Duisburg-Nord public park. Photography & Concept. Image © Erieta Attali

Duisburg-Nord public park. Photography & Concept. Image © Erieta Attali

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1032522/a-different-type-of-rurality-designs-for-post-industrial-heritage-transformation

Across the rural terrains of North America and Western Europe, traces of past industry remain embedded in the land: mills rusting in meadows, smokestacks punctuating quiet townscapes, the skeletons of once-thriving economies. For decades, these sites have signified decline through the remnants of an extractive era that has shaped the environment and local identity. The challenges of remediation often encompass technical, environmental, and cultural aspects that require creativity, precision, and sensitivity.

Post-industrial rural landscapes are not empty. They are spatially and culturally layered: materially complex, culturally charged, and ecologically wounded. They are also fertile ground for new forms of design, ones rooted in recovery rather than erasure. In these contexts, spatial strategies can support regeneration in multiple forms, including honoring heritage, restoring ecosystems, fostering community life, and adapting forgotten structures to new futures.

This is where landscape architecture and spatial design play a critical role. This essay examines four overlapping design approaches that reinterpret rural post-industrial sites: heritage preservation, ecological remediation, participatory cultural programming, and adaptive reuse. Rather than viewing these landscapes as liabilities, each strategy sees them as shared assets that are capable of reconnecting people to place, memory to soil, and design to care.

Related Article Transforming Industrial Heritage: Design Strategies for Creating a New Atmosphere in Cultural Spaces Heritage Preservation: Industrial Ruins as Cultural Assets

In many rural areas shaped by industry, the remnants of production remain present and visible. Grain elevators, kilns, and steel frameworks still define skylines, even as the systems that sustained them have faded. Preserving these structures involves more than stabilizing materials; it means recognizing them as part of the cultural and spatial fabric.

Leszczynski Antoniny Manor Intervention / NA NO WO architekci. Image © Maciej Lulko

Leszczynski Antoniny Manor Intervention / NA NO WO architekci. Image © Maciej Lulko

These remnants hold knowledge. They reveal how communities organized space, how materials were used, and how labor shaped daily life. Their forms, weathered and monumental, have gained a quiet dignity. Rather than being seen as obsolete, they can be reframed as anchors of memory and continuity.

Designers working with industrial heritage often face the challenge of balancing preservation with adaptation. Some projects leave buildings in a state of controlled decay, allowing the passage of time to remain visible. Others weave new uses into old frameworks, transforming chimneys into observation towers or repurposing loading bays as gathering spaces. These interventions do not aim to replicate the past, but to frame it as part of an evolving story.

The Levitt Pavilion / WRT – Wallace Roberts & Todd The Levitt Pavilion / WRT – Wallace Roberts & Todd. Image © Paul Warchol PhotographyZollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex / Fritz Schupp and Martin Kremmer (Photographed by Erieta Attali and Philipp Valente)

The Levitt Pavilion / WRT – Wallace Roberts & Todd. Image © Paul Warchol PhotographyZollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex / Fritz Schupp and Martin Kremmer (Photographed by Erieta Attali and Philipp Valente) Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex in Essen. Photography & Concept . Image © Erieta AttaliOld Mill Conversion into Cultural Centre / studio nada

Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex in Essen. Photography & Concept . Image © Erieta AttaliOld Mill Conversion into Cultural Centre / studio nada old Mill Conversion into Cultural Centre / studio nada. Image © Todor TodorovEcological Remediation: Restoring Damaged Landscapes

old Mill Conversion into Cultural Centre / studio nada. Image © Todor TodorovEcological Remediation: Restoring Damaged Landscapes

Industrial activity leaves behind more than structures. Contaminated soils, disrupted water systems, and degraded habitats often define the post-industrial landscape, even when these damages are hidden from view. Ecological remediation differs from conventional approaches that prioritize removal or containment. It engages living systems, such as plants, microbes, soils, and hydrology, as active participants in the recovery process. Through techniques such as phytoremediation and constructed wetlands, these interventions support healing over time.

Solana Ulcinj, Montenegro.. Image © Bart Lootsma

Solana Ulcinj, Montenegro.. Image © Bart Lootsma

In many rural sites, ecological repair becomes the primary design structure. Paths may follow water channels, planting patterns may reflect zones of contamination, and seasonal change becomes part of the spatial experience. Rather than erasing damage, these designs make it visible and legible, allowing recovery to unfold in public view.

These landscapes require long-term commitment. Remediation is not immediate, and success depends on ongoing care. Yet when treated with patience and creativity, these sites can become powerful demonstrations of resilience and renewal.

ArtsQuest Center at SteelStacks / Spillman Farmer Architects ArtsQuest Center at SteelStacks / Spillman Farmer Architects. Image Courtesy of spillman farmer architectsMontenegro Pavilion at the 2016 Venice Biennale / Bart Lootsma and Katharina Weinberger

ArtsQuest Center at SteelStacks / Spillman Farmer Architects. Image Courtesy of spillman farmer architectsMontenegro Pavilion at the 2016 Venice Biennale / Bart Lootsma and Katharina Weinberger  Solana Ulcinj, Montenegro.. Image © Bart LootsmaDuisburg-Nord Public Park / Latz + Partner (Photographed by Erieta Attali and Philipp Valente)

Solana Ulcinj, Montenegro.. Image © Bart LootsmaDuisburg-Nord Public Park / Latz + Partner (Photographed by Erieta Attali and Philipp Valente) Duisburg-Nord public park. Photography & Concept. Image © Erieta AttaliKnepp Estate Rewilding Efforts in West Sussex

Duisburg-Nord public park. Photography & Concept. Image © Erieta AttaliKnepp Estate Rewilding Efforts in West Sussex Knepp Estate Rewilding, West Sussex.. Image © Mark Wordy via Flickr under CC BY 2.0Participatory Cultural Programming: The Role of Placemaking

Knepp Estate Rewilding, West Sussex.. Image © Mark Wordy via Flickr under CC BY 2.0Participatory Cultural Programming: The Role of Placemaking

When industry leaves, it often takes with it more than jobs. It removes places of gathering, moments of celebration, and shared rituals that once defined public life. In many rural areas, cultural infrastructure disappears along with economic systems. As designers return to these sites, programming becomes a central question: how can space support social life once again?

Cultural programming in post-industrial contexts begins with listening. Rather than arriving with a fixed brief, design teams must collaborate with local communities to understand traditions, informal uses, and collective needs. Through consultation and co-creation, spaces begin to emerge that reflect local identity and aspirations.

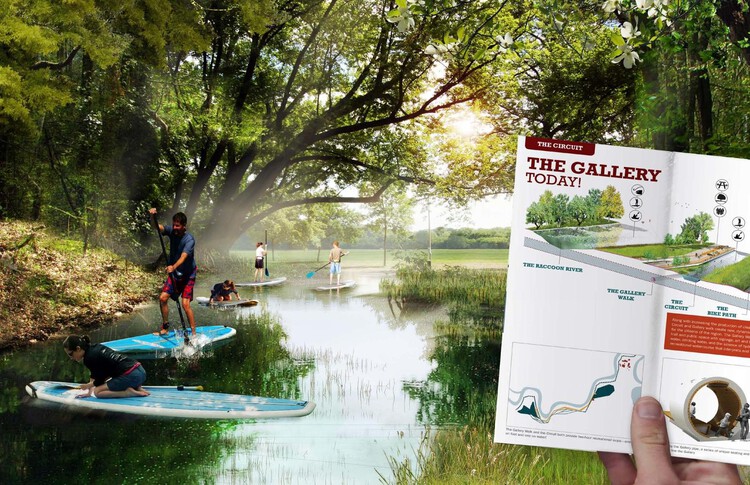

Water Works Park / Sasaki Associates. Image Courtesy of Sasaki Associates

Water Works Park / Sasaki Associates. Image Courtesy of Sasaki Associates

These interventions are often modest. Pavilions, stages, and covered gathering areas become the spatial scaffolding for festivals, markets, performances, and ceremonies. Industrial clearings, once defined by machinery, are repurposed for people. The result is not simply activity, but ownership. Importantly, cultural programming is not about importing external ideas; it is about fostering local creativity and enabling what already exists to find expression in a new space.

High Trestle Trail Bridge / RDG Planning & Design High Trestle Trail Bridge / RDG Planning & Design. Image © IRIS22 ProductionsHallenhaus / Observatorium

High Trestle Trail Bridge / RDG Planning & Design. Image © IRIS22 ProductionsHallenhaus / Observatorium Hallenhaus / Observatorium. Image © Thomas MayerWater Works Park / Sasaki Associates

Hallenhaus / Observatorium. Image © Thomas MayerWater Works Park / Sasaki Associates Water Works Park / Sasaki Associates. Image Courtesy of Sasaki AssociatesAdaptive Reuse: Transforming Industrial Campuses

Water Works Park / Sasaki Associates. Image Courtesy of Sasaki AssociatesAdaptive Reuse: Transforming Industrial Campuses

Rural post-industrial buildings are often built with strength and purpose. Their large volumes, structural clarity, and durable materials offer opportunities for transformation. Adaptive reuse allows these spaces to support new functions, providing communities with much-needed resources while preserving the memory embedded in form.

Reuse in rural settings brings its own set of challenges. Projects often operate with limited funding, modest populations, and constrained infrastructure. Yet, these limitations can also serve as a guide to creativity. Buildings are repurposed incrementally, using local materials, volunteer labor, and phased construction. Design decisions are shaped by need, often prioritizing utility over grand gestures.

The Kamenice Brewery / OTA atelier. Image © Benedikt Markel

The Kamenice Brewery / OTA atelier. Image © Benedikt Markel

These spaces can support a range of uses, including community kitchens, artist studios, shared workshops, educational centers, and mixed-use facilities. By layering contemporary needs onto existing frameworks, reuse projects build continuity rather than rupture. The original structures are not erased, but reinterpreted. In this way, adaptive reuse becomes a form of design that values what already exists. It honors industrial heritage while cultivating new forms of life, meaning, and use.

The Kamenice Brewery / OTA atelier The Kamenice Brewery / OTA atelier. Image © Benedikt MarkelRegional Center of Industrial Heritage / Mihailo Timotijević & Miroslava Petrović Balubdžić

The Kamenice Brewery / OTA atelier. Image © Benedikt MarkelRegional Center of Industrial Heritage / Mihailo Timotijević & Miroslava Petrović Balubdžić Regional Center of Industrial Heritage / Mihailo Timotijević & Miroslava Petrović Balubdžić. Image © Ana KosticLeszczynski Antoniny Manor Intervention / NA NO WO architekci

Regional Center of Industrial Heritage / Mihailo Timotijević & Miroslava Petrović Balubdžić. Image © Ana KosticLeszczynski Antoniny Manor Intervention / NA NO WO architekci Leszczynski Antoniny Manor Intervention / NA NO WO architekci. Image © Maciej LulkoRenovation of a Mill and Hayloft for Residential use / Funcionable arquitectura

Leszczynski Antoniny Manor Intervention / NA NO WO architekci. Image © Maciej LulkoRenovation of a Mill and Hayloft for Residential use / Funcionable arquitectura Renovation of a Mill and Hayloft for Residential use / Funcionable arquitectura. Image © Imagen SubliminalToward a Rural Ethos of Design

Renovation of a Mill and Hayloft for Residential use / Funcionable arquitectura. Image © Imagen SubliminalToward a Rural Ethos of Design

Design in post-industrial rural contexts requires a different pace and perspective. These landscapes are shaped by slow processes of erosion, repair, memory, and demand design strategies that work in harmony with these rhythms. They are not blank slates, but layered terrains where cultural, ecological, and material histories converge.

To design in this context is to accept limits. It means working with what is already present, responding to what the land offers, and building trust with the communities who remain. Rather than imposing new futures, the designer’s role becomes one of stewardship, creating conditions for regeneration to unfold over time.

Hasanpaşa Gasworks Park and Museum Complex / İTÜ & DS Architecture. Image © Cemel-Emden

Hasanpaşa Gasworks Park and Museum Complex / İTÜ & DS Architecture. Image © Cemel-Emden

Finally, what matters in these projects is not scale or spectacle, but meaning. A reused factory, a rewilded clearing, and a seasonal gathering transform into acts of care that shape how people live in and with their place. The industrial past is not forgotten, but reframed as part of a shared future. In this way, post-industrial rural sites carry enormous potential. When approached with patience and humility, they embody more than remnants of decline. They become living commons, where memory, ecology, and culture can take root together.

Chevron Oil Refinery, Pascagoula, Mississippi . Image © Daily Overview

Chevron Oil Refinery, Pascagoula, Mississippi . Image © Daily Overview

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Regenerative Design & Rural Ecologies. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

Related Article Transforming Industrial Heritage: Design Strategies for Creating a New Atmosphere in Cultural Spaces