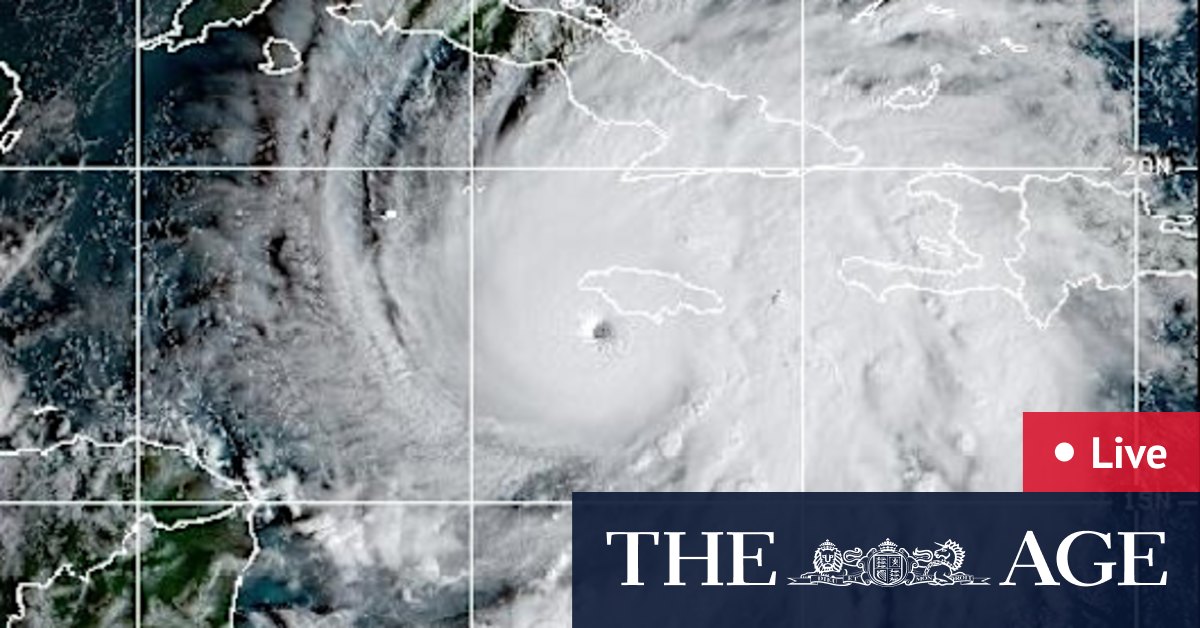

While Melissa’s power – with estimated maximum sustained winds of 298 km/h, according to the National Hurricane Centre – is in focus, the storm’s sluggish pace has amplified fears among forecasters and officials.

This combination of slow forward movement and blistering internal winds has made this storm particularly dangerous.

Slow-moving hurricanes allow the high winds within them – the rotational speed of the wind – to batter their impact zone for longer and dump larger amounts of rain.

Research shows tropical cyclones are moving significantly slower across the globe as the climate warms.

Between 1949 and 2016, the global translation speed of tropical cyclones decreased by an average of 10 per cent, one recent study shows. This reduction directly impacts the amount of rain a given area receives from a cyclone, as slower-moving storms linger longer, dumping more rain. This effect is compounded by the fact that warmer atmospheres hold more water vapor, leading to increased rain rates within tropical cyclones.

According to an analysis by Yale Climate Connections, Melissa intensified rapidly due to the extreme heating waters across the central Caribbean, where record sea surface temperatures have been recorded through October, as they have been around the world, including around Australia.

“That part of the Atlantic is extremely warm right now – around 30 degrees Celsius, which is two to three degrees Celsius above normal,” Akshay Deoras, a meteorologist at the University of Reading, in the United Kingdom, told Associated Press.

“And it’s not just the surface. The deeper layers of the ocean are also unusually warm, providing a vast reservoir of energy for the storm.”