Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most prevalent form of sleep apnea. It is caused by multiple episodes of upper airway collapse during sleep, resulting in obstruction, with or without decreases in oxygen saturation (SpO2), and sleep interruptions.1 In the United States, 59% of men and 41% of women met the criteria for OSA in 2024.2 The incidence of OSA increases with aging, with 90% of men and 78% of women diagnosed between age 60 to 85.3 Research shows that OSA plays a significant role in poor health outcomes, but proper treatment can reduce negative health outcomes and enhance quality of life.4

Screening for OSA includes patient history and physical examination findings, as well as sleep questionnaires. A polysomnogram is used for a definitive diagnosis of OSA.1

Pathophysiology and Etiology

During normal sleep, the dilating muscles of the upper oropharynx contract in response to inspiration to avoid a buildup of negative pressure. In OSA, however, the mechanism of the dilating muscles of the upper oropharynx is altered, or the oropharynx is narrowed, causing a buildup of negative pressure that causes the oropharynx to collapse. This action leads to an apneic episode, resulting in a decrease in partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) and an increase in partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2). This stimulates brain arousal to alert the body to breathe. The recurring collapse of the upper oropharynx results in temporary oxygen desaturation, causing sleep interruptions and excessive daytime sleepiness.4

Anatomical abnormalities seen in the upper airway play a crucial role in the development of OSA.5 Structural abnormalities, including soft tissue enlargement or narrowing of the oropharynx caused by fat deposition around the neck, can make the upper airway more prone to collapse.6 The differences between structures of soft tissue enlargement and narrowing of the oropharynx increase the risk of the upper airway collapsing.7

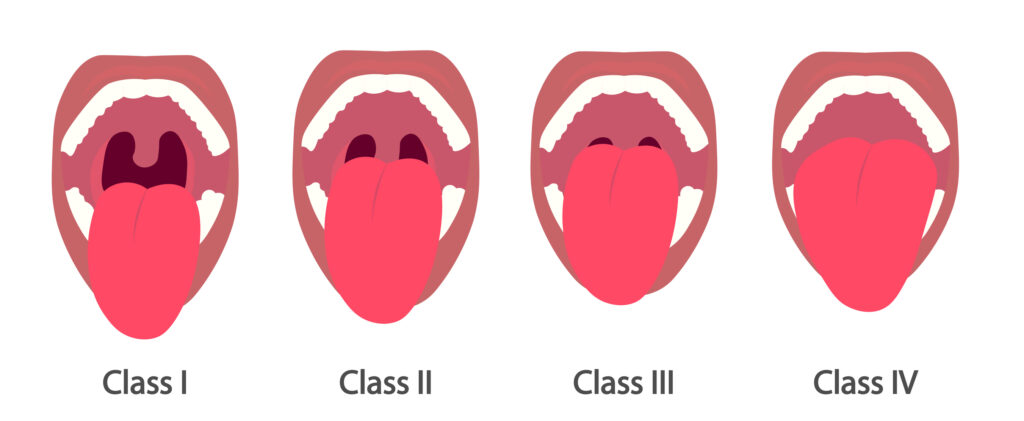

Upper airway narrowing can be evaluated using the Mallampati score, which assesses the size of the tongue compared to the oropharynx. The Mallampati score is classified as follows:

Grade I: tonsils, pillars, and soft palate were clearly visible

Grade I: the uvula, pillars, and upper pole were visible

Grade III: only part of the soft palate was visible

Grade IV: only the hard palate is visible

Mallampati Score, an assessment to predict the difficulty of airway management during intubation. Credit: Getty Images

Mallampati Score, an assessment to predict the difficulty of airway management during intubation. Credit: Getty Images

According to Becelar de Athayde et al, Mallampati classes III and IV were accurate predictors of moderate to severe OSA.7

Other medical disorders that can play a role in collapse of the upper airway include diabetes, Down syndrome, congestive heart failure, and atrial fibrillation.8 Insulin resistance and autonomic nervous system dysfunction related to diabetes can also impact upper airway stability.9 The association between atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea may be because of underlying cardiovascular disease and hypertension.10

Clinical Presentation and Screening

Patients evaluated for OSA may complain of symptoms that include hypersomnolence, snoring, gasping for air, or observed episodes by the patient or a bed partner.8 When evaluating a patient with suspected OSA, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale can be used to evaluate the severity of sleepiness. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale ranges from 0 to 24, and results greater than 9 should be evaluated with a polysomnography (PSG). The STOP-BANG questionnaire is also widely used as a screening tool (Table 1).8

Table 1. STOP-BANG Questionnaire

ItemQuestionSnoringDo you snore loudly?TiredDo you often feel tired or sleepy throughout the day?ObservedHas anyone observed you stop breathing during your sleep?Blood PressureDo you have or are you currently being treated for high blood pressure?BMI≥ 35 kg/m2Age> 50 yrNeck circumferenceMale ≥ 43 cm ;

Female ≥ 40 cmGenderMaleBMI, body mass index Scoring Interpretation: Low risk: 0-2; Intermediate risk: 3-4; High risk: > 5

A physical examination of a patient with suspected OSA may find a large neck circumference measuring greater than 40 cm in women and 43 cm in men, a deviated nasal septum, a crowded oropharynx, or a body mass index (BMI) greater than 35 kg/m2.1 Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is also a common finding in patients with OSA. A study by Pardak et al estimated that 40% to 60% of people with OSA also suffer from GERD.11

Table 2. Subjective and Objective Measures of Obstructive Sleep Apnea

SubjectiveObjectiveAssessmentPlanTreatment“I’m tired all the time.”STOP-BANGOronasopharynx examHome sleep testAmerican Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines“My bed partner c/o my snoring.”Neck circumferenceNarrow palatePolysomnography CPAP/BiPAPWeightBMI >35 mg/k2Large tongueENT for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomyMandibular advancement device ESS score > 9Mallampati Hypoglossal nerve stimulation Co-morbidities: T2DM, HTN Weight loss with GLP-1

BiPAP, Bilevel positive airway pressure; BMI, body mass index; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; ENT, Ears nose and throat; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Score; HTN, hypertension; T2DM, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

When to Refer to a Sleep Specialist

Patients with an Epworth Sleepiness Scale score greater than 9, or those who answer yes to 3 or more STOPBANG questions, should be referred to a sleep specialist for evaluation of OSA. Patients who are asymptomatic are not candidates for a sleep study unless they have occupations that make sleepiness hazardous to themselves or other civilians, such as truck drivers or pilots.8

The presence and severity of OSA are determined by a PSG, which records brain waves, oxygen saturation levels, eye, head, and leg movements, as well as the rise and fall of the chest and abdomen.11 The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) is defined as the number of apnea or hypopnea events that occur during sleep divided by sleep time in hours.12 Home sleep apnea testing (HSAT) is also available for OSA testing. The patient can use this testing option at home; however, HSAT does not measure brain waves to evaluate brain activity from sleep to wake.13

Diagnosing OSA involves the number of times a patient experiences an apnea episode and is categorized into 3 levels of severity13:

Mild: 5 to 15 events per hour

Moderate: 15 to 30 events per hour

Severe: greater than 30 events per hour

Diagnosis of OSA is made when the AHI is greater than 5.

The next step is to utilize Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) titration during the sleep study to identify a pressure that is adequate and successful at reducing the number of apnea episodes.14

Management and Treatment

Management and treatment of OSA involves a multistep approach. Lifestyle changes and weight loss are typically recommended in addition to CPAP therapy. CPAP is the mainstay of treatment, especially in patients with an AHI greater than 15 or those with lower AHI but excessive daytime sleepiness.15 The effectiveness of CPAP therapy has been shown to improve quality of life, decrease blood pressure, decrease sleepiness, and decrease the overall severity of OSA.15 Medicare offers CPAP reimbursement if therapy meets a minimum criterion of at least 4 hours for 70% of the nights throughout a month.15

The hypoglossal nerve stimulation (HGNS) is another treatment option for patients with OSA. HGNS is a device that generates electrical impulses to stimulate the hypoglossal nerve and is used in the treatment of moderate-to-severe OSA in patients who are unable to tolerate CPAP therapy.16 The stimulator is attached to the hypoglossal nerve, which controls the genioglossus muscle. When the nerve is stimulated, it allows the genioglossus muscle to contract, thus preventing upper airway collapse.17 The HGNS sense changes in inspiratory effort, resulting in contraction of the genioglossus muscle, movement of the tongue forward to allow widening of the airway, and a decrease in the level of critical closing pressure.17 Although the HGNS is an option for treatment of severe OSA, contraindications for placement of this device include a BMI greater than 32 kg/m2, severe underlying lung disease, and those who are or plan to become pregnant.17

In the United States, 59% of men and 41% of women met the criteria for OSA in 2024.

According to Heiser et al, after a 12-month study comparing CPAP therapy and HGNS, an AHI less than 15 was observed in 87% of CPAP and 84% of HGNS patients; an AHI of less than 10 in 81% and 74%, and an AHI of less than 5 in 59% and 51%, respectively (P = 0.626; P = 0.268; P = 0.269).18

Studies reveal OSA and BMI have a positive correlation — as BMI increases, the severity of OSA also increases.19 Weight loss has been shown to decrease the severity of OSA as well as decrease the AHI.20 Carneiro-Barrera et al conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the relationship between weight loss and severity of OSA. The authors found that an 8-week interdisciplinary weight loss and lifestyle intervention significantly improved OSA severity and other outcomes compared with usual care alone. At 8 weeks, 45% of participants in the intervention group no longer required CPAP therapy; at 6 months, 62% of participants in the intervention group no longer required CPAP therapy.20

A Mandibular advancement device (MAD) is a treatment option for patients with mild-to-moderate OSA or for patients with severe OSA who cannot tolerate CPAP therapy.21 These devices allow the mandible to shift forward, or anteriorly, which results in a widening upper airway and a decrease in the ability for the upper airway to collapse during sleep.21 The advantages of MAD versus CPAP include convenience, ease of use, and patient adherence. Although the effectiveness of MADs in decreasing apnea episodes is lower than CPAP therapy, the overall efficacy of MADs is similar to CPAP therapy due to patient acceptance of treatment.22

There is emerging evidence that OSA is a heterogeneous disorder. The root cause and pathophysiology are frequently multifactorial.23 Chu Y et al states that the increased predisposition for upper airway collapse, decreased upper-airway dilator muscles, instability in ventilation control, and a diminished arousal threshold collectively contribute to the development and severity of OSA. The authors discuss treatment options targeted at a specific OSA trait in order to have a precise and accurate treatment for individual patients. Although CPAP therapy is aimed at treating OSA, understanding the cause of a patient’s OSA may result in improved outcomes.23

Conclusion

The frequency of OSA is increasing as the rate of obesity increases. It is crucial for primary care providers to be aware of the presenting signs and symptoms of OSA when providing care to their patients.24 Once treatment is initiated and compliance is attained, symptoms tend to improve. Treatment with CPAP, MAD, or HGNS is not curative, and patients will require lifelong use of these devices. Primary care providers and sleep specialists are vital to monitoring symptoms and compliance to lower the risk of cardiac or cerebral events associated with OSA.25