“Who can predict what form grief will take,” says Subimal Das, 49, a sculptor in Kolkata.

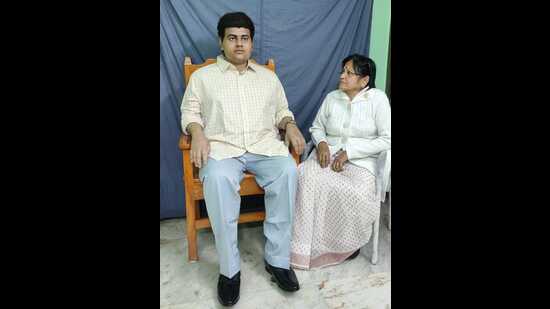

![]() PREMIUM Silicone sculptures of Samit Dutta’s parents, Arun and Hena Dutta, in Kolkata.

PREMIUM Silicone sculptures of Samit Dutta’s parents, Arun and Hena Dutta, in Kolkata.

He has been taking on some unusual commissions lately.

For 25 years, he says, he largely sculpted celebrities (in hyper-realistic silicone). Mahatma Gandhi for a museum in Patna, Virat Kohli for an amusement park in Haridwar, Rabindranath Tagore for the West Bengal Assembly building.

Since 2021, business has picked up, with the bulk of it coming from a new direction. Families are approaching him for statues of: a missing son, a wife lost suddenly to the pandemic, a beloved professor.

He has created about 50 such sculptures in four years, for families from West Bengal, Sikkim, Assam, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. The figures he crafts are often dressed in the clothes of the lost loved one, and eventually positioned to fit into the house they once inhabited. Prices start at ₹3 lakh.

Each likeness is first shaped in clay. At this stage, the family is invited to offer feedback.

“It is important to capture the person’s essence, not just their likeness,” Das explains. This typically involves making adjustments to the eyes, nose, or the crook of a smile.

MEMENTO MORI

Gita Bhattacharjee with the likeness of her son, Abhishek, who went missing when he was 28.

Gita Bhattacharjee with the likeness of her son, Abhishek, who went missing when he was 28.

“He was all I had after I lost my husband at 28. Then I lost him when he was 28,” says Gita Bhattacharjee, 65, who commissioned a sculpture of her missing son Abhishek Bhattacharjee last year, after seeing Das’s work in local news reports.

The retired labour department employee from Kolkata spent 10 years looking for her son, before she decided to seek some closure. He is now immortalised, and will keep her company as she ages, she says. “It helps to see this version of him, as my memory slowly falters.”

Elsewhere, Dr Bipasha Goswami, 30, a veterinary surgeon, and her brother Soumyadeep Goswami, a medical student, commissioned a likeness of their father, in 2022. Nemai Chandra Goswami was a retired professor in Suri, West Bengal, and died of pneumonia, aged 68.

“His loss shattered us,” Dr Goswami says. “But the sense of community we felt, with so much love pouring in for him from his peers and students, has helped us through it. The statue allows us to maintain a continuing bond that photos simply cannot offer.” His students visit his likeness often. Some stay to chat, sharing memories and stories about him.

The idea for this tribute came after they saw a video online of a young woman from Tamil Nadu who received a bust of a deceased parent as a gift, at her wedding.

“With the statue in our home, I still get to touch my father’s feet and seek his blessings every time I have a big day ahead of me,” Dr Goswami says.

MEMORY PROJECTS

The Goswami famiy with a silicon statue of Nemai Chandra Goswami, a retired professor in Suri, West Bengal, who died of pneumonia, aged 68.

The Goswami famiy with a silicon statue of Nemai Chandra Goswami, a retired professor in Suri, West Bengal, who died of pneumonia, aged 68.

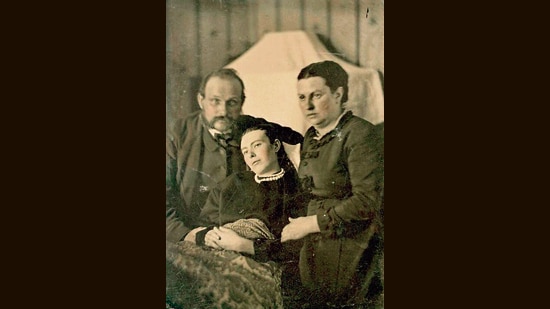

In form, these tributes echo practices that first emerged in the early years of affordable photography, in the mid-1800s. In those years, death portraits immortalised a loved one. For these special shoots (often the only photograph ever taken of the person), the deceased was positioned in a favourite chair, or at rest in a bed.

“With time and technology, our relationship with grief and how we express it evolves,” says clinical psychologist Priyanka Varma of The Thought Co, who has specialised in grief counselling. After photographs, there were home videos. Now, AI bots offer to chat in a deceased person’s voice.

Turn the clock back and, before photography, there was mourning jewellery, in which locks of hair from a loved one were typically encased in a locket or a ring.

And before that, as far back as 13,000 years ago, fragments of what were once petals have been found at Palaeolithic gravesites.

A Victorian-era death portrait (the girl in the centre is deceased). (Wikimedia)

A Victorian-era death portrait (the girl in the centre is deceased). (Wikimedia)

We have always struggled with mourning and remembrance. “We strive to preserve memories as they are lost to time, and hyper-realistic statues and digital avatars, enabled by new technology, offer new ways to help us do this,” Varma says.

It could make letting go that much harder, she points out.

“It ought not to become a way to evade reality. This is important,” she says.

STILL LIFE

Das says he still thinks about the first such request he received, from a government employee in Kolkata, in the middle of the pandemic.

Tapas Sandilya had just lost his wife to Covid-19 and was devastated that she died without family near her. As with so many in that terrible time, loved ones had to be kept away.

Sandilya was still devastated when he approached Das. “Despite his family’s objections, he wanted a likeness of her,” Das says. “His unwavering conviction moved me.”

An array of mourning jewellery brooches containing hair from a lost loved one. (Wikimedia)

An array of mourning jewellery brooches containing hair from a lost loved one. (Wikimedia)

In Jhargram, West Bengal, a statue of Swarnab Bagchi, who died at 26, sits poised with his guitar. His parents have surrounded his chair with some of his favourite things.

For Samit Dutta, 49, an advocate at the Calcutta high court, the two statues of his parents mean he wakes up less alone. He lost his mother, Hena Dutta, when he was 18, and his father, Arun Dutta, to a stroke, three years ago. “I find myself sitting in front of them when I am bogged down by a typically tough case,” he says. “It helps to try to think of what they would say to me if they were here.”