Iron deficiency prevents the body from making enough hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. Credit: Unsplash.

Iron deficiency prevents the body from making enough hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. Credit: Unsplash.

Iron deficiency rarely makes headlines. Yet it shapes the lives of nearly two billion people. Fatigue, headaches, weakened immunity—symptoms so common that many barely connect them to a lack of a single element. For young women, the burden is especially heavy. And for years, the main tools against it (yes, pills or fortified foods) have changed very little.

Now, researchers in Zurich say they have built something new.

And they did it with oats.

Nano-Nutrition

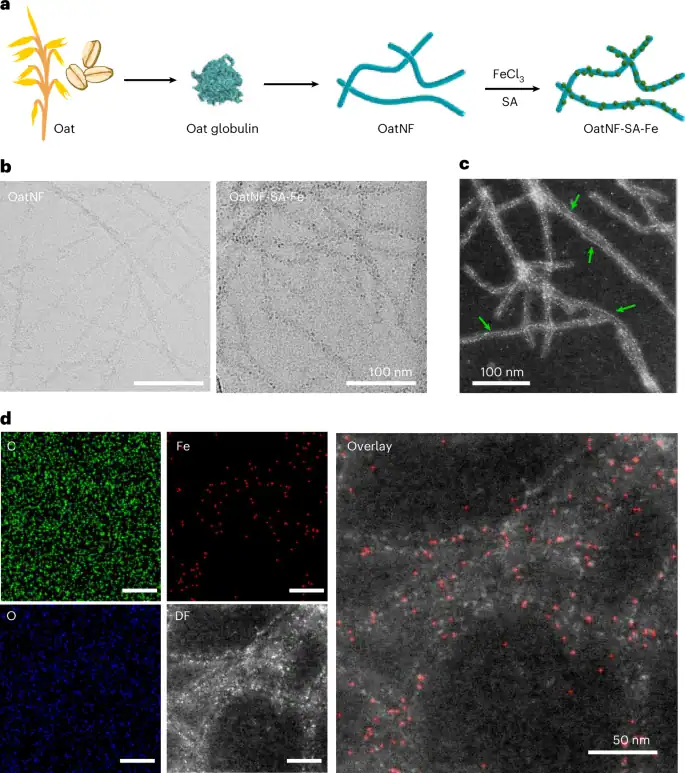

In a new Nature Food study, scientists at ETH Zurich describe an iron supplement built from oat proteins and iron nanoparticles. The latter are small structures that line up along protein fibers like beads on a thread.

The result is a plant-based hybrid that delivers iron to the body far more efficiently than today’s most common supplements.

“This is important because they are more likely to suffer from iron deficiency than meat-eaters,” said ETH professor Raffaele Mezzenga, referring to people on plant-based diets, in a statement.

The technology emerged from years of research into protein nanofibrils. These long, threadlike structures form when proteins are heated and uncoiled. In this case, the team extracted oat globulin, dissolved it under acidic conditions, and heated it until the proteins assembled into nanofibrils. When mixed with iron salts and the reducing agent sodium ascorbate, subnanometer iron particles formed and anchored themselves to the surface. Electron microscopy revealed the particles arranged in a necklace-like pattern along each fiber.

One detail mattered most: stability. Iron nanoparticles tend to clump but the hybrid prevented this. And once stabilized, the iron dissolved rapidly under stomach-like acidity, making it easier for the body to absorb.

A schematic illustration of the fabrication process of the OatNF-SA-Fe hybrid. Credit: Nature Food, 2025.

A schematic illustration of the fabrication process of the OatNF-SA-Fe hybrid. Credit: Nature Food, 2025.

A promising idea in the lab must still prove itself in real life. So Mezzenga and his collaborators turned to Thailand, where iron deficiency anemia remains widespread.

There, a team led by nutrition scientist Michael B. Zimmermann tested the oat-iron hybrid in 52 women ages 18 to 45. Each woman received three supplements on different days: the new compound, a control version made with a different chemical process, and ferrous sulfate—the gold-standard iron supplement recommended by the World Health Organization.

According to the study, the hybrid delivered 1.76-fold higher absorption when taken with water compared to ferrous sulfate. Even when mixed into a polyphenol-rich meal (foods that typically block iron absorption), the new compound still performed 1.65-fold higher than the standard.

Zimmermann and Mezzenga summarize the stakes bluntly in the scientific paper: “OatNF-SA-Fe hybrid demonstrated exceptional FIA,” (fractional iron absorption).

A second version of the supplement made with sodium hydroxide, which encourages iron to form larger ferric particles, also performed well—about 77% as effective as ferrous sulfate—but offered even better sensory qualities in reactive foods.

An Absorption Problem

Iron in the body is tricky. It oxidizes and reacts with foods, turning juices brown or leaving metallic aftertastes. In the gut, it binds with polyphenols in tea, coffee, and fruit. And when absorption is low, unabsorbed iron can irritate the intestinal lining.

The new hybrid aims to address several barriers at once.

The team explains that the supplement is tasteless and colorless. Jiangtao Zhou, the study’s lead author, reinforced the point: “Sensory properties play a major role in consumer acceptance of food additives.”

“On examining the organs and tissues of the rats, we did not find any evidence of nanoparticles or nanofibrils accumulating or possibly causing organ changes,” Mezzenga said.

That safety matter loomed large early in the research. The protein fibrils resemble amyloid structures, the same kinds associated with Alzheimer’s disease. But, as the team emphasizes, these fibrils are made from hydrolyzed edible proteins and are digested rapidly. In both rats and laboratory simulations of human digestion, the fibers broke down completely.

And so did the iron.

Iron deficiency remains the leading cause of anemia worldwide. The World Health Organization estimates that about one-third of women of reproductive age experience anemia, a number that has barely budged in decades. Many existing fortification strategies fail because the iron changes the color or flavor of foods or because the iron simply remains unavailable to the body.

The new oat-based compound was designed to fit into that unmet niche. It can dissolve in water or juice, mix into yogurt, and fortify cereals. It uses ingredients that are cheap and abundant: oat proteins and iron salts.

That flexibility could extend the technology well beyond iron. Mezzenga noted in the ETH press release that he hopes to adapt it to combat other deficiencies, such as zinc and selenium.

The team has already secured patents in Europe and the United States.

Iron fortification has always walked a tightrope: a nutrient essential to life, yet chemically fussy and biologically delicate. The oat nanofibril hybrid offers a way to keep iron stable, palatable, and absorbable.

It is not a silver bullet. But it is an elegant piece of molecular engineering aimed at one of humanity’s simplest nutritional problems. And if future trials confirm its promise, millions could eventually benefit.

As Mezzenga put it: “Our new iron supplement has enormous potential for successfully combating iron deficiency in an economic and efficient way.”