al. [68] define social adaptation as the ability of individuals to interact with the environment and perform roles in multiple settings (such as work, socializing, and family). The core of social adaptation is the interaction between individuals and the environment, achieving harmony through dynamically adjusting lifestyle and accepting changes. This process spans the individual’s entire life, and environmental changes often stimulate positive changes in individuals [21, 25, 69]. Thus, social health is a vital component of overall health.

Moral health

Moral health represents an emerging dimension in holistic health frameworks, acknowledging how an individua’ s ethical reasoning, values, and actions fundamentally shape health. Moral health is based on moral principles and social unity, by building a just social contract and focusing on social equity and basic human rights, we ensure that people obtain the social conditions necessary for health, thereby fundamentally promoting group health [70]. Moral health exhibits pronounced cultural diversity: Western frameworks emphasize autonomous moral reasoning, prioritizing individual rights and deontological moral judgment [45]. Eastern traditions, conversely, focus on relational morality, centering harmonious integration within collective ethical systems [71]. Despite divergent definitions—ranging from “a clear sense of right and wrong coupled with prosocial responsibility” [73, 74] to “balanced adaptation to social norms”—scholars converge on treating moral qualities as constitutive of health [72]. To avoid the historical risks of equating morality with mere social adaptivity (e.g., complicity under oppressive regimes), we operationalise moral health as the integration of moral cognition, affect, and behaviour: the capacity to critically appraise norms, experience moral emotions, and act consistently with one’ s ethical commitments.

Environmental health

Environmental health can be understood as all physical, chemical, and biological factors outside a person, as well as all relevant factors influencing behavior. aimed at preventing diseases and creating environments conducive to health [21]. With the increasingly severe ecological environment problems, the importance of environmental health for individual and societal health is becoming increasingly prominent. Lerner [75] put forward health as balance between ability and goals in an environment. Focusing on and improving environmental health is a key factor for human pursuit of healthy living, achieving sustainable development, and social harmony [21, 26, 33].

The consequence of health

Results refer to events or situations that occur after the concept exists, namely the outcomes of this concept. Health outcomes primarily encompass impacts on individuals, the social environment, and healthcare services.

Impact on individuals

Health exerts a profound impact on individuals’ lives. Health concepts and cognition determine how individuals treat their bodies, make daily decisions, covering dietary habits, exercise plans, and even lifestyle choices, thereby shaping individuals’ quality of life and sense of happiness [32, 39, 48, 76, 77]. A healthy body is the foundation for fulfilling life roles and responsibilities, providing us with abundant energy, good memory, and stable emotions to cope with life challenges. Conversely, health issues not only affect daily life but may also hinder professional, family, and social performance [38, 78]. The WHO in the “Ottawa Charter” regards health as a resource, believing that health determines individuals’ ability to achieve desires, meet needs, and improve or adapt to the environment [3].

Impact on healthcare systems

Health is generally considered the ultimate goal of healthcare, and research and action in healthcare are based on a common understanding of “health.” Clear health concepts are essential for promoting health, preventing diseases, and providing care [38, 40, 51, 58]. With the improvement of health concepts, the demand for healthcare services continues to increase, and healthcare providers need to adjust and innovate according to the health status of the population to meet the changing needs [25, 39, 46, 76]. To effectively understand, describe, and classify disease conditions, we must address the complex concept of health [79].

Impact on the social

Health has profound impacts on the social. Healthy individuals are full of vitality, actively participate in social activities, support each other, and jointly create a harmonious society [79]. Conversely, health issues may weaken social cohesion, increase social burdens, and even threaten social stability and development. When society faces numerous health problems, healthcare resources and economic burdens may be exacerbated, thereby affecting the overall well-being of society [80]. Conversely, social epidemiology has consistently demonstrated that social inequalities are powerful determinants of population health. Research by Wilkinson [81] & Pickett [82] and Marmot [83] shows that greater income disparities predict poorer health outcomes across multiple indicators [79,80,81,82,83]. We recognize that health is profoundly shaped by income distribution and social hierarchy; consequently, this bidirectional relationship between health and society underscores the importance of comprehensive approaches to health improvement. Ultimately, recognizing the multidimensional nature of health and its intricate connections to social factors is crucial for developing comprehensive health policies and strategies that resonate across diverse cultural contexts.

In summary, the impact of health on individuals and society is multifaceted, involving multiple areas such as lifestyle, healthcare services, and social development. An evident interactive relationship exists between health antecedents and consequences. Shifts in medical models and disease spectra influence both individual health and healthcare systems and social structures due to altered individual health statuses [24, 30]. Different cultural contexts mold individuals’ views on health and their behavioral tendencies. These perceptions and behaviors, in turn, have an indirect effect on health outcomes [46, 50, 54, 84]. Positive health outcomes reinforce healthy prerequisites, creating a dynamic system of interactions. For example, the growing prevalence of chronic diseases among individuals significantly reduces their mental well-being and quality of life. This situation leads to a substantial rise in healthcare costs. This trend imposes an economic burden on society, resulting in labor loss and decreased productivity [22, 25]. Furthermore, as chronic diseases increase the socio-economic burden, it will lead to corresponding changes in health management policies to enhance the prevention and intervention of chronic diseases. The antecedents, consequences and attribute relationships of health are shown in Fig. 2.

Concept diagram of health

Differentiation of Health-related concepts

Health and well-being are two closely related but distinct concepts. In 1997, British Medical Journal (BMJ) highlighted the closer affinity between the WHO definition of health and well-being, as opposed to health itself. Consequently, it was imperative to delineate the concept of health from that of well-being [22, 25, 85]. Oxford Public Health Dictionary [86] defines “well-being” as “a dynamic state of physical, mental, social, and spiritual health that enables individuals to fulfill their potential and enjoy life.” Well-being is not only influenced by health status but also by many other factors such as individual values, living environment, and social status [87]. There is a close relationship between health and well-being. Health, despite some subjectivity, largely focuses on objective indicators such as physical condition and activity levels. In contrast, well-being is concerned with individual subjective experiences that contribute to an individual’s overall life satisfaction and happiness.

Exemplar of the concept

Constructing typical cases aims to better understand the essence of health. An example is as follows:

A 56-year-old man with type 2 diabetes, when asked “Do you consider yourself healthy?” replied, “Quite healthy. My condition isn’t the best. My physical condition isn’t the worst. I have some issues, but I’m working on them. I am a diabetic. I was diagnosed with this disease probably a few years ago. It changed a lot of things in my life, but I’m quite healthy.“ [56] Despite being diagnosed with diabetes, through lifestyle changes and medication therapy, blood sugar control is ideal. He believes that his social functioning has not been affected by the disease, and diabetes even has made his lifestyle healthier. Therefore, he believes that in some definitions of health, due to his diagnosis, he would be considered unhealthy, but in reality, this diagnosis is only part of his broader definition of health, and his health status is even better than before [56]. This case includes six attributes of health definition: complexity, diversity, continuity, dynamism, objectivity, and subjectivity.