Not all superpowers belong to superheroes. In the wild, evolution has granted animals abilities that stretch the limits of biology and imagination alike. Some species heal like science fiction cyborgs, some strike faster than bullets, and others perceive worlds invisible to human eyes. Each of these adaptations serves a purpose. To hunt, to hide, or simply to endure where others would perish.

This is a list of ten extraordinary creatures and the hard science of their powers. From electric eels that generate hundreds of volts to pit vipers that “see” heat. These are nature’s real-life mutants, each reminding us that evolution is the most creative engineer of all.

1. Mimic octopus – The ocean’s ultimate actor

The mimic octopus (Thaumoctopus mimicus) isn’t just good at blending in. It’s also a good actor. On open sand flats with nowhere to hide, it reshapes its body and choreographs movements to impersonate venomous locals like lionfish, sea snakes, and flatfish, discouraging predators that might otherwise pounce. The trick relies on ultra-fast control of chromatophores (for color and pattern), papillae (for texture), and posture to sculpt convincing silhouettes, sometimes switching “characters” mid-scene.

Divers first documented this behavior in Indonesia, noting the octopus goes out searching for food in full view. Confidence born of deception. It’s one of the clearest cases of dynamic, multi-model mimicry in a vertebrate-rich habitat.

2. Electric eel – Zaps its prey into submission

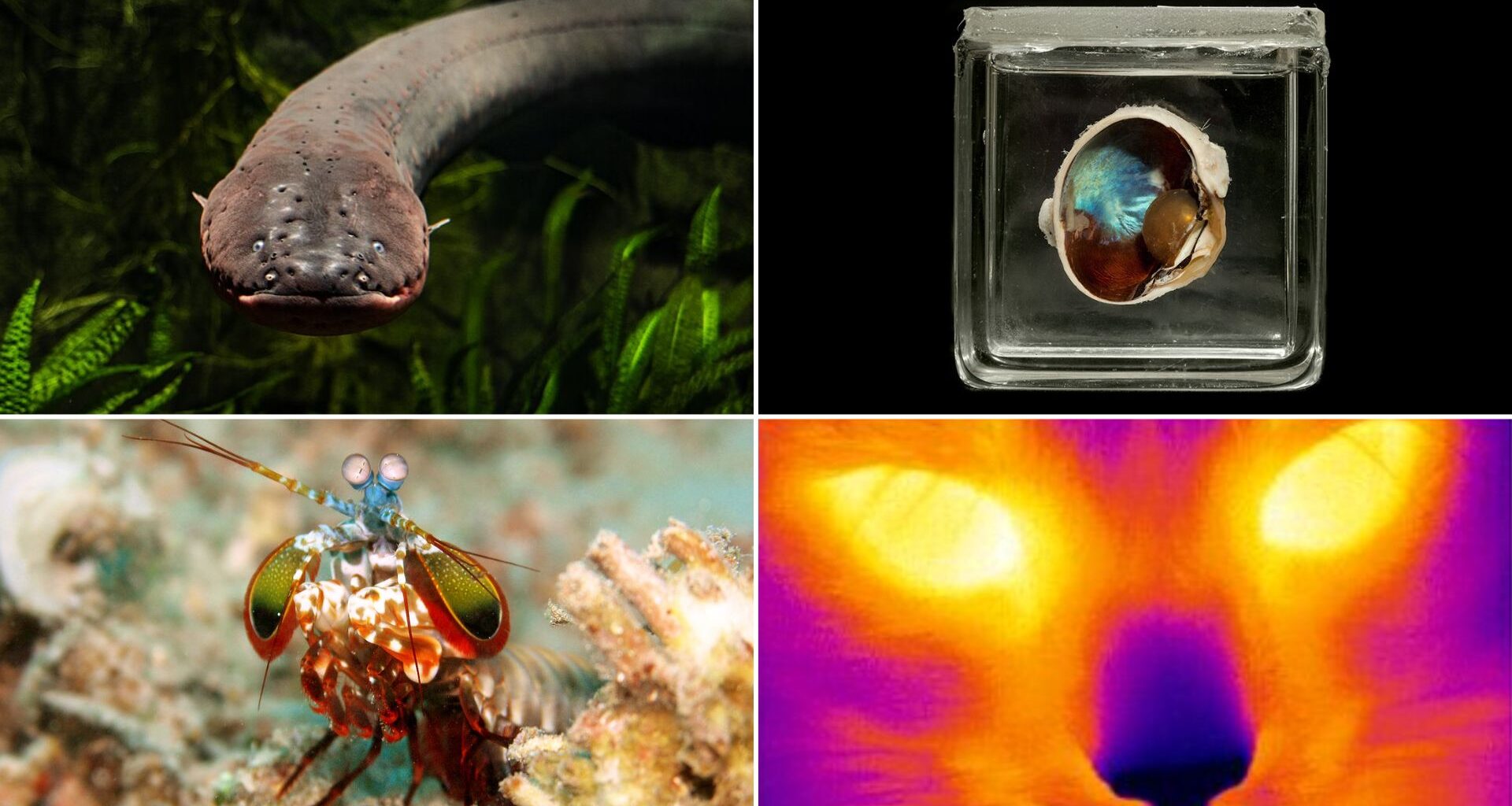

A three meter long Electric eel (Electrophorus electricus) – Wikimedia Commons

A three meter long Electric eel (Electrophorus electricus) – Wikimedia Commons

Electric eels are living battery stacks. 80% of the body is made up of electrocytes wired into three organs (main, Hunter’s, and Sachs’s). Low-voltage pulses map murky water and carry messages. High-voltage volleys (hundreds of volts) stun prey, even remotely “twitching” hidden fish to reveal them.

The eel modulates discharge strength and timing like a taser with multiple settings. Italian scientist Alessandro Volta studied eel physiology to inspire the first battery, and recent work shows eels use doublets, two rapid spikes, to force rapid prey muscle contractions before the knockout blast. Imagine a long, muscular capacitor that can ping, probe, and punch.

3. Axolotl – Regrows limbs, organs, even parts of its brain

The axolotl’s superpower is complete limb regeneration. A feat unmatched by almost any other vertebrate. When it loses a leg or tail, the wound doesn’t scar. Instead, cells at the site revert to a stem-like state, forming a blastema, a miniature limb-making factory that reconstructs bones, muscles, nerves, and skin with flawless precision. Within a few weeks, a fully functional limb re-emerges, complete with digits and joints.

Scientists have observed axolotls regenerating up to five times on the same limb without losing fidelity. Molecular studies show positional “maps,” including retinoic acid gradients and genes like CYP26B1 and SHOX, that guide cells on where to grow. Humans carry a similar genetic toolkit, but their regulation and activity are vastly different. While axolotls can reactivate these genes for full regeneration throughout their lives, humans likely express them only during embryonic development.

4. Black lemur – The jungle chemist

Black lemurs in Madagascar are remarkably resistant to toxins. They have been recorded grabbing toxic millipedes and, rather than avoiding them, chewing and rubbing the secretions into their fur, especially around sensitive areas. The benzoquinones in those secretions are pungent to parasites and mosquitoes, and lemurs sometimes also ingest small amounts, suggesting a mix of topical repellent and internal deworming.

It’s a striking example of animal self-medication (zoopharmacognosy) using invertebrate chemistry as a pharmacy aisle. The intoxicating effect is a key component of this behavior, and the lemurs appear to enjoy the high.

5. Mantis shrimp – Fastest punch in the animal kingdom

The mantis shrimp’s superpower lies in its punch’s sheer speed and force, the fastest strike in the animal kingdom. Its spring-loaded club can accelerate underwater at over 10,000 g (ten thousand times the force of gravity) and reach speeds of 23 meters per second (50 mph). At impact, it delivers a blow exceeding 1,500 newtons, powerful enough to crack open crab shells or shatter aquarium glass.

The strike is so rapid it causes cavitation bubbles, pockets of vapor that collapse with a flash of light and a second shockwave, doubling the damage. But its vision is just as extraordinary. With up to 16 photoreceptor types (humans have three), it perceives ultraviolet and polarized light with astonishing precision. The mantis shrimp is nature’s high-speed boxer with multi-spectral vision, a creature that hits faster than a bullet’s acceleration and sees the unseen.

Bombardier beetle – Fires boiling chemical sprays

When threatened, bombardier beetles mix hydrogen peroxide and hydroquinones with catalytic enzymes in a reinforced reaction chamber, superheating the brew into a boiling, noxious jet. X-ray studies show the spray comes in rapid pulses, like a tiny machine gun, generated by a passive valve-and-membrane system that cycles pressure safely without cooking the beetle itself. The result is a precise, scalding mist that can be aimed at a predator’s face. This beetle is a living chemistry set with armored plumbing and perfect timing.

Naked mole rat – Survives without oxygen and barely ages

The naked mole rat’s superpower is its ability to survive without oxygen, a trait unheard of in mammals. Native to East Africa’s low-oxygen underground tunnels, this wrinkled rodent can endure up to 18 minutes without any oxygen by switching its metabolism from glucose to fructose-driven glycolysis, a process more commonly found in plants.

This allows vital organs like the brain and heart to function even when air runs out. Equally remarkable is its longevity. Naked mole rats live for over 30 years, roughly ten times longer than similar-sized rodents, and show an extraordinary resistance to cancer. Scientists attribute this to their tissues being rich in high-molecular-mass hyaluronan, a sugar-like molecule that prevents uncontrolled cell growth. Together, these traits make the naked mole rat a biological anomaly, a mammal that thrives where oxygen is scarce, cancer is rare, and age seems to slow down.

Reindeer – Changes eye color seasonally

Reindeer eyeball sliced in half – Natural History Museum UK

Reindeer eyeball sliced in half – Natural History Museum UK

The reindeer’s quirk is its ability to change eye color with the seasons, a phenomenon unique among mammals. In the endless daylight of the Arctic summer, the tapetum lucidum, a mirror-like layer behind the retina, glows golden, reflecting light efficiently to prevent overexposure.

But during the sunless winter, when the Arctic stays in near-total darkness for months, the same layer turns deep blue, scattering light within the eye to capture every available photon. This shift increases light sensitivity by up to 1,000-fold, though it slightly reduces visual sharpness.

Scientists discovered that the transformation is caused by subtle pressure changes inside the eye from long-term pupil dilation, which rearranges the spacing of collagen fibers. It’s a striking case of seasonal adaptation — as if the animal physically swaps lenses, trading a golden summer mirror for a blue winter amplifier to survive half a year in darkness.

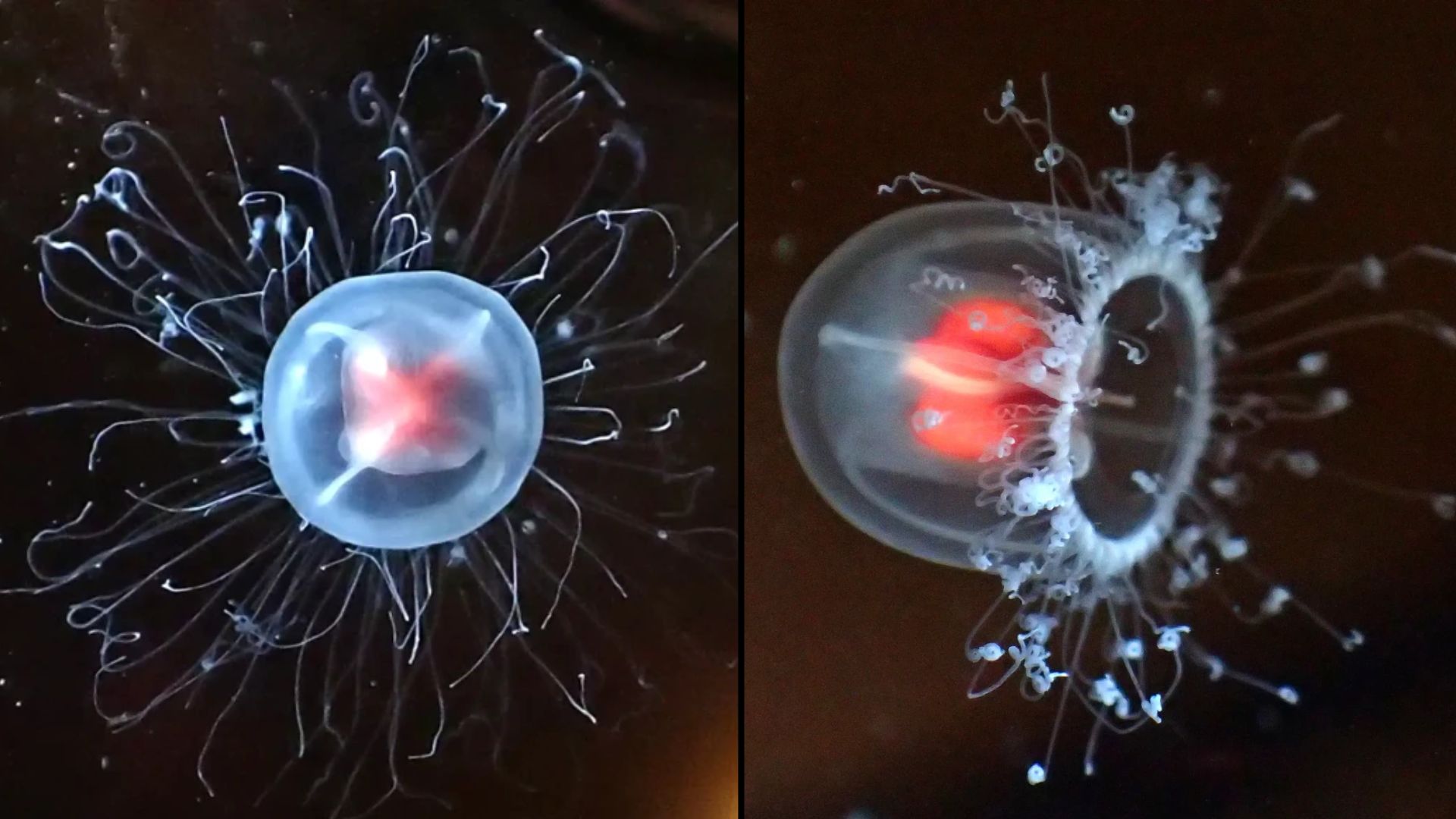

Immortal jellyfish – Reverses aging by reverting to juvenile stage

Tony Wills/Animalia

Tony Wills/Animalia

When stressed, injured, or aging, this tiny hydrozoan, Turritopsis dohrnii, can reverse its life cycle. The free-swimming medusa (A single, free-swimming, umbrella or bell-shaped organism) collapses, cells transdifferentiate, and the animal reverts to a juvenile polyp that buds off new medusae. In principle, the loop can repeat indefinitely, biological “immortality,” though most individuals still die from predators or disease. Under a microscope, the transformation looks like rewinding development itself, tissues dissolving into a cellular soup that reassembles into a new colony. It’s regeneration writ large across the entire body plan.

Pit viper – Built-in infrared vision for perfect strikes

Pit vipers have infrared vision, but not in a way you would imagine. A natural thermal imaging system is built into its face. Each pit, located between the eyes and nostrils, contains an ultra-thin, heat-sensitive membrane packed with nerve endings capable of detecting temperature differences as small as 0.003°C.

When infrared radiation from a warm-blooded animal hits the membrane, specialized TRPA1 ion channels convert that thermal energy into electrical signals. The snake’s brain then fuses these signals with its visual input, forming a detailed “heat map” of the environment. A kind of biological night-vision overlay. With two pits, it can triangulate prey position in complete darkness, striking with pinpoint accuracy even when its eyes are covered. In essence, pit vipers turn invisible heat into visible form, a sixth sense that lets them hunt as effectively at midnight as at noon.