1. Player Prohibition

Any NRL Player who negotiates, signs or enters into a Letter of Intent, Playing Contract, or any other form of agreement – whether verbal or written – with a football competition, league, or organisation not recognised by the Australian Rugby League Commission (ARLC) as a national sporting federation, will be banned from participation in the NRL and any ARLC-sanctioned competitions for a period of ten (10) years.

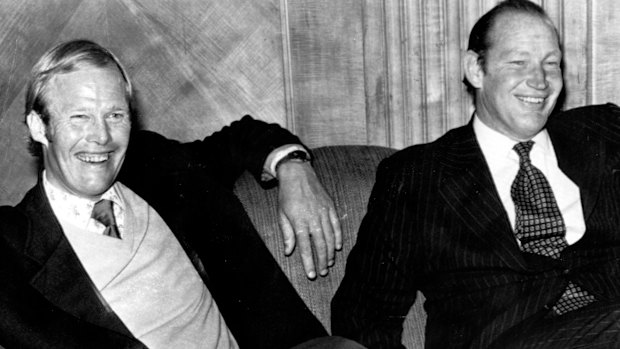

ARL Commission chairman Peter V’landys and NRL CEO Andrew Abdo.Credit: Getty Images

In an attempt to counterbalance, the ARLC rules then further say this:

3. Discretion to Review or Lift Ban

The ARLC retains sole and absolute discretion to review or lift a ban imposed under this provision only in exceptionally extenuating circumstances, to be determined on a case-by-case basis.

What does this mean? And would any of this be spiked by a superior court with requisite jurisdiction if the question were asked?

Without limitation, the following issues are relevant:

Loading

The construction of the rules

Banning a player for a decade, merely for having the temerity to conduct subjectively unacceptable negotiations, is an off-the-leash concept.

To misquote the Hollywood mogul Samuel Goldwyn, a verbal contract isn’t worth the paper it’s written on. What proof of a verbal contract (or fireside chat) the ARLC requires to release the hounds isn’t clear. Nor is it known when the ARLC started compiling a list of “recognised” national sporting federations.

For reasons that’ll follow, no court will agree that banning players for 10 years is legal, unless it’s necessary to protect the ARLC’s legitimate interests for such draconian penalties to be the outcome.

Procedural fairness, or the complete absence thereof

A 10-year ban is career-ending for a rugby league player. Fixed and self-executing sanctions extinguish an affected person’s right to be heard and to make submissions about mitigating factors.

The ARLC’s rule doesn’t provide for any flexibility, discretion, or nuance, except if a person demonstrates the existence of not only extenuating circumstances, but such circumstances which also are exceptionally so. The rule also doesn’t afford any express right to a player to test the evidence relied on to deploy the operation of the rule in the first place.

The seminal English High Court decision in Greig v Insole concerned bans imposed on Test players (including Bill Lawry’s Channel Nine sparring partner, Tony Grieg) defecting to World Series Cricket during the upheaval of the late 1970s. The judgment stands as authority for many principles, including that blanket or arbitrary bans imposed by a sports governing body can be unlawful if the affected athletes are denied natural justice and a fair process.

Former England cricket captain Tony Greig with Kerry Packer in 1977.

Restraint of trade

There’s no controversy that a professional rugby league player engages in trade, even by the narrowest legal definition of the term.

The ARLC and its NRL competition is, in a sense, a monopoly. Let’s be frank, for a professional rugby league player, where else can you ply your trade? The English Super League, maybe, but nowhere else. Banning a rugby league player from playing rugby league isn’t the equivalent of McDonald’s banning a burger flipper for talking to KFC; that person could always go work at Oporto and not suffer.

Policies that operate to govern elite and professional sports have restraining barnacles stuck everywhere. Salary caps limiting player incomes; draft rules dictating where a player must ply their trade; and policies governing how an athlete can switch allegiances and compete internationally for a second country after they’ve already played under another flag – each are examples of restraints on trade.

The player draft in the AFL exists only because the players’ association acquiesces; otherwise, a legal challenge would bring uncertainty. There’s no draft in Australian rugby league; the legality of a player draft was struck down in the early 1990s.

If a current NRL player were banned by the governing body for a decade, for just engaging in negotiations with R360, does that withstand legal scrutiny?

Zac Lomax is contracted to the Parramatta Eels through to the end of 2028. If he engaged in “negotiations”, now, with Rugby 360, and was banned without ever signing any contract, that’d mean he’s not only banned from coming back into the NRL in the future, but that he’d also be prohibited for three years from fulfilling the obligations of his employment with Parramatta, if the R360 negotiations sour.

Leaving aside the grievances of Jason Ryles and the Eels’ paymasters who might be lumbered with a banned player, it’s difficult to understand how the ARLC might justify the construction of its rules as going no further than is necessary to protect the ARLC’s legitimate interests in the NRL competition.

Fair Work Act considerations

NRL players are employees of their clubs. The idea that actions taken by a player – including actions that proceed to no outcome – might ipso facto invoke a decade of excommunication might well be sufficient to enliven the adverse action provisions of the Fair Work Act.

Competition and Consumer Act considerations

Loading

This is just me hypothesising of course, but if there’s any evidence that exists, of any chatter between the ARLC and the likes of Rugby Australia, along the lines of acting together in a robust way to come down like a sledgehammer on anyone who dares talk to R360 – think international bans; 10-year professional bans – then this conceivably could end up being classified as cartel conduct.

In many ways, professional rugby and rugby league compete for the same pool of elite players. If there’s a concerted plan to kill the new shark in the swimming pool … Well, you get my drift.

Practical reality

With all these points duly observed, a banned player would require the intestinal fortitude to challenge. That case might be fought to the death, with all the usual vagaries and horrendous expense of litigation chucked in.

If the ARLC lost, it’d definitely appeal. The wheels of justice turn slow, and each revolution is wildly expensive. And that’s not a nice place for a footballer to be in.