FRAC Dunkerque / Lacaton & Vassal. Image © Philippe Ruault

FRAC Dunkerque / Lacaton & Vassal. Image © Philippe Ruault

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1035638/the-architecture-of-restraint-when-choosing-not-to-build-becomes-design

In a world facing ecological exhaustion and spatial saturation, the act of building has come to represent both creation and consumption. For decades, architectural progress was measured by the new: new materials, new technologies, new monuments of ambition. Yet today, the discipline is increasingly shaped by another form of intelligence, one that values what already exists. Architects are learning that doing less can mean designing more, and this shift marks the emergence of what might be called an architecture of restraint: a practice defined by care, maintenance, and the deliberate choice not to build.

The principle recognizes that the most sustainable building is often the one that already stands, and that transformation can occur through preservation, repair, or even absence. Choosing not to build becomes a political and creative act, a response to the material limits of the planet and to the ethical limits of endless growth. That Architecture moves beyond the production of new forms to embrace continuity, extending the life of structures, materials, and memories that already inhabit the world.

This shift also challenges how we define architectural authorship and progress. Instead of equating innovation with novelty, it invites architects to engage with what is already there; to read the city as a palimpsest of histories, resources, and social relations. The act of building less becomes a question of judgment rather than capability, of knowing when to intervene and when to step back. In this space of restraint, architecture reclaims its critical agency not as the art of making, but as the discipline of making through less.

Related Article Deconstruct, Do Not Demolish: The Practice of Reuse of Materials in Architecture Building Less, Designing More

For much of the twentieth century, modern architecture equated progress with construction. Cities became laboratories for growth, and demolition was seen as a necessary step toward renewal. The rhetoric of “starting fresh” shaped postwar reconstruction, industrial expansion, and late-modernist urban planning. Yet this logic — of erasing to rebuild — has come under increasing scrutiny. Demolition disperses the carbon already stored in structures and triggers new emissions through replacement materials; it also generates large volumes of waste that are difficult to reinsert into productive cycles. Beyond environmental impact, it breaks social continuities: tenants are displaced, everyday networks are interrupted, and the memory embedded in the city is lost.

In contrast, architects such as Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal have grounded their work in the principle “never demolish, never remove, never replace”. Instead of treating the existing as an obstacle, they approach it as a starting point. At the Grand Parc renewal in Bordeaux, they retained postwar housing blocks and worked with their structural rhythm to graft winter gardens and generous balconies onto the facades, improving thermal performance and expanding domestic space without evacuating residents. Interior layouts were reconfigured with light-touch operations, bringing daylight deeper into the plan and allowing flexible occupation over time.

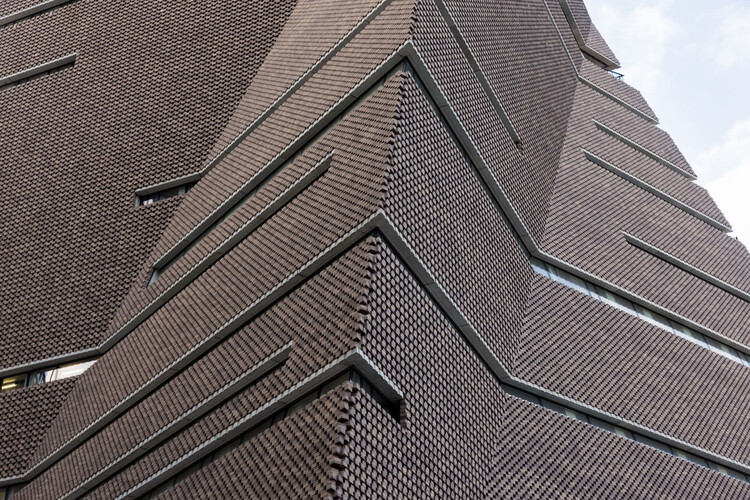

This approach is consistent across other works by the studio. At the Tour Bois-le-Prêtre, developed with Frédéric Druot, the team refused demolition proposals and instead enlarged the building envelope with prefabricated extensions, creating new rooms, loggias, and winter gardens for each apartment while upgrading services and insulation. The reuse of the structural frame preserved the building’s embodied resources and avoided the disruption of relocation. At the FRAC Nord–Pas de Calais, they maintained the vast hall of a former shipyard and added a simple, translucent volume alongside it, allowing the existing industrial space to remain active for exhibitions and public programs while the new volume provided controlled environmental conditions. But even when building from scratch, as in the School of Architecture in Nantes, the strategy is similar — designing a generous, open structure with intermediate spaces that can be occupied in multiple ways, minimizing fixed partitions and maximizing the capacity for future change, they run a consistent method: identify what works, reinforce the structure that holds value, and add only what is necessary to unlock new use.

FRAC Dunkerque / Lacaton & Vassal. Image © Philippe Ruault

FRAC Dunkerque / Lacaton & Vassal. Image © Philippe Ruault

A similar strategy can be found in the work of Rotor Deconstruction. Founded as a spin-off of the Brussels-based architecture collective Rotor, the initiative specializes in the careful dismantling and redistribution of building components. Rather than treating demolition as an endpoint, they view it as the beginning of a new material cycle. By cataloguing, cleaning, and reselling salvaged elements — from façade panels to door handles — Rotor creates a secondary market that challenges the linear logic of construction. Their operations are both logistical and cultural as they reveal the hidden labor embedded in materials and demonstrate that reuse can be systematic, not marginal. In doing so, they redefine what it means to design, shifting the architect’s role from maker to mediator, from producer of new objects to curator of existing ones.

Nantes School of Architecture / Lacaton & Vassal. Image Courtesy of Lacaton & Vassal

Nantes School of Architecture / Lacaton & Vassal. Image Courtesy of Lacaton & Vassal

Taken together, these projects clarify why transformation has become a credible alternative to replacement. By keeping primary frames, foundations, and circulation cores, they shorten construction time, reduce material throughput, and preserve the social life of a place. What was once seen as a limitation — the constraint of an existing structure — becomes a source of invention. In this model, authorship shifts from imposition to calibration. The designer listens to the building’s geometry, traces of occupation, and structural logic; the intervention emerges from those conditions rather than against them.

Design Through Absence

Restraint does not mean passivity. It requires precision, judgment, and imagination, the ability to intervene only where necessary and to design with minimal means. Few projects embody this more eloquently than David Chipperfield’s restoration of the Neues Museum in Berlin.

He inherited a ruin. Severely damaged during World War II and left untouched for more than half a century, the building existed as both a cultural void and a monument to loss. Chipperfield’s intervention, developed with conservation specialist Julian Harrap, did not aim to restore the museum to its pre-war appearance nor to disguise its destruction. Instead, it sought to stabilize and complete what remained, preserving the building’s historical layers as tangible records of time. New elements — staircases, columns, and wall surfaces — were added only where structurally essential, using materials such as pale brick, concrete, and oak that quietly differentiate themselves from the original fabric. The new never imitates the old, and the old is never idealized; both coexist in a carefully balanced composition of absence and presence.

New Museum Island Gallery, David Chipperfield. Image © James-Simon-Galerie. © Ute Zscharnt

New Museum Island Gallery, David Chipperfield. Image © James-Simon-Galerie. © Ute Zscharnt

This understanding of design as measured intervention also defines Sala Beckett, a project by Flores & Prats that transformed a decaying cooperative building into a theatre and cultural laboratory. Rather than stripping the structure back to a neutral shell, the architects preserved the residue of previous lives: faded frescoes, cracked tiles, remnants of stage sets. The new spatial organization unfolds around these traces, treating them as actors in the ongoing narrative of the building. Walls were patched rather than repainted, doors were adjusted instead of replaced, and new partitions were built as reversible frameworks. The building’s imperfections were not concealed but illuminated, revealing how memory can coexist with use, and how fragility can become a form of strength — maximum effect through minimum action.

Sala Beckett / Flores & Prats. Image © Jose Hevia

Sala Beckett / Flores & Prats. Image © Jose Hevia

Both projects articulate a way of working defined not by addition, but by calibration. They resist the modernist impulse to erase and remake, replacing it with a patient search for continuity. Their power lies not in visual spectacle but in what remains unsaid — the voids, the silences, the unaltered walls that hold the weight of history. This economy of gesture transforms limitation into aesthetic intelligence. The less that is added, the more the existing fabric speaks. When seen together, these approaches reveal that absence can be as expressive as form. It is an architecture of patience and empathy, in which restraint becomes the medium through which meaning is constructed. In a time when excess has exhausted its possibilities, these practices show that doing less — and doing it well — may be the most radical act of all.

The Aesthetics of the Incomplete

Restraint also redefines aesthetics. The architecture of the twentieth century often pursued completeness. In contrast, many contemporary works find expression in incompleteness, embracing the unfinished, the layered, and the imperfect. This sensibility acknowledges that buildings, like cities, are never static; they exist in continuous negotiation with time, decay, and use.

Sala Beckett / Flores & Prats. Image © Jose Hevia

Sala Beckett / Flores & Prats. Image © Jose Hevia

Peter Zumthor’s Kolumba Museum captures this idea with remarkable clarity. Built upon the ruins of a bombed Gothic church, the project preserves the remains not as relics to be protected behind glass, but as integral elements of the new architecture. Zumthor enveloped the ruins with a porous brick structure, its perforated façade filtering light and air while allowing the old masonry to remain visible. The material continuity between the old and the new, the handmade bricks, the muted tones, the tactile surfaces, produces a sense of quiet dialogue. Inside, visitors move between fragments of walls and contemporary volumes, between shadow and light, between what endures and what has been lost. The museum does not resolve history; it holds it open. Its beauty lies precisely in that tension; in the way fragility is given dignity without being disguised.

Kolumba Museum / Peter Zumthor. Image © Jose Fernando Vazquez

Kolumba Museum / Peter Zumthor. Image © Jose Fernando Vazquez

But long before Zumthor, Sverre Fehn articulated a similar approach in his Hedmark Museum. Built among the ruins of a medieval fortress, Fehn inserted a sequence of concrete and timber walkways that hover delicately above the archaeological remains. The intervention does not reconstruct what was lost, nor does it mimic the old masonry. Instead, it frames it, creating a space of encounter between epochs. Fehn’s architecture of suspension anticipated many of the questions that contemporary architects continue to explore today: How can we build within what already exists without consuming it? How can the new give voice to the old?

Hedmark Museum, Sverre Fehn. Image © Peter Guthrie, via Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Hedmark Museum, Sverre Fehn. Image © Peter Guthrie, via Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

A similar sensibility shapes Herzog & de Meuron’s Tate Modern. The architects’ decision to convert the Bankside Power Station into an art museum was not merely functional reuse, but an acknowledgement of the structure’s latent character. The turbine hall, left largely intact, became both a public space and a spatial manifesto — a cathedral of industrial memory. By maintaining the monumental brick shell and reinterpreting it with new insertions, Herzog & de Meuron revealed how the traces of labor, soot, and steel could form the aesthetic foundation of contemporary culture. The later addition of the Switch House tower in 2016 extended this narrative, continuing the dialogue between utility and imagination. The power of the Tate Modern lies in its refusal to sanitize the past; it celebrates the endurance of material and the adaptability of form.

Modern Switch House / Herzog & de Meuron. Image © Iwan Baan

Modern Switch House / Herzog & de Meuron. Image © Iwan Baan

Together, these works demonstrate that the incomplete is not an error to be corrected but a condition to be understood. By refusing total restoration or aesthetic closure, they allow buildings to express the passage of time as part of their identity. The cracks, marks, and scars are not erased but inscribed into the experience of space. In the Kolumba, the fragments of a church become part of a contemporary museum; in the Tate Modern, an obsolete factory becomes a civic living room; in the Hedmark Museum, ruins become structure, and structure becomes memory. By embracing imperfection, architecture finds a new form of beauty, one that acknowledges the unfinished nature of every place and the shared responsibility of keeping it alive.

The Ethics of Non-Building

Behind this aesthetic lies an ethical position. To choose not to build is to resist the economic systems that equate progress with development. It questions the assumption that architectural value is measured in square meters or in the spectacle of new form, challenging a profession long dependent on growth-based models. In an era when construction itself contributes significantly to global carbon emissions, this act of refusal becomes a statement that less can, in fact, sustain more.

Hedmark Museum, Sverre Fehn. Image © Peter Guthrie, via Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Hedmark Museum, Sverre Fehn. Image © Peter Guthrie, via Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The future of architecture may depend less on expansion than on the capacity to renew what already exists. Drawing on Jaime Lerner’s belief that “the future of architecture lies not in building new cities, but in updating those that already exist,” Romullo Baratto in Back to the Future: Why Refurbishing Matters, written for ArchDaily’s book, frames reuse as an act of intelligence; a form of progress grounded in continuity rather than rupture. Within this perspective, the work of architecture is not to add more, but to understand how the existing can be transformed, extended, and cared for.

Keller Easterling, in her essay Subtraction, argues that not building can constitute one of the most potent spatial interventions available today. For Easterling, subtraction is not simply the removal of matter but an active reconfiguration of existing conditions — a recalibration of the urban environment through editing rather than expansion. Demolition, abandonment, or vacancy, she notes, are not endpoints but phases that can be strategically managed to open new forms of occupation and value. By treating empty lots, residual infrastructures, or obsolete buildings as latent resources, architects can work within what she calls the space of the existing, turning stillness into opportunity. Subtraction, in this sense, is designed through intelligence rather than accumulation.

Alte Pinakothek. Image © Philipp Heer

Alte Pinakothek. Image © Philipp Heer

This idea resonates with Jonathan Hill’s argument in Immaterial Architecture, where he expands the discipline beyond the physical object to include the invisible labor of use, adaptation, and maintenance. Hill insists that architecture does not end when construction stops; it continues through the acts that sustain it (cleaning, repairing, modifying, inhabiting). Every user becomes an architect, and every adjustment, however small, contributes to the life of the built environment. Both Easterling and Hill redefine design as an act of care and not a heroic gesture of form-making; a distributed process of stewardship that keeps the city alive. This is not about nostalgia or conservation, but about acknowledging interdependence between buildings and their users, between construction and ecology.

Building less ultimately calls for a reimagining of architectural agency. It challenges professionals to design not only structures but also infrastructures of care. It invites architects to see the existing city as a field of potential, where every wall, street, or fragment can be reactivated rather than replaced. The discipline’s future may depend less on new monuments and more on invisible gestures. In this paradigm, design becomes a form of editing, an act of choosing what to keep, what to transform, and what to leave untouched. The measure of creativity lies not in expansion but in restraint, not in quantity but in consequence. To build less, in the end, is not to design less; it is to design with greater precision, responsibility, and imagination.

Hastings Pier. Image © Alex de Rijke

Hastings Pier. Image © Alex de Rijke

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Building Less: Rethink, Reuse, Renovate, Repurpose, proudly presented by Schindler Group.

Repurposing sits at the nexus of sustainability and innovation — two values central to the Schindler Group. By championing this topic, we aim to encourage dialogue around the benefits of reusing the existing. We believe that preserving existing structures is one of the many ingredients to a more sustainable city. This commitment aligns with our net zero by 2040 ambitions and our corporate purpose of enhancing quality of life in urban environments.

Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

Transformation of 530 dwellings / Lacaton & Vassal + Frédéric Druot + Christophe Hutin architecture. Image © Philippe Ruault

Transformation of 530 dwellings / Lacaton & Vassal + Frédéric Druot + Christophe Hutin architecture. Image © Philippe Ruault