The Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) was set up to accelerate the build-out of renewable energy by using auctions for underwriting contracts to enable 26 GW of renewables and 14 GW of dispatchable capacity by 2030.

Whilst battery storage projects are booming, only a handful of solar and wind projects successful in CIS tenders have subsequently reached financial close and proceeded to construction.

The slow progression of solar and wind projects with CIS awards has sparked debate about the causes. Some projects are still navigating planning and transmission processes and not yet in a position to reach financial closure1.

However, market participants report competition between projects has led to prices being awarded by the CIS that are not sufficient for projects to satisfy debt funders and reach financial closure – which means they require a power purchase agreement (PPA) with a retailer (a ‘utility PPA’) or an electricity buyer (a ‘corporate PPA’).

As retailers have signed very few PPAs with new solar and wind projects in recent years, a lot of weight is effectively being placed on the Corporate PPA sector to fill the gap.

The Corporate PPA market has become an important source of investment in renewables – around 60 per cent of the renewable capacity built since 2017 has contracted a Corporate PPA at some point in their development.

However, the Corporate PPA market is not equipped to carry this weight. The Federal Government has been saying that around 6000 MW of solar and wind generation needs to be installed annually to reach the 2030 target.

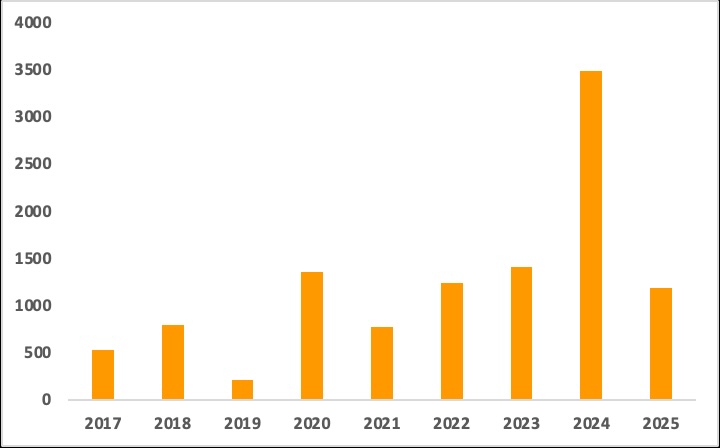

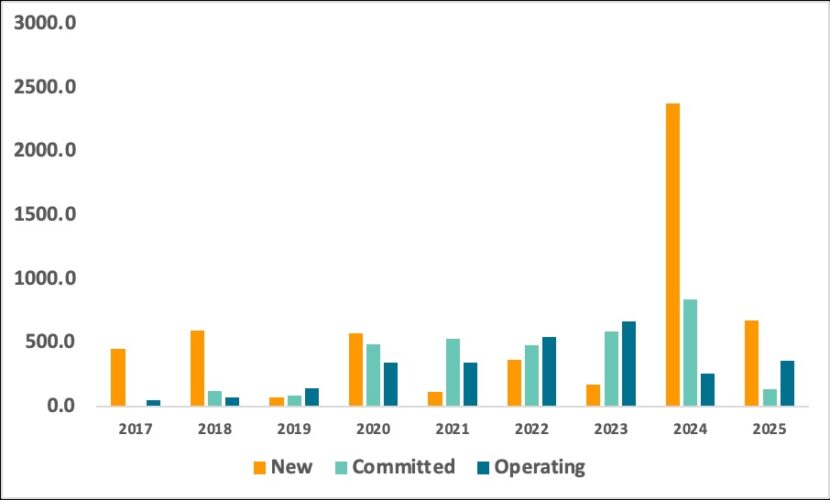

In most years since 2020, the Corporate PPA deal volume has ranged between 1 – 1.5 GW – and the volume of Corporate PPAs with projects before financial closure has been around 500MW or less (outside last year when 2 GW+ was signed by large resource companies).

The NEM review has focussed debate on the ‘tenor gap’ (the deficit in buyers that will sign PPAs longer than 7-years) but a more urgent priority is developing options to fix the ‘offtaker gap’ (the deficit in buyers that will sign PPAs to enable solar and wind projects to reach financial closure).

This article examines trends in the Corporate PPAs, implications for the CIS and options for fixing the offtaker gap2.

The Capacity Investment Scheme and PPAs: Government Auctions 2.0

Whereas earlier government auctions (such as the Victorian Renewable Energy Target) provided solar and wind projects with revenue certainty that took them out of the market for a PPA, the Capacity Investment Scheme is designed to keep projects in the market for a PPA.

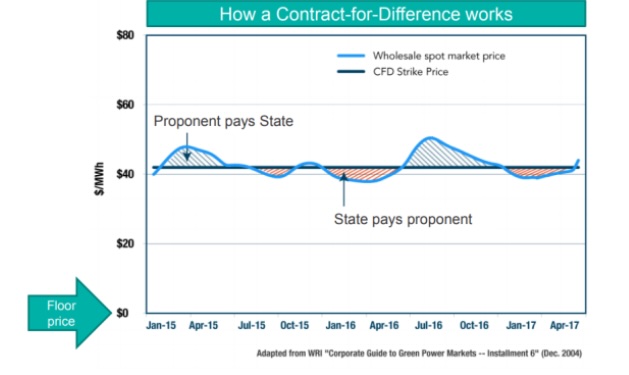

Earlier auctions offered contracts-for-difference that the government topped up to the agreed strike price for all output despatched to the grid if the wholesale market price was lower and vice-versa.

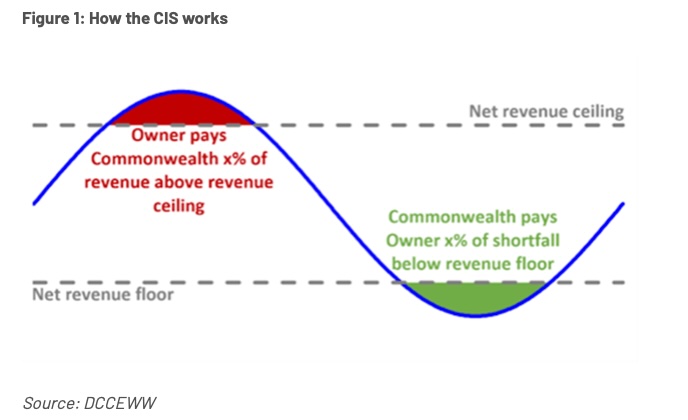

Under the Capacity Investment Scheme, the winner bidder receives an options contract with a ‘cap and collar’ structure which is designed to provide the project with the minimum revenue required to secure debt.

In practice, whilst the prices of winning bids are not made public, it has been commonly observed that intense competition between projects for a CIS award has led to prices that are too low for solar and wind projects to secure debt finance and reach financial closure.

Consequently, solar and wind projects with CIS awards are still seeking PPAs to reach financial close. Unless they are able to finance off their own balance-sheet or take the risk of operating merchant in the wholesale market, there are three types of offtakes:

a PPA from a retailer for their own portfolio (a ‘utility PPA’);

a PPA with a ‘government retailer’ or utility (e.g. CleanCo, Queensland); or

a corporate renewable PPA from a public or private sector electricity buyer, either signed directly with the buyer (a ‘wholesale PPA’, a financial derivative separate from the retail electricity contract) or intermediated by a retailer (a ‘retail PPA’).

However, in practice, options 1 and 2 are limited.

The three large ‘tier-1’ retailers (around 70% market share), which hold portfolios of fossil fuel and renewable assets, have signed very few PPAs with solar and wind projects since the achievement of the mandatory renewable energy target in 2020. Tier-2 retailers are limited by their scale and sometimes credit ratings to be offtakers for new renewable energy projects.

The Queensland government owned utilities have been major players since 2020, but the election of a Liberal-National Party government with an anti-renewables platform means that will surely no longer be the case.

Can the Corporate PPA Market fill the gap?

The corporate PPA market has become an important part of the Australian renewable energy sector. In 2025, as with most years since 2020, the deal volume is likely to between 1 – 1.5 GW (advisers say there are other deals that have not yet been announced).

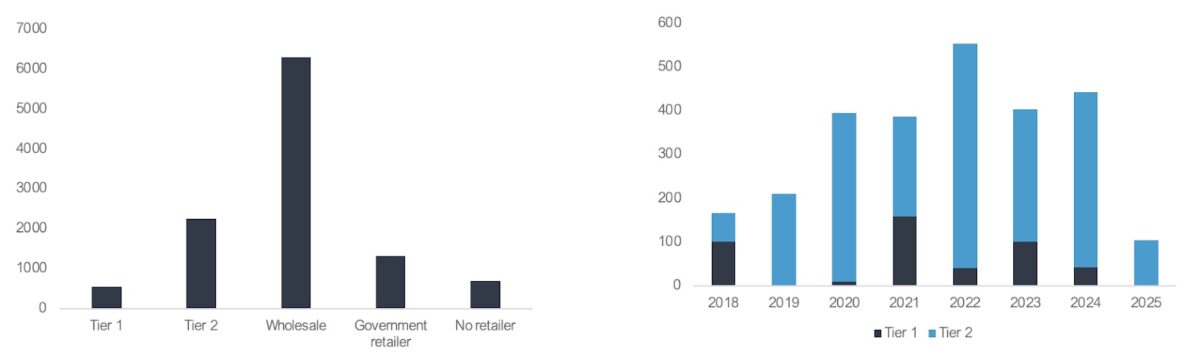

Figure 1: Corporate PPA Deal Volume (MW), 2017-2025

Outside last year, when there were some very large PPAs signed by Rio Tinto, the volume of Corporate PPAs with projects before financial closure has been around 500MW or less.

Figure 2: Corporate PPA Deal Volume (MW), by project stage, 2017-2025

Corporate PPAs signed after financial closure can and do play important roles – by creating a demand-signal for retailers to contract more capacity with projects and improving financial stability for projects across their life-cycle.

However, it is offtakes with projects before financial close that are required now. The Federal Government has been saying that around 6000 MW a year of solar and wind generation needs to be installed to reach the 2030 target.

Could the corporate PPA market scale up? This can’t be predicted but there are likely to be limits to the scale of the Corporate PPA market.

Firstly, market participants observe there are a number of factors that are currently leading to buyers postponing contracting.

– sustainability targets are the major catalyst for most PPA buyers and there is still some time before 2030 targets.

– a price gap has opened up between buyer expectations and PPA prices as underlying project costs have risen.

– there are major uncertainties hanging over the energy transition which make it difficult to evaluate the value of a PPA;

– forward pricing could be very different depending on, for example, if coal closures are postponed or proceed.

In this context, some buyers are holding off making contracting decisions.

Secondly, in the Corporate PPA market, the majority of contracting has been done either by large buyers directly with projects via wholesale PPAs or the tier-2 retailers.

Figure 3: PPA Volume (MW) by counter-party (left) & PPA Volume (MW) by Retailer, 2018 -25

Generally, wholesale PPAs are negotiated by buyers with the scale (50MW+) and credit ratings deemed to be a creditworthy off-taker by debt financiers. Most of the wholesale PPAs in recent years have been signed by large resource companies such as Rio Tinto and BHP with projects outside the CIS.

We are a long way off covering the demand of large industrials and resource companies so we could see years like 2024 in the future – but there has been no sign to date that there are sufficient buyers in Australia to see this scale consistently.

In the retail PPA market, it is the tier-2 retailers that drive activity.

However, most of the retail PPAs are signed after projects reach financial closure – partly because smaller retailers may lack the size and credit rating to be a creditworthy offtaker at scale for new projects and partly because there is a wider market of buyers for PPAs which are lower risk after they have reached financial close.

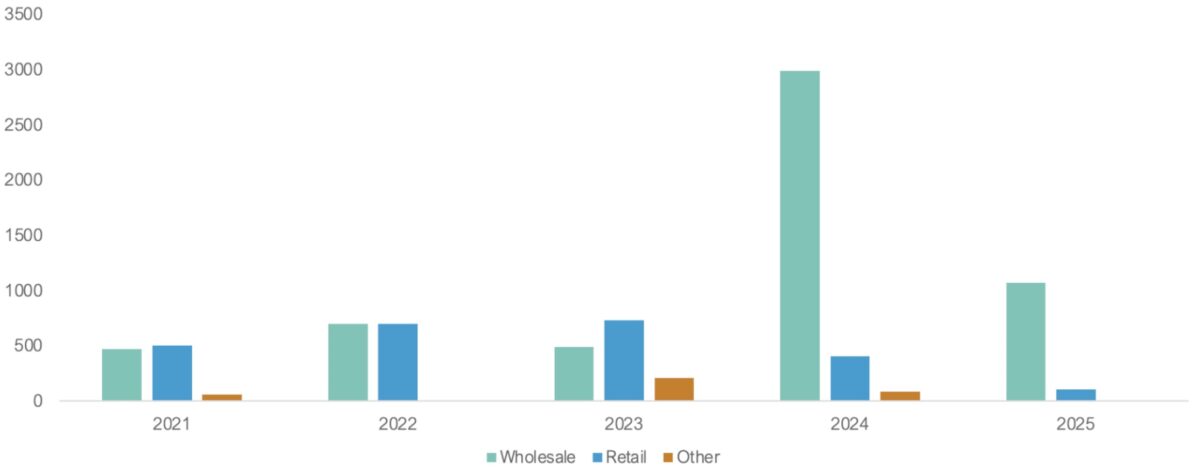

in the last couple of years, the wholesale PPA market has grown and the retail PPA market has slowed

Figure 4: PPAs by Deal Type (MW), 2021 – 2025

Screenshot

Screenshot

The retail PPA market and CIS have become inter-twined: the health of the retail PPA market relies in part on projects reaching financial close via the CIS to create new supply.

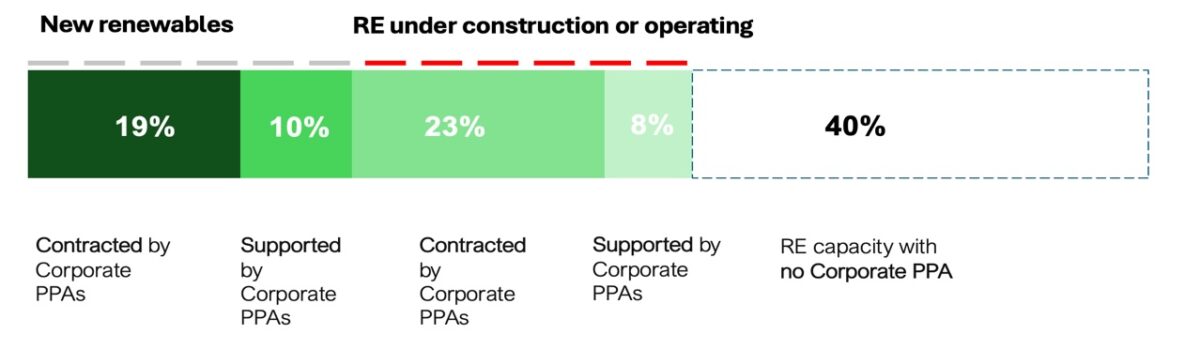

Looking at Corporate PPAs across a longer time-period, around 60 of the renewables project capacity has involved a PPA at some point. Corporate PPAs have enabled just under 30 per cent of the renewable energy capacity built since 2017 before financial close, and just over 30 per cent during construction or operating phase.

Figure 5: Renewable Energy Capacity and Corporate PPAs, 2017 – 2025

Note: Corporate PPAs typically contract for only some of the capacity of a renewable energy project.

‘Contracted’ = the portion of RE capacity directly contracted with a Corporate PPA

’Supported’ = the total size of the RE capacity of projects in which a Corporate PPA has been negotiated e.g. a 50MW PPA for a 100MW project counts as 50MW in the ‘contracted’ category and 100MW in the ‘supported’ category

Source: The renewable energy capacity that has reached ‘financial close’ since 2017 is sourced from the Clean Energy Council. The data on PPAs is from the BRC-A’s agreement database. The database includes only publicly available information on PPAs and sometimes requires estimates on capacity based on available information – it should be considered approximate.

All of which is to say Corporate PPAs play a significant role but they are very unlikely in and of themselves to fill the offtaker gap.

Policy implications

If market participants are correct in saying that the CIS has not led to prices that are sufficient to enable projects to reach financial close, change is required if the 2030 targets are to be achieved.

What are the options?

Option 1 would be to return to a standard CfD in the government auctions. That doesn’t appear to be on the agenda, especially as the NEM review authors have been critical of these auctions.

Option 2 is to make adjustments to the CIS to enable solar and wind projects to reach financial closure. If the CIS awards can offer better pricing and certainty than it appears they are currently delivering, more projects can reach financial closure. Once that has occurred, we are likely to see a virtuous circle formed with a pick-up in the retailer PPA market and tier-2 retailer activity feeding back into demand for more renewable energy.

Option 3 is to introduce a mechanism that gets the tier 1 retailers into the market for renewable PPAs – either through an incentive (e.g. carbon price) or a coal closure mechanism of some type. If the tier-1 retailers continue to stay out of the market, the CIS will have to do more or the government will have to explore other instruments.

There has been a lot of focus on the ‘tenure gap’ – the gap in the volume of buyers who will sign PPAs beyond 7-years to longer-terms for renewable energy projects.

Whilst it is true most corporate PPA buyers prefer short-terms (the exception are very large buyers seeking to use scale and tenure for low-prices), it is also true that most of these buyers also prefer to contract once a project has reached financial close.

A standardised contract of the type being proposed by the NEM review for years 8+ of a renewable project can be expected to streamline contracting, but the implicit assumption that the market will fill the gap for years 1 – 7 does not reflect what is currently occurring.

The most important gap now is not the tenure gap – it’s the offtaker gap and this needs to the focus of policy-makers to accelerate the build-out of the solar and wind farms required to achieve Australia’s targets.

Chris Briggs is a Research Principal in the Energy Futures team at the ISF. Chris has over 20 years of experience in policy, research and advocacy, working in Federal, State and City Government, the non-government and university sectors.