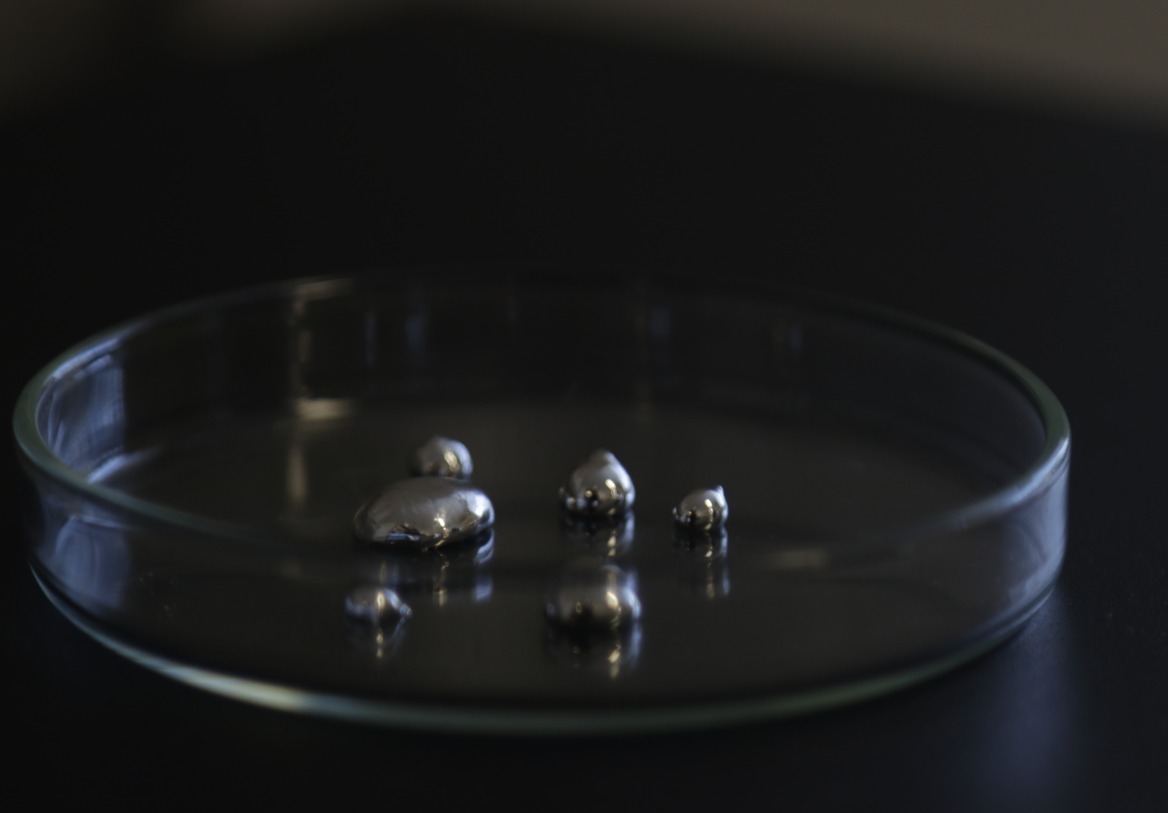

Gallium in a petri dish. Image credit: Philip Ritchie. Image supplied by the University of Sydney.

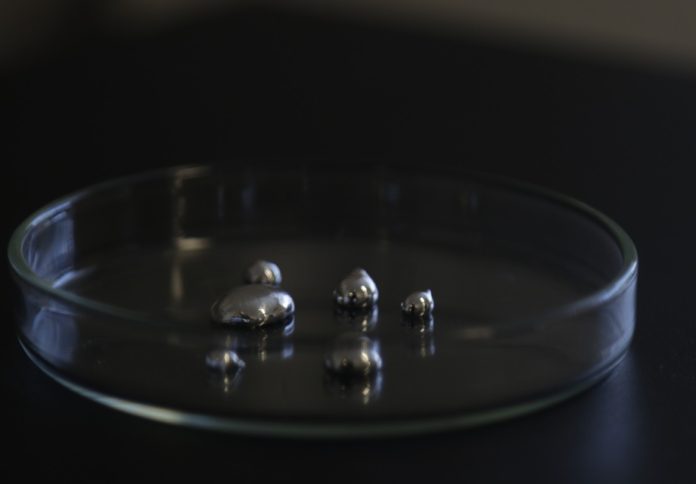

Gallium in a petri dish. Image credit: Philip Ritchie. Image supplied by the University of Sydney.

Scientists at the University of Sydney have captured rare footage of platinum crystals growing inside liquid metal, using advanced X-ray computed tomography to observe a process normally hidden from view.

The research, published in Nature Communications, demonstrates how liquid metal–grown crystals could support emerging technologies, including hydrogen production from water and future quantum computing applications.

According to the University of Sydney, the team used the crystals to develop an electrode capable of efficiently producing hydrogen.

Professor Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh, who led the study from the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, said the opacity and density of elements like gallium have long made it difficult to observe crystal formation.

“Witnessing the formation of crystals inside liquid metals like Gallium is a challenging task,” he said. “It was a really special moment to be able to develop a method to do this.”

Using X-ray computed tomography – equipment commonly used in medical imaging – the researchers produced 3D images showing rod-like, frost-shaped crystals forming over minutes and hours inside the liquid metal.

“To see how liquid metals can be harnessed to shape the future of smart materials and identify those that play important roles in energy sources, we need to understand their metallic and chemical properties, inside and out,” Professor Kalantar-Zadeh said. “With X-ray computed tomography, we can now truly see what we are working with.”

The study involved dissolving platinum beads in gallium or gallium-indium liquid metal at 500°C, then cooling the mixture to spark crystal growth. PhD student and co-author Ms Moonika Widjajana said the tomography technique allowed researchers to overcome a longstanding visibility barrier.

“This study illustrated how X-ray computed tomography can overcome the challenge of observing crystal growth within liquid metal,” she said.

The University of Sydney noted that while current techniques provide only low-resolution images, continued advances may soon offer even deeper insight into how metallic crystals form.

Read the research here: https://doi.org/10/1038/s41467-025-66249-y