Two millennia ago, Aristotle distinguished between a life lived in pursuit of pleasure, which brings temporary satisfaction, and a life lived according to reason, virtue, and the pursuit of goals, which leads to true happiness. Therapeutic approaches of today tend to agree with Aristotle that fleeting pleasures aren’t enough to make us happy and that a subjective sense of well-being stems largely from the way we live our lives. Three components of happiness have emerged as paramount to well-being across various therapeutic approaches: We need meaningful connections with others; we need to live with a sense of purpose in accordance with our interests and values; and we need to be free from torment by negative thoughts and feelings.

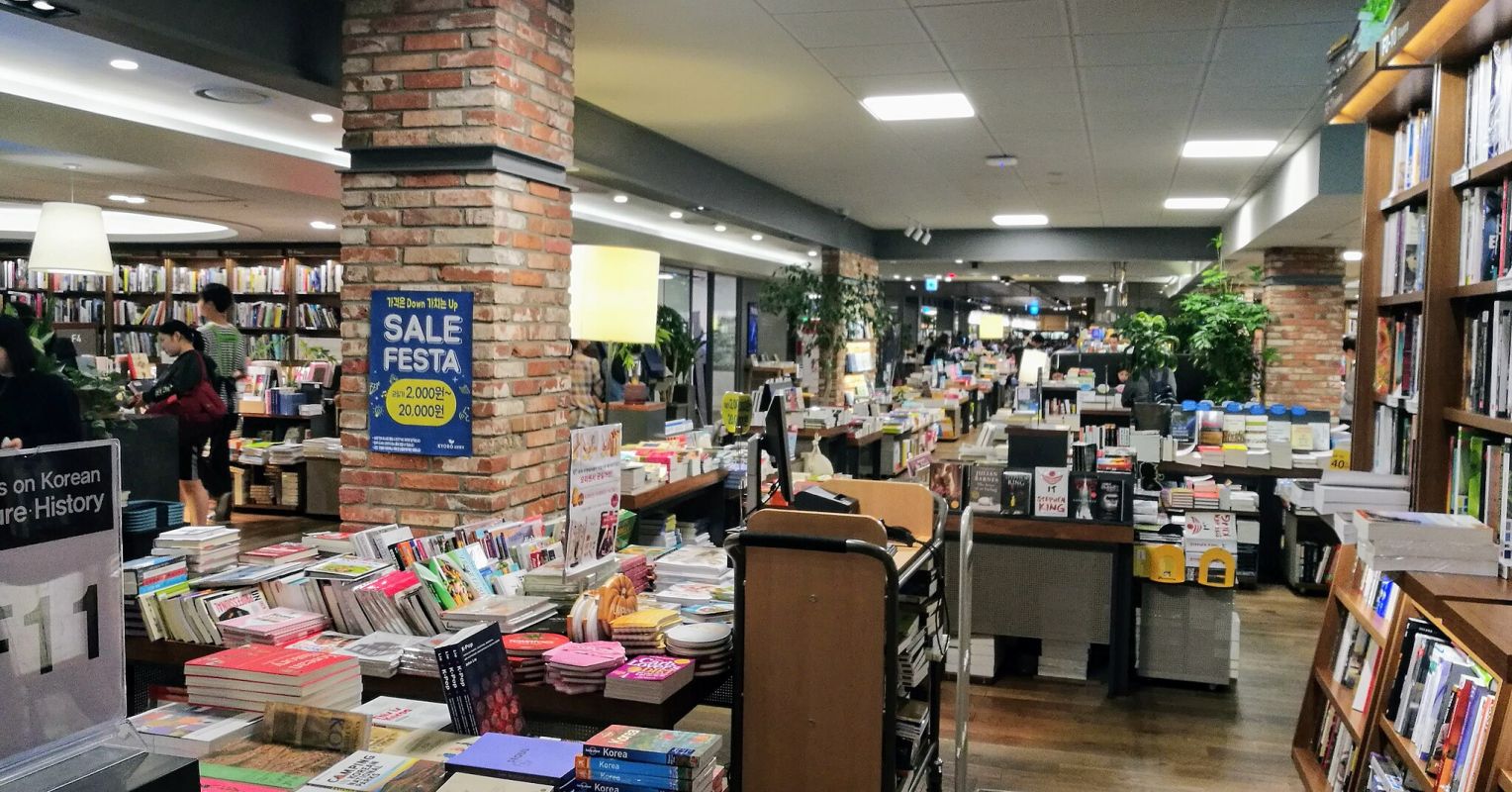

The Korean bestseller Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookshop by Hwang Bo-Reum is a story about finding happiness in a culture where an emphasis on financial and professional success takes priority over our needs for connection and purpose. Although the novel is set in Seoul, its message applies to many other cultures. Indeed, one of the featured books in the shop’s book club is The Refusal of Work: The Theory and Practice of Resistance to Work by David Frayne, an American author. Frayne writes about the negative impact of our obsessive work culture, looking at people who have opted out of the rat race to live more satisfying lives.

Yeongju, the owner of the bookshop, is one such refugee from the work world. She leaves a high-paying job that consumed most of her waking hours to open a bookshop, a choice motivated by her lifelong love of reading. She left a job that was meaningless to her, a career path expected of her by her family. Dedication to an empty pursuit affected other areas of her life, in particular, foreclosing meaningful connections with other people. Her relationships, including her marriage, revolved around a shared belief in a punishing work culture. Her husband is tolerant rather than supportive when, suffering from burnout, she stops going to work. Yeongju ends up leaving her marriage as well as her job.

As the owner of a bookshop, Yeongju is able to live a life in which her work revolves around reading. In addition to bringing pleasure and knowledge, reading can make people more empathetic, and so she feels that in a small way, her bookshop makes the world a kinder, better place. With that goal in mind, she begins to use the shop to create community for her customers, offering book clubs and talks by authors. Through her work, she makes friends, people with whom she feels a genuine connection rather than colleagues whose common ground is the workplace. Through becoming a work “refuser” (of a certain kind of work), Yeongju finds satisfaction, autonomy, and community. She explains, “It’s a huge regret of mine, not having a healthy work life. I had thought of work as stairs. Stairs to climb to reach the top. Now, I see work as food, food that you need every day. Food that makes a difference to my body, my heart, my mental health, and my soul.”

Yeongju is not the only refugee from the work world, and several refusers find themselves within the nurturing atmosphere of the bookshop. Her barista, Minjun, had spent his entire life working toward finding a high-paying corporate job. When his many attempts to do so failed, he simply withdrew from the struggle, becoming listless and aimless. Yeongju hires him as her barista, giving him a generous salary and sufficient time off to have a life outside of work. He soon finds that he doesn’t need a prestigious job with a huge salary to have a good life. He enjoys his daily work, as he learns about the production of coffee and becomes an expert brewer. Like Yeongju, he makes good friends.

With meaningful relationships and work, we are likely to have a sense of well-being. But even so, a person can still struggle with negative thoughts and feelings. Talking back to negativity, a technique of cognitive behavioral therapy and other approaches, works for many people, but not for everyone. Acceptance and Commitment therapy suggests a different way of handling negative feelings, de-fusing from them with a technique called expansion. Rather than answering the negativity, one observes negative thoughts and feelings, sitting with them and accepting them. Such observation allows de-fusion, finding a place that is separate from the torment. Acceptance even opens up the space for seeing things differently and “talking back.”

After she leaves her job and is thriving at the bookshop, Yeongju is still plagued by sadness and guilt about leaving her husband, who had been very hurt by the breakup. She had dealt with her feelings by trying to suppress them. But then she receives a message from him apologizing for not having supported her and forgiving her for leaving him. At that point, she is able to allow her feelings a place. “Images and memories stabbed through her heart,” but by giving them space and acceptance, she immediately feels better and knows she will eventually be able to let go of the grief.

In the course of running a bookshop, Yeongju engages in an informal mode of bibliotherapy, recommending books that she believes might help her customers to better their lives. She might well have suggested Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookshop, which advocates priorities, choices, and actions that have been shown to contribute to happiness.