Wifredo Lam, a Cuban-born painter, is not exactly little-recognized. Even during his day, he was considered a cornerstone of the Surrealist movement, befriending André Breton, Pablo Picasso, and others through connections forged in France, where he first gained fame. But Lam’s work beyond Europe, which he left in 1941, remains lesser-known outside the Caribbean—something that a new retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art aims to remedy.

Curated by Christophe Cherix and Beverly Adams, along with Damasia Lacroze and Eva Caston, the MoMA show, billed as Lam’s first US retrospective, comprises some 130 works, including rarely seen paintings and drawings that attest to the artist’s engagement with Afro-Caribbean traditions such as the Lucumí religion. Among those pieces is one newly acquired work from MoMA’s holdings that is making its public premiere after years in a private collection. More on that piece and others below.

Read a full review of the show here.

Image Credit: ©Wifredo Lam Estate/Adagp, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Capriles Cannizzaro Family Collection

Some of Lam’s earliest works were made in Spain, where he finished out art school. This one responds to the horrors of the Spanish Civil War.

Image Credit: ©Wifredo Lam Estate/Adagp, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Museum of Modern Art

Fata Morgana was produced as an illustration for a book by André Breton, who has commonly been credited as the leader of the Surrealist movement.

Image Credit: ©Wifredo Lam Estate/Adagp, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Museum of Modern Art

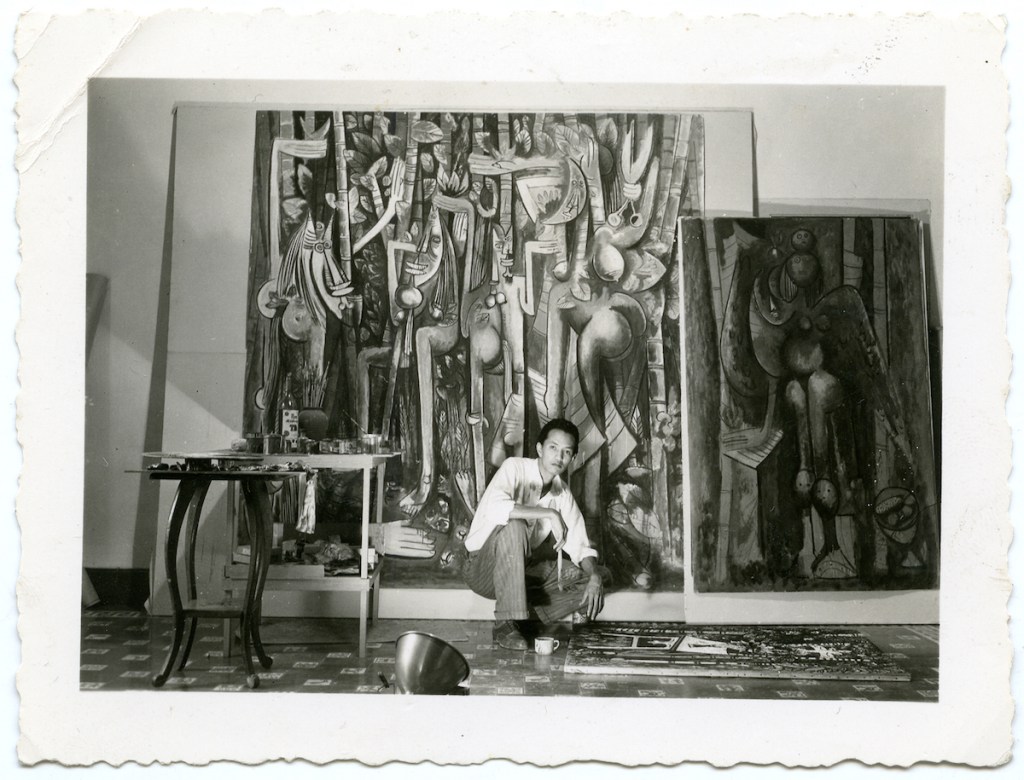

Commonly regarded as Lam’s masterpiece and produced upon his return to Cuba in 1941, La jungla situates a group of beings amid sugarcane. Their faces resemble African masks, to which Lam often referred.

Image Credit: ©Wifredo Lam Estate/Adagp, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2025/Private Collection

Lam continued producing dazzlingly colored paintings of beings in settings dense with foliage during the 1940s. This painting’s title could allude to an instrument played by an angel.

Image Credit: ©Wifredo Lam Estate/Adagp, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Museum of Modern Art

Grande Composition spent years in a private collection abroad. The Lam show’s co-curator, Christophe Cherix, coaxed the collector in parting with the piece, which has now entered MoMA’s collection.

Image Credit: ©Wifredo Lam Estate/Adagp, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Private Collection

During the ’50s, Lam began making abstractions that contain no obvious figures. The MoMA show asserts that these, too, are rooted in his Afro-Caribbean perspective, alluding to the landscape of Cuba.

Image Credit: ©Wifredo Lam Estate/Adagp, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Collection Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, New York

A horse-like figure known as a femme-cheval recurs throughout Lam’s oeuvre, which frequently elides the boundary between humanity and other animals.

Image Credit: ©Wifredo Lam Estate/Adagp, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy McClain Gallery/Private Collection

Damballa, the deity mentioned in the title of this painting, recurs throughout traditions of the African diaspora, including Vodun.