What India is doing, will do, and should do—to not just survive but thrive in the chaos unleashed by Trump. Subscribe here

Good morning [%first_name |Dear Reader%],

You are reading our Premium subscriber-only newsletter Make India Competitive Again—a weekly commentary on what India should do to thrive in the chaos unleashed by Trump

Enter your email address to receive a daily curation of our latest newsletters, stories, and podcasts.

Do you think Agastya Sen, the pot-smoking, Marcus Aurelius-reading protagonist of English, August, would have even considered a career as a civil servant now? Not a chance. To his kind—Sen is the son of a mandarin-turned-state governor and he has a Yale-alumnus friend—working for the government is now as unimaginable as being part of a nonprofit focused on rural sanitation.

Even 20 years ago, when I was in college, a former bureaucrat asked why we should spend years trying to pass the notoriously hard civil-service exams when we could work just as hard to make it into an Indian Institute of Management. We would make more money than he could ever dream of, and, more importantly, we wouldn’t be doing politicians’ bidding.

But implicit in that argument is privilege far beyond the vast majority of India’s reach. Most desperately want a job. Any job. India’s official unemployment rate in June is 5.6%, but to many experts, the number could well be imaginary. Seventeen of the 50 economists polled by news agency Reuters pegged the jobless rate at between 7% and 35%.

“The whole thing to me is really throwing dust in your eyes. You say this is the unemployment rate, the growth rate—quite often, they don’t make much sense. We have a massive employment problem and that is not reflected in the data,” said Pranab Bardhan, professor emeritus of economics at the University of California, Berkeley.

“Most Indian workers are underemployed. If you are able-bodied and you did not work for any time, not even one hour in the last six months, unless you are rich, how did you feed yourself? So you scrounge around and do something. And then you are employed. Now what does that employment mean?” asked Bardhan.

So it should surprise no one that the civil services, which include 20 streams, including local administration, policing, diplomacy, and revenue, are still coveted. In fact, too coveted.

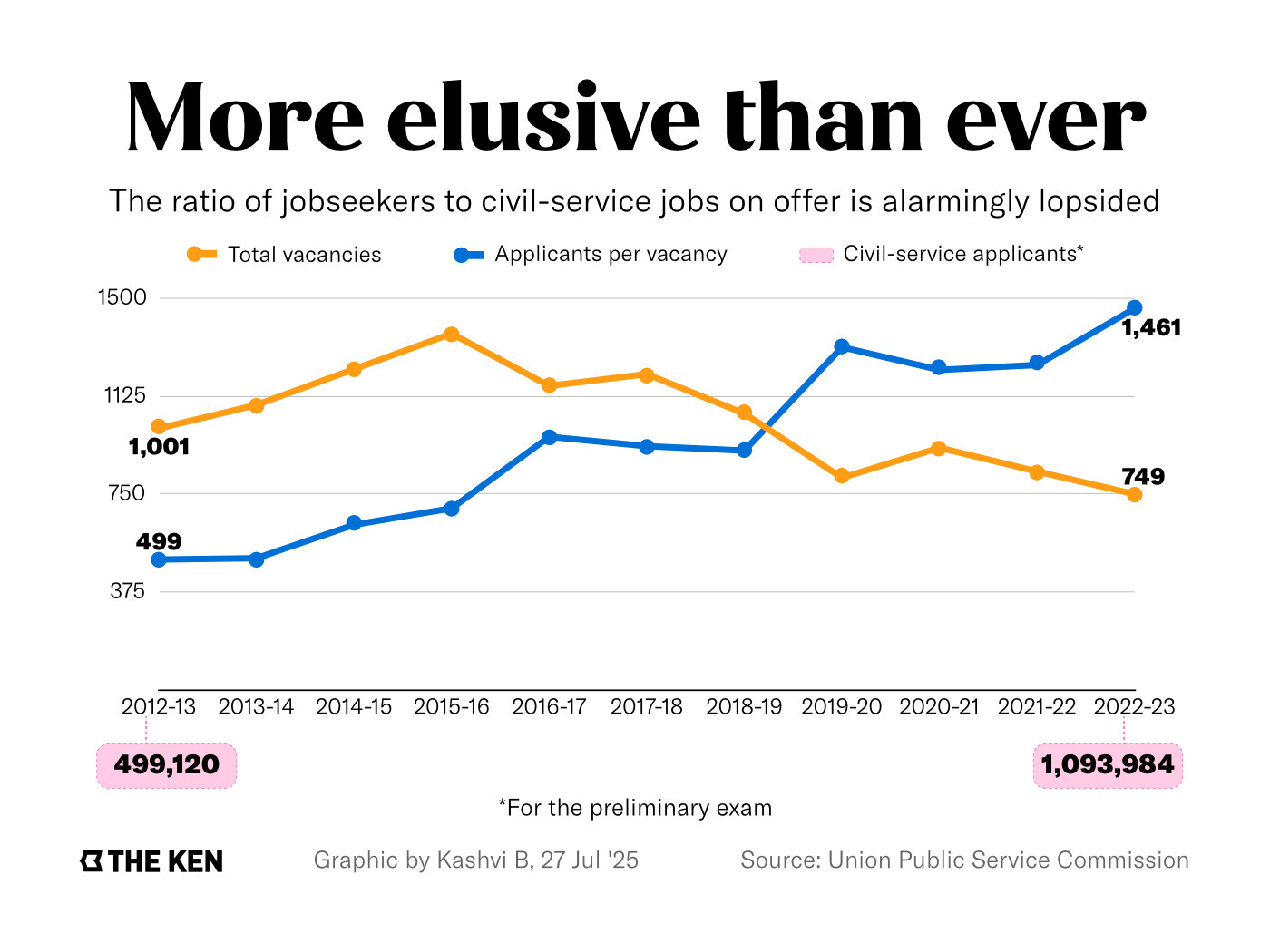

In the decade up to FY23, the latest year for which data is available, the number of applicants for the preliminary exam more than doubled, to 1.1 million. But the number of applicants fighting for each vacancy almost tripled.

The surge is startling, especially when the ranks of new college graduates only expanded 40% in roughly the same period.

The Narendra Modi administration knows it can do nothing to dissuade the hordes of candidates. Many think, and rightly so, that being a public servant is their best shot at upward social and economic mobility. So the central government wants to give the applicants something more to look forward to than these few hundred jobs every year.

Make India Competitive Again • EPISODE 16

India’s puzzling fix for the civil-service-job obsession

It speaks to the perilous state of employment in the country

Don’t have The Ken app? Install now

Enter yet another state scheme with a tortured acronym: Pratibha Setu, or Professional Resource And Talent Integration—Bridge for Hiring Aspirants. With this, the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC), which conducts the Government of India’s civil- and defence-service exams, wants other arms of the government and even private companies to hire the unsuccessful candidates.