SOME calf abortions linked to the cattle disease trichomoniasis appear to be the result of inherited infection, with empty and dry cows under suspicion of harbouring the disease, according to the Australian Agricultural Co’s chief scientist.

Dr Matt Kelly

Dr Matt Kelly said a three-year, 4500 bull-testing study found a 12pc heritability factor for the incurable venereal disease spread by infected bulls through northern Australian herds.

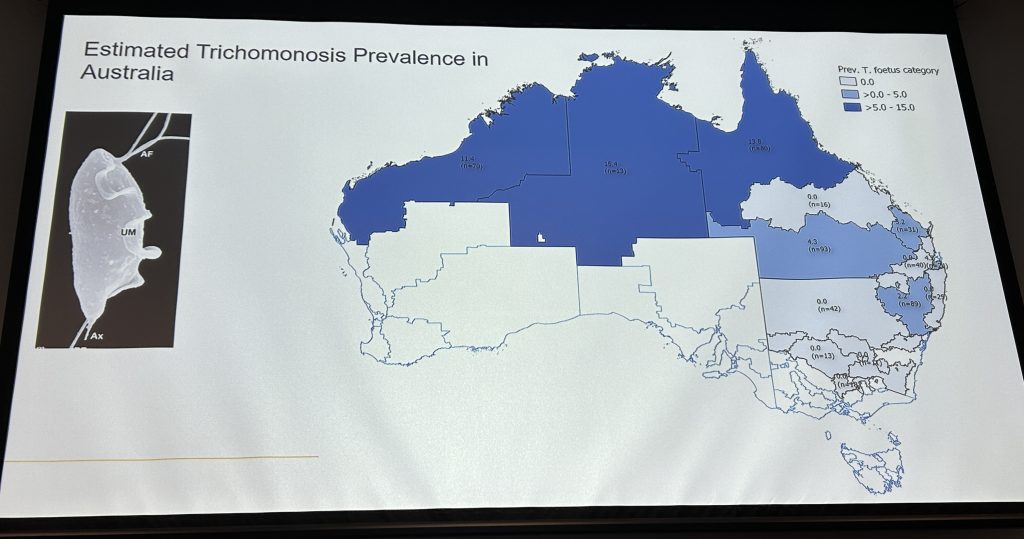

Trichomoniasis (sometimes called trich) is a significant sexually transmitted disease causing embryonic death shortly after conception. In North Australian beef herds, losses from confirmed pregnancy to weaning are typically between 5pc and 15pc and are estimated to cost the industry between $60 million and $100 million a year.

Dr Kelly told last week’s Trop Ag conference that trich disease analysis needs to look at females. “Does it carry in the cows, in particular in maiden herds?” he told a Trop Ag session on Friday in Brisbane. “We need to understand what we are doing with our dry cows or our empty cows, because they have females that are potentially carrying it for a period there and keeping the epidemic disease floating around.”

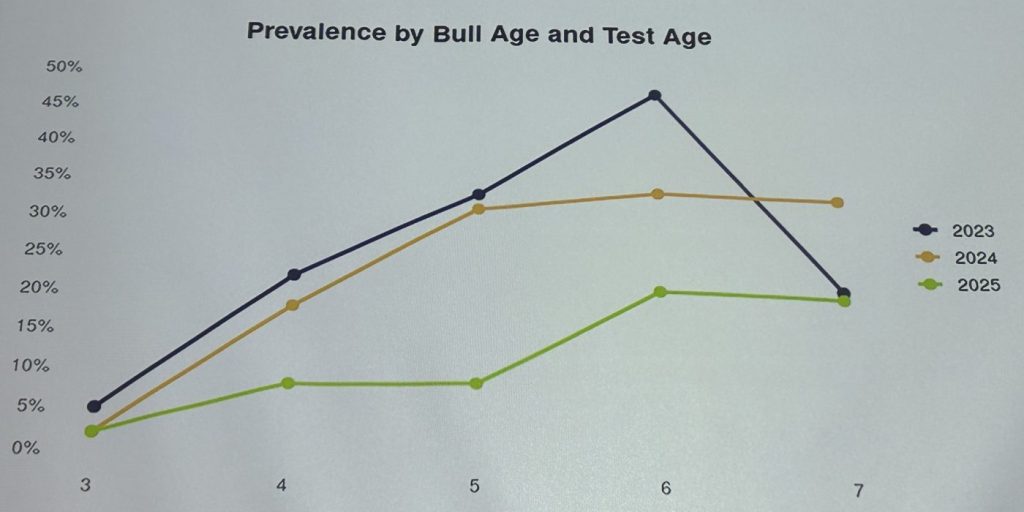

Among the other findings he reported were: “We had really strong patterns with age. Young bulls tend to hold to themselves, so they don’t get access to other infected bulls. So actually that’s very handy for very young bulls, but (contact) goes up gradually and (infection) tends to plateau.

“So that’s what led us to start thinking about genetics. There are still some older bulls that aren’t getting infected. It’s hard to believe they’re not coming in contact with other bulls that carry it.

“So that got us thinking why all bulls are not infected, or why does that pattern happen? Which led us to thinking – is there a genetic component?”

Dr Kelly admitted it is a geneticist at heart . “Give me genotypes and a trait and we’ll have a look at it. That’s a flippant way of saying it, but if there’s a trait or a genetic control it’s one thing we can put in the armament to work – along with test-and-cull and the vaccine – to bring the prevalence down.

“The way we actually built the trait was because we have lots of animals with no prevalence. We had to make sure that each bull included in the analysis had been in the presence of another positive bull.

“So we ended with a data set out of all those 4000 tests of 3000 genotype bulls. And the end of the story is that it is a heritable trait of 12pc. So it is heritable, but the question is – what is the actual trait? It could just be a function of libido – it probably isn’t – or is it immune response? We have to understand that because we don’t want to be tracking a lot of low-libido bulls in northern Australia.”

Systematic screening of AA Co herds

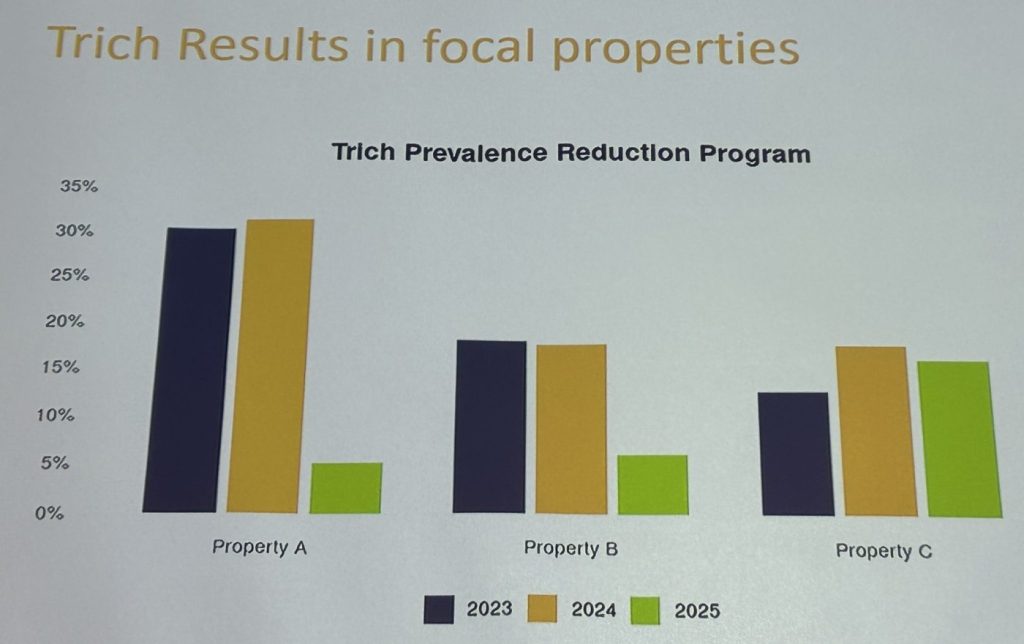

His findings followed a systemic screening that found herds with up to 30pc infection on ten AA Co properties.

Dr Kelly explained: “It is potentially a big problem for us. Trich it causes abortions in cows. There is no current treatment or vaccine. The only thing we can do is test all of our bulls and cull – which is not very nice for the bulls.”

“For the first stage of this project we went to ten of our properties and tested a sub-sample of bulls to see what they have, and whether it was actually a problem. We had prevalences ranging from 30pc down to zero.”

The low-incidence properties were the AA Co stud properties, he said. “There is some good news stories, some logic there. They are our studs where our breeding is tightly managed, they tend to have young teams, they also tend to have very controlled joining groups and a lot more attention. We control neighbours’ bulls and things like that.

“The set up intentionally is biosecurity-focussed because those bulls go everywhere,” he said, adding: “But not so good for our extensive properties.

“So the first step of the project: understand the problems. And then we sat down with our veterinary advisory team and asked which properties are we going to try and tackle this at, because it is a big problem. It involves a lot of testing . Some of our properties have between 1500 bulls down to 600 bulls. How do we make sure we go and do a proper job?”

He continued: “What we ended up doing was choosing three properties: one that had a low-prevalence, because it was high-value and we felt that we could control and had a good handle on bull control there. We knew what neighbours we had. We thought we had control there.

“And then we chose two of the high-prevalence properties because we can’t keep tolerating that. Let’s see if we can make a big difference on those properties.”

He explained: “The next step involved testing every bull that came through the yards on the three sample properties, identifying any positives and culling those and replacing them with younger, non-infected bulls.

“So, it’s a big project. Each one of these samples takes a couple of minutes to collect. It’s a big logistical challenge because the labs aren’t any longer in Australia either. So you had to take the samples and keep them cool and then send them down to Brisbane or to down to Western Australia.

“And a little random fact here: people weren’t ready for this – we exhausted all the all the trich chemicals in this first year of the project.”

4500 bulls tested

The three year trial involved three properties and tested about 4500 bulls.

Dr Kelly continued: “So, the interesting thing – did it actually make any difference?

“At this time last year we were very sad. we had tested thousands of bulls and we had not made much difference in the prevalence. So I think this is a problem with endemic diseases in extensive environments and also with understanding the actual way that the test works. We needed to do repeated testing before we started to have an impact on the disease.

“So, (on two properties) we had big efforts of testing as many bulls as we could, We did even more thorough musters and more diligence, particularly in the second year, and we were able to reduce the prevalence in those two properties.

“Unfortunately (for the third property) we didn’t get as many bulls in and we had more problems with bull control. We needed to hold it … but we have plans to get in a bit harder and get in and make a difference next year.

“So, take home is – it’s not something you can take lightly, if you’re going to use a test-and-cull procedure.

“It absolutely demonstrated why it’s so important to try to get vaccine and other processes in place. We can do it, but it’s hard work.”

He concluded: “In summary test-and-cull can definitely reduce the prevalence of trich even in big, extensive properties . It really does require a really big focus on bull control and testing. There’s a lot of work that goes into this.”

About Bovine Trichomoniasis

Bovine Trichomoniasis (trich) is a sexually transmitted disease caused by the protozoan parasite Tritrichomonas foetus. The parasites can infect the genital tracts of cattle during mating. They can also be spread by contaminated equipment used for calving or AI, or if contaminated semen is used for AI.

Embryonic death usually occurs shortly after conception, in which case, the cow simply absorbs the dead embryo and comes back on heat.

It may therefore appear to an observer that an affected cow is simply having long cycles. If the affected embryo survives longer, abortion may occur, but usually before five months of gestation.

These early abortions may also remain undetected with the apparent problem diagnosed as herd infertility. In five to 10pc of cases, abortion does not occur and the foetus degenerates in the uterus which may then become filled with pus (pyometron).

In North Australian beef herds, losses from confirmed pregnancy to weaning are typically between 5 to 15pc and are estimated to cost the industry between $60 and $100 million a year. While not solely responsible, bovine trichomoniasis is thought to be contributing to this reproductive inefficiency.

Bulls serve as asymptomatic carriers, harbouring the parasite in their reproductive tract and passing it on to cows during breeding.

There is no approved, effective treatment or commercial vaccine for trichomonosis available in Australia. Vaccines used overseas do not prevent infection; but might help speed recovery.

Bulls display no overt clinical signs and can only be confirmed as carriers by way of a PCR test.

While vaccine development in Australia is ongoing, culling infected animals is currently the only viable option.

Meat & Livestock Australia supported his study. The AA Co team worked with the Centre for Animal Science, Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation and included Eliza Gray and Caiti Rosengren (AA Co), Dr Hannah Siddle (QAAFI), Prof Ala Tabor (QAAFI), Zhetao Zhang (QAAFI) and Dr James Copely (AA Co).