The Waratah Super Battery – the grid’s new giant shock absorber – has been subject of many superlatives since it was first envisioned several years ago and sent its first power to the grid late last year.

It is variously described as the most powerful battery in the country, and likely the world, and the biggest machine of any sort to be connected to Australia’s main grid. It has also been described as the most innovative and extraordinary, and now – for the moment, at least for some – it also the most notorious.

News of the “catastrophic failure” of one of the project’s transformers has finally emerged from its owner Akaysha Energy. It has stunned many in the industry, and has predictably been used as cannon fodder for the anti-renewable brigade who say that it is yet more proof that the green transition cannot be successful.

But – like many of these issues – the problem is likely less around the battery technology itself than other factors, including the decisions taken by those involved in its development. The answers to those questions may not be known for a while, but it is already the source of intrigue and the subject to considerable scrutiny and speculation.

Akaysha itself has said as little as it can about the incident, which occurred in the early morning of Saturday, October 18. It has described the events in an internal memo as a “catastrophic failure” at one transformer, and in an official statement as a “temporary loss of capacity” due to a transformer outage.

“During ongoing Hold Point testing to transition the battery to full capacity, issues were identified with two transformers,” it said in a public statement. It said in its internal memo that one of the three transformers will have to be replaced.

The company is frustrated because it occurred just as it was preparing for one of the final steps in the commissioning process before full commercial operations. The battery, already delayed six months, mostly due to weather related issues, now faces another six month wait, at least, before reaching full commercial operations.

How and why did it happen?

The incident has sparked a host of questions: How and why did it happen? When can it be fixed? What are the implications, if any, for market prices and coal closures? What is the impact on Akaysha itself? What does it mean for its contract?

In the absence of a detailed explanation, there is a lot of second guessing going on, mostly focused on the choice of transformer (why not use more smaller ones), the alleged lack of full transformer redundancy, and – inevitably – even the decision to award a contract to build the grid’s biggest machine to a company with no prior track record.

Akaysha staff are well-respected and seasoned professionals. But eyebrows were raised when – as a start-up with no corporate track record – the company won the tender in late 2022 for one of the country’s most important projects.

The EoI documents distributed by EnergyCo in April, 2022, stated quite clearly that one of the pre-requisites were: “The applicant has demonstrated capability of successfully delivering projects or services of similar size, type, value and complexity.”

Akaysha, which has since evolved rapidly from a start-up into the country’s biggest operator of big batteries (mostly still in construction or commissioning), insists the event does not affect its financing arrangements.

But there is great speculation about the impact of the delays – will it be six months as currently advised to AEMO, or will it be longer? Can another transformer be built in that timeframe? Can the entirety of its “shock absorber” contract still be served with just two out of three operating transformers?

Akaysha has a 5.5 year contract to provide most of its capacity – up to 700 MW and 1,400 MWh – to act as a giant shock absorber, under a contract known officially as the System Integrity Protection Scheme.

It was seen as a critical part of the plans to fill the gap to replace the country’s biggest coal generator, the 2.88 GW Eraring facility just up the road.

If the contract cannot be filled, the implication is that less renewable energy capacity can be imported into the state’s major load centres from their locations to the state’s north, south and west.

Lower supply inevitably leads to higher prices. It might even influence the ability of the Eraring coal generator to be closed in the new timeframe of August, 2027. Eraring’s owner, Origin Energy, is clearly considering its options, even as it completes its own 700 MW, 2,800 MWh battery at the site of the coal generator.

Transmission company Transgrid, which has oversight of the Waratah project, says in a regulatory filing that it was first advised of delays to the project in early March this year, and later that month asked the Australian Energy Regulator for a “variation” of the revenue streams under the SIPS contract.

But it is not clear if this “variation” was a reduction of revenue, or just an agreed postponement of its starting date. The details are blacked out.

Even if it was a postponement, there is speculation that the triggering of the “interim” contract – running at half the capacity of 350 MW, 700 MWh – will complicate any issues about shifting the date on the full contract.

But little is known about the details of the contract. Even the scale of the payments to be made to Akaysha, via Transgrid, remain blacked out in all relevant AER documents, because of the “commercial sensitivity” of the numbers.

Big, sturdy machines

There is surprise in the industry that the 350MVA 330/33/33kV transformer failed so spectacularly and needs to be completely rebuilt or replaced.

These are sturdy machines, (Akaysha’s are Australian-made by the highly regarded Wilsons Transformers and are pictured at the top right of the photo above), they weigh around 300 tonnes, are 14 metres long and 7m wide, and cost more than $10 million.

Transformers are conventional technology, but they do fail. The most spectacular recent failure was at a substation near Heathrow Airport in March this year that caused widespread power outages. In India, according to one report, there were 17 transformer failures in its main grid just in the first six months of this year.

The most common problems cited with transformer failures are age, lack of maintenance, heating, overloading and electrical stress, such as sudden high voltage surges.

In the case of Waratah, we can safely rule out age and wear and tear, which leads some to speculate that it could have been the result of the high cycling and sheer scale of the battery project that was too much for the equipment.

Waratah is the most powerful battery in Australia, and its 850 MW capacity rating means it is also the biggest machine of any type to be connected to the grid, bigger than the 750 MW unit at Queensland’s Kogan Creek coal fired power station (which incidentally tripped this week after returning from repairs).

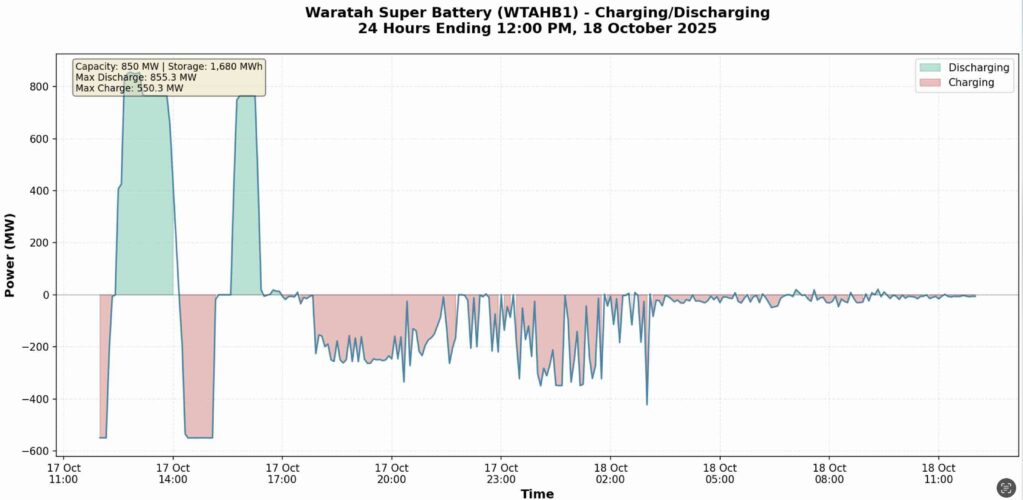

But batteries don’t just discharge, they charge as well, and the swing between high levels of charge to discharge and vice versa can be more than 1.5 GW. This is exactly what the Waratah battery was doing in the days leading up to the event in mid October.

Highly charged

As Renew Economy reported at the time, it discharged at maximum capacity for the first time on October 10, setting a new record for the country, and data shows it was doing similar levels of charging and discharging on Friday, October 17, one day before the incident (See graph above).

Waratah admits in its brief public statement that the “issues” were identified during testing in the transition to full capacity. Did that put too much stress on the transformers? Was there a fault in the transformer equipment?

Some outside observers say the fact that all transformers were taken off line as a precaution, and problems found in a second unit, suggest that is one possibility.

So, how quickly can the broken unit be repaired? The minimum run time to build a new machine is said to be six months, and the current wait time is said to be 12 to 24 months.

Screenshot

Screenshot

The fact that Wilsons is an Australian company should help. It may well be asked to drop everything to prioritise the new one. If they can do that, even transporting the machine from Melbourne to Sydney, via massive road trains and multiple prime movers, is a dedicated operation that will take at least one week.

The photo above, from a media release in 2024 celebrating the delivery of the machines, illustrates the scale of the road transport.

In a statement, Wilson Transformer Company said is supporting the investigation into the issues at Waratah which it said involved two transformers.

“WTC is working closely with its project partners to undertake a detailed inspection and analysis to determine the root cause,” it said.

“The investigation is reviewing all possible scenarios, including those related to influences that may be external to the transformer. This process requires thorough investigation which may take some time.

“One transformer has experienced an issue and a second transformer has been de-energised as a precaution. The third transformer on the Waratah site remains fully operational. “

Marek Kubik, a co-founder of US-based battery technology giant Fluence, which is building many of the big battery projects in Australia, and now a director at Saudi venture Neom, says it is a reminder that big projects have multiple points of vulnerability.

“It is worth remembering that even the most bankable ESS (energy storage system), or indeed (worth stressing) any flexibility or generation asset, is at the mercy of single or near single-point HV (high voltage) failures: this asset already benefits from 3 points of failure rather than one,” he wrote on LinkedIn.

“As we scale into the gigawatt battery era, this is a reminder that the balance-of-plant risk becomes increasingly significant.”

For Akaysha, it will have been a sobering event. Owned by global investment giant Blackrock since 2022, it has been rapidly propelled from mere “startup”, or “upstart”, to the biggest player in the market, recently overtaking Neoen with the most battery capacity operating, under construction or contracted, according to Rystad Energy.

So great has its impact been that CEO Nick Carter was even included, along with the Pope, King Charles and Australian foreign minister Penny Wong, as one of Time Magazine’s Climate100 leaders.

Clearly, the sheer scale and novelty of what Waratah is designed to do it has captured the imagination of observers overseas. That Time list came out in late October, after the transformer incident had occurred, but before it had been publicly revealed.

Not the first problem

It is not the first problem to have hit the project. Its battery supplier, the US-based Powin, which was supplying its first project in Australia, filed for bankruptcy protection earlier this year, because of problems largely blamed on the policy changes in the US.

Powin was chosen because of its lower pricing. The installation of the battery packs were far enough down the track for the bankruptcy protection move to not visibly impact the Waratah project, although Carter took off to the US to snap up many of Powin’s laid off employees.

Akaysha is working on another five major battery projects in Australia – Orana, Brendale, Ulinda Park, Elaine and Deer Park, totalling more than 6 gigawatt hours, and it has other projects in the pipeline and has been active in Japan.

The next phase of the Waratah project is now likely to be at least partly played out in the courts – as fingers are pointed in various directions as to the responsibility of the delays and failures and contractual obligations. Akaysha is being assisted by outside corporate communication advisors to help on its wording.

Note: Renew Economy sent a bunch of questions to Akaysha’s PR firm on Tuesday, but had not received a response before publication on Wednesday afternoon. We will update if we do.

Renew Economy also reached out to Transgrid for comment. This story has been updated to include a response from Wilson Transformers and a correction to the weight and dimensions of the transformer. We used the transport load dimensions, not the transformer itself.

Giles Parkinson is founder and editor-in-chief of Renew Economy, and founder and editor of its EV-focused sister site The Driven. He is the co-host of the weekly Energy Insiders Podcast. Giles has been a journalist for more than 40 years and is a former deputy editor of the Australian Financial Review. You can find him on LinkedIn and on Twitter.